Mary Pinchot Meyer

It may raise unanswered questions forever: the violent death, at age 44, of Washington socialite Mary Pinchot Meyer, on October 12, 1964. This was less than eleven months after the death of her lover, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, also by gunshot wounds to the head.

The Pinchot family were aristocrats and Mary grew up with class, education, and beauty. In her youth she married a rising star in government work, Cord Meyer, and his career in the CIA led him into the upper ranks of officials with influence over, and connections within, the underworld of spies and national security secrets. They divorced, but Mary never lost her links to a very connected, and fascinating, Washington world. As an attractive, intelligent, and dynamic divorcée Mary could have chosen relationships with any number of men, but one she valued the last few years of her life was with the most seductive womanizer on the landscape, the young President. We’ll never be privy to the nature of their intimate moments, of course, but JFK enjoyed their time together due to Mary’s superior intelligence and her highly adventurous spirit. Then November 22, 1963 and everything in the nation’s capitol changed.

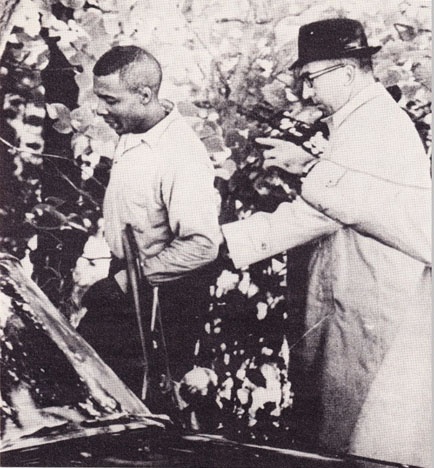

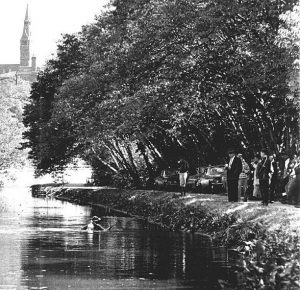

On October 12 of the following year Mary was walking as she frequently did along a path near a canal in her Georgetown neighborhood. Distant observers heard a scream, gunshots, and by the time anyone reached the scene, Mary lay dead of a shot to the head, another through the heart. A seeming drifter, who roughly fit the description of a shooter at the scene, was encountered by police while wandering around the canal, detained, and eventually tried for Mary’s murder. Although circumstantial evidence pointing to his guilt was substantial, he was ultimately acquitted.

On October 12 of the following year Mary was walking as she frequently did along a path near a canal in her Georgetown neighborhood. Distant observers heard a scream, gunshots, and by the time anyone reached the scene, Mary lay dead of a shot to the head, another through the heart. A seeming drifter, who roughly fit the description of a shooter at the scene, was encountered by police while wandering around the canal, detained, and eventually tried for Mary’s murder. Although circumstantial evidence pointing to his guilt was substantial, he was ultimately acquitted.

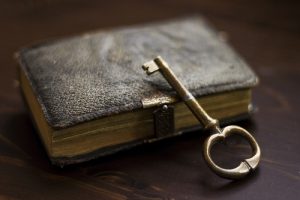

The death of Mary Meyer stands, officially, as an unsolved murder, only one among thousands. What elevates it to the status of a significant mystery, however, are all the circumstances, the stage, if you will, on which Mary was shot. A dozen intriguing questions remain unanswered. Only hours after her death Ben Bradlee, friend of JFK and later of Watergate fame as the editor of the Washington Post, entered her home to secure her personal diary, but found high-level CIA official James Angleton already there, searching. Bradlee had a more intimate connection—through his marriage to Tony Pinchot, Mary was his sister-in-law. A staggering array of stories and theories conflict on what her diary and papers may have contained, and what happened to them. None of those documents survived, to help write history.

