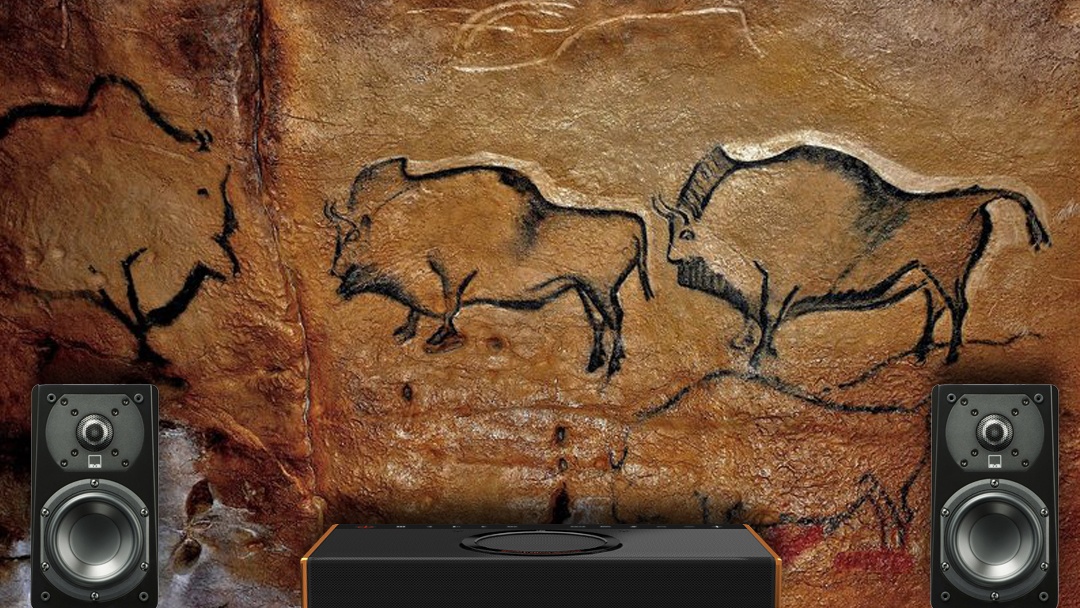

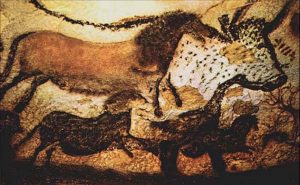

Very early in the 20th century a French naturalist named Rene Jeannel discovered prehistoric art in caves in southern France, near the Spanish border, that redefined the archaeological orthodoxy about early man and artistic expression.

Scientists and researchers, never ready to accept conventional wisdom when someone can take ideas in new directions, innovate even in “cave wisdom.” Just for example, archaeoacoustics, the field of studying earlier life and civilizations by means of the sounds patterns that (might have) held forth in their everyday lives.

A modern researcher analyzed the acoustic patterns in the caves, noting that some areas “have richer sound than others.” And even more significantly, it seemed that the art on the walls centered around the acoustically rich areas.

A modern researcher analyzed the acoustic patterns in the caves, noting that some areas “have richer sound than others.” And even more significantly, it seemed that the art on the walls centered around the acoustically rich areas.

Should that really be surprising at all? Prehistoric humankind, undistracted by smart phones, traffic jams, and deadlines for filing taxes, operated on their primordial senses. He and she, sniffing, touching, scanning the horizon, may have been as far removed from us as our dogs and cats are today in sensory priorities.

As they attempted to represent bison and other animals with paint, they may very well have imitated their sounds, moaned them out loud. The sounds of these animals were likely more real to them than the first cave paintings.

As they attempted to represent bison and other animals with paint, they may very well have imitated their sounds, moaned them out loud. The sounds of these animals were likely more real to them than the first cave paintings.

Perhaps every day was a rock concert for prehistoric beings, with meaning and power from the surrounding sounds. Archaeoacoustics, the emerging field, may help us understand just what part sound played in their environments.