In one of the many documentaries about “Custer’s Last Stand,” narrator Dick Cavett begins by asking: why the undying interest in all those dead soldiers? Why is the Battle of the Little Big Horn one of the most studied, and storied, battles of all time? It held, after all, almost no strategic importance in the long run, and the number of casualties from both sides, although tragic, were eclipsed by countless other battles in countless wars. So why all the fuss?

In one of the many documentaries about “Custer’s Last Stand,” narrator Dick Cavett begins by asking: why the undying interest in all those dead soldiers? Why is the Battle of the Little Big Horn one of the most studied, and storied, battles of all time? It held, after all, almost no strategic importance in the long run, and the number of casualties from both sides, although tragic, were eclipsed by countless other battles in countless wars. So why all the fuss?

“What, then, is the persistent appeal of Custer’s final fight?” asks Cavett. “Perhaps it’s the mystery.”

Very little is clearly, indisputably known about the closing moments of the battle now wrapped in “myth and legend.” Although there were no survivors from Custer’s direct command the Native survivors passed down stories in a rich oral tradition, and archaeological reconstruction of artifacts and bones of fallen soldiers have revealed patterns. But the battle ranged across hills and valleys too wide for any one pair of eyes to see. We reconstruct old battles, the tragedies of old massacres, as best we can from the stories that travel through time, and through the skeletons that speak with a bony silence.

We wonder what the scene would have really looked like, what the details really were. Nineteenth-century journalists who never saw the battlefield, had never even been in the West, filled the newspapers of the time with rich, fanciful accounts. As if they’d been there in hand-to-hand combat with Sitting Bull, themselves.

The fanciful accounts continue, even today. Do some of them contain grains of truth, or at least the pregnant questions we should answer to finally grasp The Last Stand?

A popular documentary series, “The World’s Greatest Mysteries,” recently revisited Little Big Horn with a conspiratorial eye. Its group of assembled experts may not be the ultimate authorities, but they do remind us of provocative questions:

Did Custer have up-to-date and accurate intelligence on the astounding numbers of Natives assembled against him, and were his Indian scouts trustworthy? Did he trust them, and how did that play in his psychology–perhaps the fictional “Little Big Man” merits another look.

Was Custer aware just how many rifles had been distributed to Natives to hunt buffalo, Winchesters that fired rounds much more rapidly than the carbines issued his troopers? Did he truly leave his Gatling guns behind due to his aggressive, fast moving battle style, or did he receive orders to do so, lost in time?

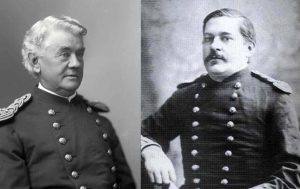

Why did neither Captain Frederick Benteen nor Major Marcus Reno come to Custer’s aid from several miles away, when a courier successfully delivered an order to do so? Reno had already suffered severe losses in a skirmish, and the dangers of reaching Custer’s position were obvious, but Benteen had a direct, written order in hand. Did the officers’ personal distaste for Custer play a role, or did they simply see the cause as lost and choose not to sacrifice a new supply of soldiers?

At conspiracy’s razor-edge, could President U.S. Grant’s personal loathing of Custer have factored in, perhaps in secret communications that have never surfaced?

One historian interviewed–an attorney and retired military officer–concludes that Custer and his men were set up.

For one thing, the official inquiry seemed fishy: “several witnesses told of receiving pressure to make their testimony fit” asserts the program. If testimony had to be shaped deliberately, just who needed to sculpt a myth, and why?

One Captain Thomas Weir, an officer who served at The Little Big Horn riding with companies not directly under Custer that day (and incidentally someone friendly with Mrs. Custer), was rumored to have a lot to say concerning the massacre. He was not called to testify at the inquiry. Why not? He died of alcohol related disease, aged thirty-eight, just a couple of months later. He had gone from healthy Indian fighter on the plains to death in surprisingly short order. Was it merely a case of his noted depression, his despair at having been helpless near Custer’s demise, or could he have offered scandalous testimony?

Researchers for this documentary asserted that a visit to the Library of Congress, to review archived military communication regarding the Little Big Horn campaign, met with helpful staff and lots of contextual documentation. But conspicuously missing were all telegrams sent to or from Colonel Custer at the time. The researchers were told those documents had been missing for over a century, since shortly after the massacre, whereabouts unknown…

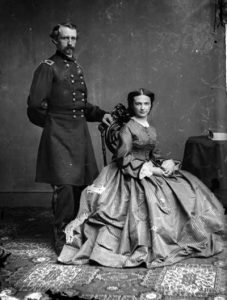

Colonel Custer’s widow, the bright and spirited Elizabeth Custer, spent the last fifty-seven years of her life defending her husband’s honor, insisting in valiant sacrifice as the only posture for the fallen soldiers. Her motives as a grieving widow, living the rest of her life floating upon her husband’s reputation, are rather obvious. And the question is fairly asked, what were the motives of high ranking army and government officials as they constructed the story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, of the worst defeat for U.S. forces in all of the Indian campaigns?