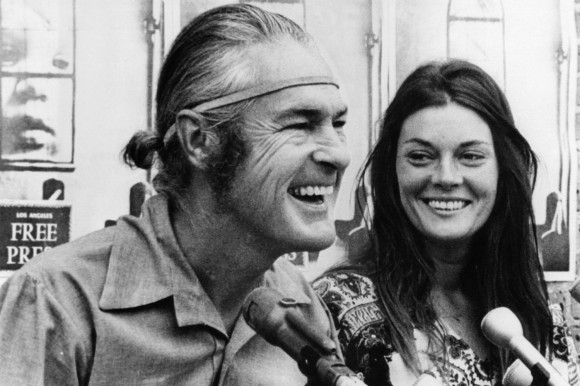

It was often reported that Meyer took an intense interest in the assassination of the preceding November, and committed her suspicions to writing. One inevitable speculation is that someone silenced her, deliberately. A number of rumors and theories cover ever more interesting ground. The Harvard psychologist-turned-LSD proponent, Dr. Timothy Leary, related numerous contacts with Mary in which she hinted that Washington’s highest powers were now experimenting with new consciousness, and new drugs. Would the contents of her diary have spawned the scandal of the century? Little about Mary’s demise is known for sure, but one thing is almost certain: that if historians ever got a look at that diary, eyebrows would have been raised.

It was often reported that Meyer took an intense interest in the assassination of the preceding November, and committed her suspicions to writing. One inevitable speculation is that someone silenced her, deliberately. A number of rumors and theories cover ever more interesting ground. The Harvard psychologist-turned-LSD proponent, Dr. Timothy Leary, related numerous contacts with Mary in which she hinted that Washington’s highest powers were now experimenting with new consciousness, and new drugs. Would the contents of her diary have spawned the scandal of the century? Little about Mary’s demise is known for sure, but one thing is almost certain: that if historians ever got a look at that diary, eyebrows would have been raised.

Join us as we open the file: The Curious Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer.

WHAT THE PUBLIC UNDERSTANDS

She met John F. Kennedy at a prep school dance and in the early 1960s, began an affair with the president that lasted until the time of his assassination. One year later, on Oct. 12, 1964, Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot dead while taking an afternoon walk on a Georgetown towpath in Washington, D.C., at age 43.

Nearly fifty three years later, her murder remains unsolved. Was it a random act of violence or did someone want her dead?

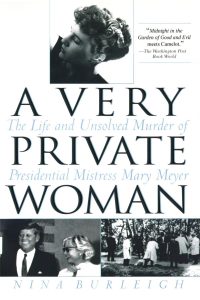

“She was shot in the head,” says author Nina Burleigh, who wrote about artist and socialite Pinchot Meyer in the 1999 biography A Very Private Woman. “Passersby heard screams and a witness looked over the wall and saw a man standing near her body. The police came and shortly arrested a black male [Ray Crump Jr.] soaking wet who said he fell into the Potomac while fishing. … No gun was ever found.”

Crump Jr. pled not guilty and was acquitted at trial for lack of evidence in July 1965.

While he is still the only suspect, there have been theories that Pinchot Meyer’s death may have been linked to her affair with JFK. Says Burleigh: “The theory is that she had to die because she knew too much.”

”Her murder just ten days after the Warren Commission report was released makes a lot of people suspicious that she had to be silenced,” Burleigh notes, adding: “She lived in a world of secrets … the secrets of spies running complicated international plots, trying to control a dangerous world at the dawn of the nuclear age.”

Adding to the mystery, in the hours after Pinchot Meyer’s death, chief of CIA counterintelligence James Jesus Angleton broke into her artist studio (which was attached to her brother-in-law Ben Bradlee’s house) to find her diary.

People.com/politics, September 25, 2017

Sometimes a light-hearted outlet like People Magazine writes excellent summaries of complex situations, and the excerpt above is a good introduction to the remarkable Mary Meyer story.

The best analysis starts with the best questions, and here are several:

- Although Mary’s daily walk along the towpath was routine, her shooting seemed odd. She carried no purse, nor valuables. How likely is it that a random guy from another part of town would engage with her, and be so offended over something he would shoot her in the heart, and head (vaguely but not completely) gangland style?

- A wet, rumpled Ray Crump and his story seemed fishy, no play on words on the fishing pole that supposedly had slipped off into the river. But much later it seemed clear the married man had a tryst on the river’s bank, something he wanted to keep very quiet. Crump was acquitted, but was that the work of an over-competent defense attorney, or the right call?

- After Crump’s acquittal the DC police lost interest in the case, considering it “solved,” with the guilty party having slipped away from justice. Were they influenced by anyone to drop pursuit of the case, and trash most of the files? Documentation on a capital case of this sort should have been preserved, forever.

- Absolutely no one seems to doubt that one of the top spies on the planet, high-ranking CIA official James Jesus Angleton, had so much interest in Mary’s “diary” that he broke into her home to search for it–-journalist Ben Bradlee (brother-in-law) encountered him. In many versions of the story Angleton came by twice in a focused search for documents. A woman who was merely the wife of a CIA official (Cord Meyer), and a divorced wife at that, what national security interest could her papers hold?

