That’s the challenge for Hollywood. A real, major criminal investigation grinds away with more dull moments than the worst high school class you can remember. Agents and clerks of all stripes pour over old phone records, or old bank statements, or some form of ancient paperwork until they think their eyes may drop out of their head. Dull boxes of day-old pizza, strewn around the tables they hunch over for endless hours, seem interesting by comparison. And guys at a stakeout sit so long they swear their butts are going to turn into car upholstery.

That’s the challenge for Hollywood. A real, major criminal investigation grinds away with more dull moments than the worst high school class you can remember. Agents and clerks of all stripes pour over old phone records, or old bank statements, or some form of ancient paperwork until they think their eyes may drop out of their head. Dull boxes of day-old pizza, strewn around the tables they hunch over for endless hours, seem interesting by comparison. And guys at a stakeout sit so long they swear their butts are going to turn into car upholstery.

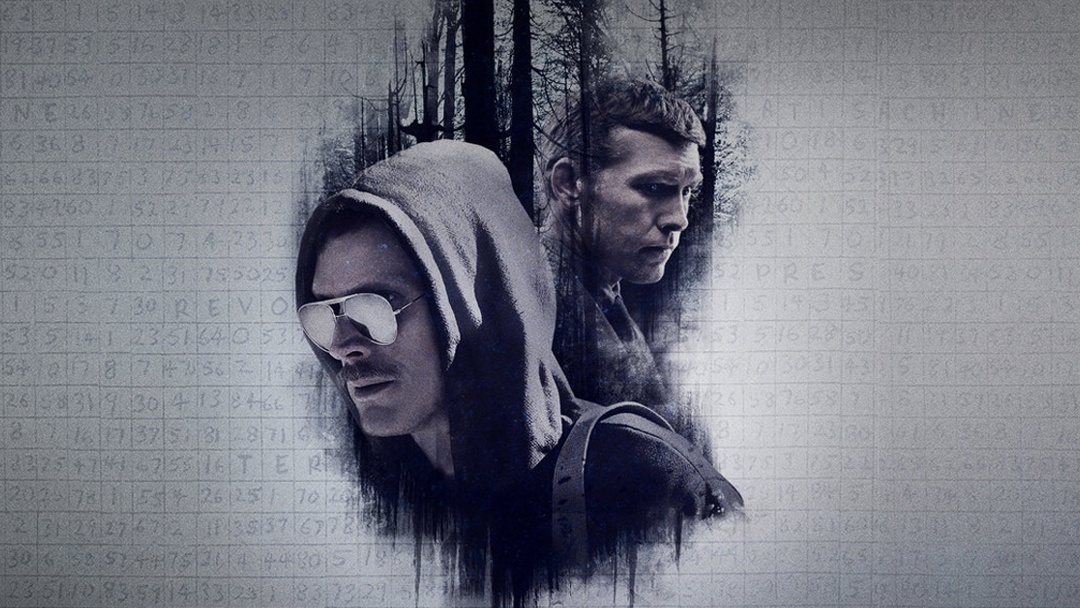

The point is that many mysteries are solved one grain of sand at a time, and television falls short as a medium to capture a process of slow sweat, not fast glamour. Thus don’t expect Discovery Channel’s miniseries on the manhunt to rope in the Unabomber to stick to the rails of the true story. Dozens of agents are collapsed into one–the audience gets its protagonist in agent James Fitzgerald–and lots of hokey personal angles are injected to spice up a technical story.

Even with those limitations, you should stream the series on Netflix anyway!

Mystery analysts will find two veins to mine deeply and richly as the episodes roll by.

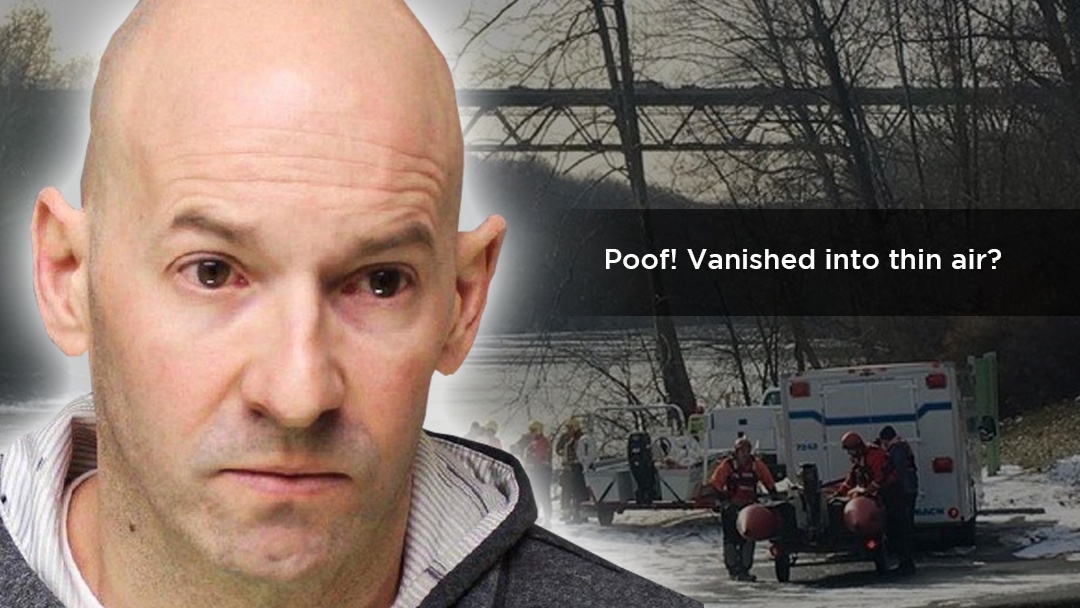

For one, the emergence of forensic linguistics as a powerful, intriguing tool to establish identities. In simplest form, we all have vast unconscious patterns in our communication, from spelling quirks to the regional use of words, to unusual vocabulary preferences, to the syntax and pattern and overall style with which we express ourselves. If I write a long article, even a long note, a rigorous analysis could well identify me as the author. The novel Primary Colors, made into the film starring John Travolta and Emma Thompson, was published anonymously, until academic linguist Don Foster pinned it on journalist Joe Klein, who finally “confessed.”

And second, the emergence of the broader field of “behavioral analysis” –a new world in which the psychologist’s report equals all the bagged chemical forensics–blooms throughout this series. After all, the Unabomber by definition would have to be quite a piece of work, psychologically speaking. But how do you arrive at a useful profile?

The raw destruction of Kaczynski’s actions make him easy fodder as the character of one-dimensional evil, or one-dimensional insanity, or both. But later series episodes surprise us with the sympathetic light cast on Kaczynski’s past torments, and his bucolic lifestyle. His egregious betrayal by a Harvard professor he admired alone invites another entire mini-series.

There’s so much to explore here we’ll return from time to time to dive down these tunnels of psychology and logic.

Meanwhile do yourself a favor. Stream the series.