- Mary was said to have been outspoken about Jack Kennedy’s assassination, and quite skeptical of the recently released Warren Report. Could this have any bearing on her demise, or the search through her documents?

- More bizarrely, Mary was part of a hip-coterie who enjoyed LSD, and may have influenced high government officials to experiment as well. Timothy Leary made extraordinary claims about his dealings with her, many years after the fact. Significant, or the ravings of an old “acid-head?”

- Washington-based CIA activities seem to have almost ground to a halt for a day or two at the time of Mary’s death, and funeral. In the normal case wouldn’t it have been business as usual, with a one or two hour absence from the office to attend the funeral of the ex-wife of a colleague?

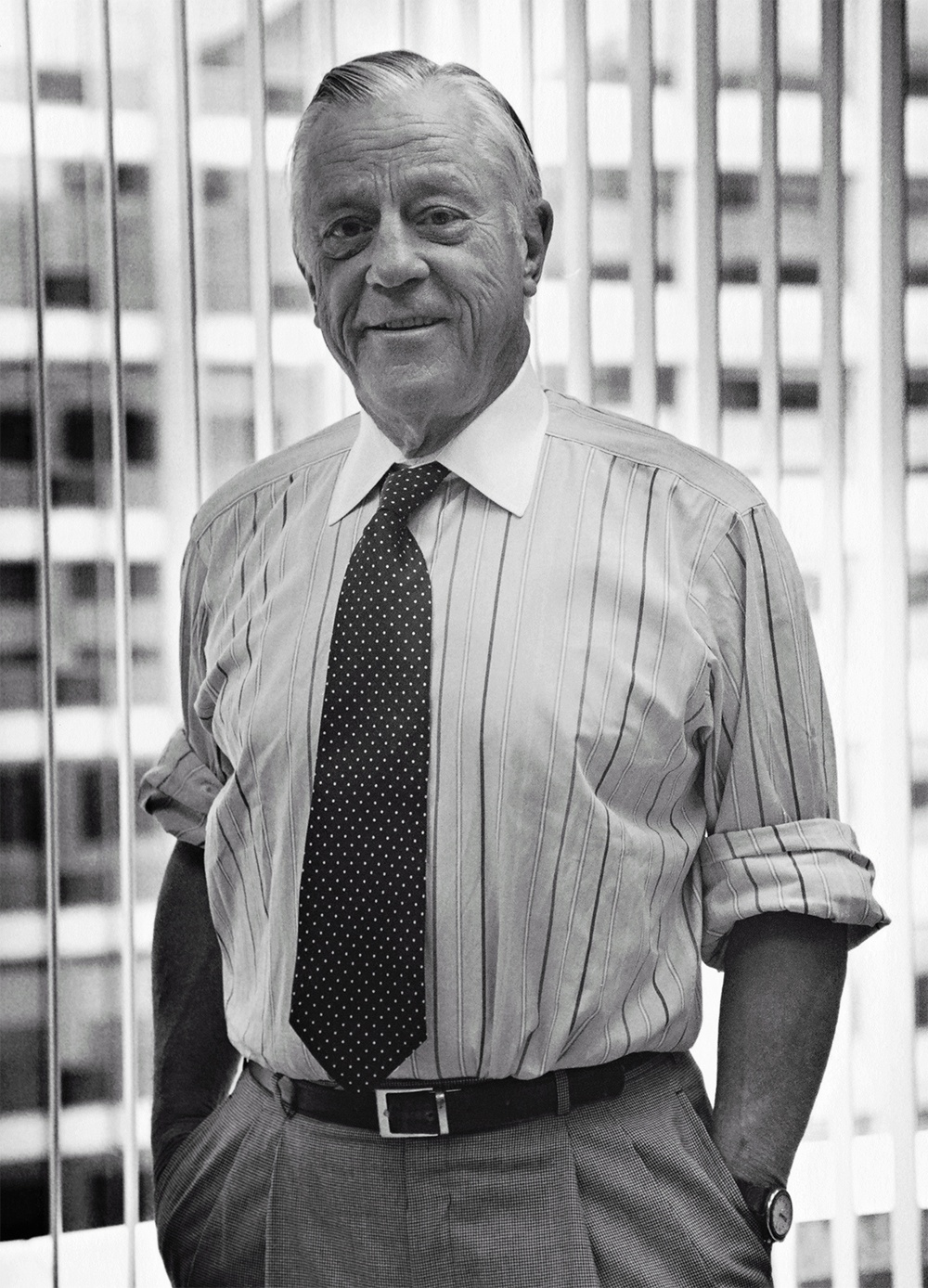

- Well connected journalist and brother-in-law Bradlee spoke sparingly of the situation the rest of his life. But when he did, his story always shifted a little. What did he really know, and was he protecting family, or other actors?

MARY’S STORY, AS ALWAYS DEVILS AND DETAILS

Air Force Lieutenant William Mitchell passed two people walking west as he was running east along the towpath that day. The first person he claims to have seen was a woman whose description closely matches that of Mary, and the second was a man walking in the same direction, about 200 yards behind her. Mitchell described the man as being about the same height as him, and “wearing a light colored wind breaker, dark slacks, and a peaked golf hat” (Nobilem and Rosenbaum 22).

Air Force Lieutenant William Mitchell passed two people walking west as he was running east along the towpath that day. The first person he claims to have seen was a woman whose description closely matches that of Mary, and the second was a man walking in the same direction, about 200 yards behind her. Mitchell described the man as being about the same height as him, and “wearing a light colored wind breaker, dark slacks, and a peaked golf hat” (Nobilem and Rosenbaum 22).

Henry Wiggins, who worked at the M Street Esso station, was called to the area of the towpath that day in order to jump start a gray Rambler with a dead battery. As he got to the vehicle on Canal Road, he heard a woman yell, “Someone help me, someone help me,” from the towpath down below (Nobilem and Rosenbaum 22). He then heard two gunshots and ran to the edge of the wall overlooking the towpath. He “saw a black man in a light jacket, dark slacks, and a dark cap standing over the body of a white woman…” (Nobilem and Rosenbaum 22). According to Wiggins, the man then placed a dark object in the pocket of his windbreaker and disappeared into the wooded embankment leading down to the Potomac.

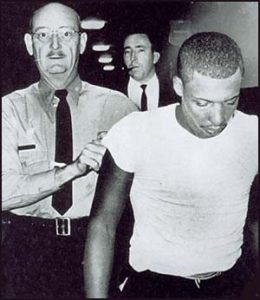

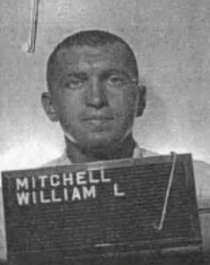

Officer escorting Ray Crump Jr.

Wiggins jumped in his truck, sped back to the Esso station, and called the police department. Within five minutes of the phone call, police converged on the towpath and sealed off all of the five well-marked exits. Convinced they had the murderer trapped, police began to scour the towpath area.

Officer Warner came across the only live person on the towpath: a black man named Raymond Crump Jr. who was dripping wet. He was wearing dark slacks and a peaked golf cap. Even though it was a brisk day, he had no jacket with him and his pants zipper was open. Crump said he had gotten wet when he lost his fishing pole and went into the river to try and retrieve it. Moments later, when Crump was showing Officer Warner where he claimed to be fishing, Henry Wiggins saw the two of them down by the river and started yelling to police that that was the man he saw kill Mary Meyer. Raymond Crump Jr. was then arrested. When asked why his fly was down, he said the police did it.

Ben Hayes, macadams.posc.mu.edu, posting date unknown

This post from a serious, Marquette University faculty blog on mystery analysis, hints at the complex semi-urban, but semi-rural scene. Were the exits really sealed off, did law enforcement have their perpetrator trapped? At this distance of years, and lacking firm documentation, we consider that an open question.

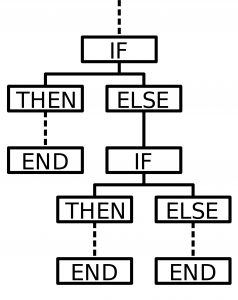

There’s a score or more of IF this, THEN that turning points in the Meyer story.

IF there really were “help me” screams for several moments from Meyer, that does lead away from the theory of a contract-type hit. Professionals usually shoot quickly, silently, and then leave immediately. But IF the remarks were only the squeak of a second when Mary quickly perceived violent intent, they could be consistent with a professional, who knew how to place shots to kill.

IF Raymond Crump really had no alibi for why he was wandering around wet, far from his home turf, lots of circumstances look bad for him. IF he choose the remote spot for clandestine, illicit sex, and the shy woman took off at the first sign of trouble, that could make some sense. We are carrying the weight of much speculation, many an IF…

IF Crump met a woman for an escapade that day, how likely is it that a rape attempt would be on his mind, either before, or after? A rape gone wrong merits frequent mention as the panicky motive for Crump’s supposed crime. Or was he not bright enough to see that a woman walking in her neighborhood with no pocketbook really offered nothing to steal, so he attempted a botch robbery? That also doesn’t seem quite right.

And normally we reject thinking that assumes too much brilliant planning on the part of nefarious conspirators. But IF Crump was somehow set up, he would be the perfect fall-guy– black, poor, confused, vulnerable to pressures.

We can swim in IF’s in these cases for a long, long time.

“Two telephone calls that night from overseas added new dimensions to Mary’s death. The first came from President Kennedy’s press secretary, Pierre Salinger, in Paris. He expressed his particular sorrow and condolences, and it was only after that conversation was over that we realized that we hadn’t known that Pierre had been a friend of Mary’s. The second, from Anne Truitt, an artist/sculptor living in Tokyo, was completely understandable. She had been perhaps Mary’s closest friend, and after she and Tony had grieved together, she told us that Mary had asked her to take possession of a private diary ‘if anything ever happened to me.’ Anne asked if we had found any such diary, and we told her we hadn’t looked for anything, much less a diary. We didn’t start looking until the next morning, when Tony and I walked around the corner a few blocks to Mary’s house. It was locked, as we had expected, but when we got inside, we found Jim Angleton, and to our complete surprise he told us he, too, was looking for Mary’s diary”.

Ben Hayes, macadams.posc.mu.edu, posting date unknown

So, What does this tell us? Mary had lots of connections, which could mean a lot, and could mean nothing.

And that “diary,” as it kept being called? We know at least that Mary considered it somewhere on the scale of very private, to absolutely explosive. Where on that range, we don’t know. But we do know that absence makes the curiosity grow fonder, if not the heart. Those papers are long gone, it seems.

Were there explicit revelations of her affair with President Kennedy? Which would now, after all these years and other revelations about his appetites, seem rather tame.

Or did her speculation, even knowledge, of government affairs go well beyond the bedroom? IF we knew, we’d know where to go with that part of the puzzle.

THE CIA, OF COURSE, WHO ELSE?

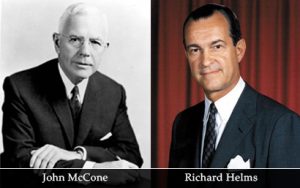

The fact that Mary’s death concerned the CIA bigwigs is noted in a declassified, heavily redacted FBI memo regarding the rescheduling of a meeting between CIA director John McCone and Helms and FBI officials. The reason for the meeting is not stated in the memo, which was written by an FBI agent named William C. Sullivan, J. Edgar Hoover’s number-two man. “On 10/14/64, Helms advised the Liaison Agent that it will be impossible for CIA officials to meet with me and Supervisor [name redacted] on 10/14/64, and suggested that the meeting be held at 10:00 a.m. 10/15/64. Helms explained that both he and Angleton have been very much involved with matters pertaining to the death and funeral of Mrs. Mary Pinchot Meyer. She is the woman who was murdered on the canal towpath near Georgetown on 10/12/64. She was the former wife of Cord Meyer, a CIA official.” In an interview, Helms could not recall exactly what personal involvement the memo noted beyond his attendance at the funeral.

The fact that Mary’s death concerned the CIA bigwigs is noted in a declassified, heavily redacted FBI memo regarding the rescheduling of a meeting between CIA director John McCone and Helms and FBI officials. The reason for the meeting is not stated in the memo, which was written by an FBI agent named William C. Sullivan, J. Edgar Hoover’s number-two man. “On 10/14/64, Helms advised the Liaison Agent that it will be impossible for CIA officials to meet with me and Supervisor [name redacted] on 10/14/64, and suggested that the meeting be held at 10:00 a.m. 10/15/64. Helms explained that both he and Angleton have been very much involved with matters pertaining to the death and funeral of Mrs. Mary Pinchot Meyer. She is the woman who was murdered on the canal towpath near Georgetown on 10/12/64. She was the former wife of Cord Meyer, a CIA official.” In an interview, Helms could not recall exactly what personal involvement the memo noted beyond his attendance at the funeral.

The “Angleton” referred to in the memo was Cord Meyer’s closest friend and fellow Yale graduate, James Jesus Angleton, second only to J. Edgar Hoover as the nation’s greatest collector of personal secrets. Angleton had been personally close to Mary as well. He occupied the post of CIA counterintelligence chief, charged with deciding which of America’s spies might be traitors. Half Mexican, half Anglo-Saxon, Angleton was stooped and cadaverous, with fingers stained yellow from years of heavy smoking. Angleton’s passions included Italy and anything English, dry-fly fishing, and raising orchids. He had a reputation for paranoia. He never opened the blinds in his office and kept the drapes pulled on top of them. He was rarely seen. CIA official David Atlee Phillips said Angleton was so reclusive, Phillips mistook another man for Angleton for fifteen years. His pronouncements were taken seriously. Some called him “the CIA’s answer to the Delphic Oracle.”

Among his many responsibilities in the fight against global Communism, Angleton made it his business to stay on top of the private affairs of the denizens of Georgetown, men and women with complicated lives so intimately connected to the heart of the national government that they seemed obvious targets for any enterprising Communist looking to do blackmail or, worse, recruit a traitor. On the day of Mary’s funeral Angleton already had in his possession the diary and letters that told the story of Mary Meyer’s personal life. They had been handed to him by journalist Ben Bradlee in an act motivated equally by family embarrassment and patriotic duty. Later Angleton would boast that he had also bugged Mary Meyer’s telephone and bedroom.

Angleton served as an usher at Mary’s funeral, leading the mourners to their seats in the chapel, but he felt Bradlee had devised the funeral more to impress social Washington than to honor the dead woman. He smiled when he saw one of Mary’s close friends, Otakar “Kary” Fischer, a Czech immigrant who edited a scholarly journal of Soviet studies called Problems of Communism. As he walked Fischer to his seat, Angleton surveyed the gathered members of Georgetown society and whispered in disdain, “We were her true friends, you know.”

Cord Meyer oversaw a large staff at the CIA, which accounts for the presence of so many spies at the funeral. In the two decades after World War II, the CIA had grown far beyond its initial executive charter, and nearly beyond the will of the men who created it. The agency operated from a new building in Langley, Virginia, and its huge budget and vast projects were unknown to the American people. The responsibilities of the labyrinth they had constructed were already starting to drive some of the men mad, many to drink, and more to cut moral corners.

From “A Very Private Woman,” 1999, Nina Burleigh, pps. 17-19.

Nina Burleigh has written some gems of long-form journalism on deep topics. Her book on the Amanda Knox case is a modern classic.

Does Burleigh suggest to much here, too little?

Is it possible that the fuss at the CIA about Mary’s death was only due to Cord Meyer’s stature at the agency, that his subordinates knew what a wreck he would be, and acted accordingly? Some find it hard to picture how planning to attend a funeral, even helping out with flowers and arrangements, would result in rescheduled meetings of great importance.

The heavy presence of “spooks” in the scenario probably owes to nothing more than Mary’s many years as the wife of a central CIA figure, as the author suggests.

We do respect the right of analysts, however, to find it interesting how the hand of the CIA seems to touch such a great number of sensitive deaths, disappearances, or changes in political power.

Over-heated conspiracists undoubtedly give the agency way too much credit for altering the landscape behind the scenes, but it’s easy, as well, to underestimate activity just below the surface of the water.

Part of the American landscape of political mystery, for good or ill, always has the CIA in costume, if only just offstage, waiting to appear at odd moments.

There’s no proof that any government organ had any involvement with Mary’s death.

In fact, it can be argued that a hit by professional spooks would have been much simpler. She lived alone. So, have a trained assassin feign a break-in at her home and quickly kill her indoors, cleanly. Take a few things to sustain the robbery theory, and in the bargain harvest that pesky diary.

Why go through all the risk and commotion of a complicated outdoor killing, when the loose ends are so easily tied up under her roof, in a few minutes, by one or two persons?

Nonetheless, her demise would have been a relief to the straight-laced national security types. She represented a free spirit, anathema to those types. She was never read in to the details of her husband’s work, we assume, but still knew too much for someone with a loud voice. Worse still, she was known to experiment with drugs, even LSD, and to certain CIA types she must have seemed as threatening in her way as a Soviet ICBM.

They may not have killed her, some may even have enjoyed her socially, but Washington’s CIA establishment must have breathed a bit easier after her death.

AT THE END OF THE DAY, WHAT HAPPENED?

….over the years, sensational fragments of the story (JFK, CIA) turned up. Inevitably, conspiracy theories emerged. Who killed Mary—really? Was Ray Crump set up? By whom? Why?

As real evidence went mute, the public imagination worked on two possible narratives.

The first was what might be called the Oliver Stone Solution—that is, to posit a conspiracy elaborate enough and sinister enough to do imaginative and, as it were, cinematic justice to the murder of a woman with such suggestive, powerful connections. The journalist Nina Burleigh sifted through plot possibilities in her excellent book on Meyer, A Very Private Woman (1998), and quoted the critic Morris Dickstein on the temptations of the 1960s’ paranoid style—“a sense at once joyful and threatening that things are not what they seem, that reality is mysteriously overorganized and can be decoded if only we attend to the hundred little hints and byways that beckon to us.”

Thus in the Stone Solution, popular on the Internet, Meyer was done in by “the same sons of bitches that killed John F. Kennedy,” as one writer, C. David Heymann, claims he was told by the dying Cord Meyer. Another writer, Leo Damore (also dead), argued that Crump “was the perfect patsy, better even than Lee Harvey Oswald. Mary Meyer was killed by a well-trained professional hit man, very likely somebody connected to the CIA”—the idea being that she knew “too much for her own good.”

The second scenario might be called the Richard Wright Solution, after the author of the 1940 novel Native Son, whose protagonist, Bigger Thomas, is tormented by the oppressions of poverty and racism: “To Bigger and his kind white people were not really people; they were a sort of great natural force, like a stormy sky looming overhead, or like a deep swirling river stretching suddenly at one’s feet in the dark.” In this scenario, Crump one day left his home in black Southeast Washington, crossed the segregated city, passing the Capitol and the White House, and entered white Georgetown. And there—on the home turf of mandarins, of Joe Alsop and Kay Graham and Scotty Reston and Dean Acheson—his path intersected for a moment with Mary Meyer’s.

You could choose your movie. Solution One drew Mary Meyer into the world of James Ellroy, the grassy knoll, Jim Garrison, the Mafia, Judith Exner, Fair Play for Cuba, Operation Mongoose and so on. Solution Two inserted Mary Meyer by accident into an entirely different story: the primal drama of race in America.

The Oliver Stone Solution regards Ray Crump as misdirection. The Richard Wright Solution regards the conspiracy as misdirection. I don’t buy either—the conspiracy theory smacks of the Oedipal paranoid (fantasies of hidden plots by sinister super-elders), and the other doesn’t cover the particularities of this act. (At the same time, given what the two witnesses said, and given Crump’s alcoholism and mental instability and criminal record before and after the murder, I believe the jury erred in acquitting him.)

From Lance Morrow, The Smithsonian, December, 2008

Morrow hits upon the intrigue, and the thin evidence, that sustains any given theory, even the official one. Mary’s murder, in the end, drowns in question marks.

The possibilities are not binary, simple either-or. Instead they dance across our imagination like the colors of a prism, even a kaleidoscope of possibilities. In continuum style, some of the takes on her demise.

- The Occam’s Razor theory (that the simplest, most obvious explanation is almost always the right one) stands up like a flagpole of simple, common sense: Mary died in a crazed act of random violence, as, sadly, thousands do every year. Even the mystique of her “diary” and affair with JFK only seem significant when you wrap them inside a “mystery murder.”

- Mary’s encounter with deadly violence may have just been horrid luck, but the CIA reaction afterward, that’s a different story. Come on, the country’s highest level spies cancel big meetings and break into a dead lady’s home because they have nothing better to do with their time? At least, written reminiscences of a very forbidden affair, involving the highest profile man in the world, needed to disappear.

- The illicit affair was probably the least of it. As quite the Washington insider Mary knew, or thought she knew, a lot of government secrets. Even if her papers were filled with overblown, bogus speculations, the potential to embarrass official Washington was much too great.

- Yes, she posed a threat, and it had something to do with her death. Why do we believe that a hapless, largely shy little black man would be tussling with this white stranger and then executing her by revolver? Out of character, and not connected by common sense to a man meeting his mistress on the river bank for some illicit pleasures of his own. Something more than meets the eye led to those fatal shots.

- When the CIA performs a black op, they can do it up right, with all the props and stage hands that they need. As in author Peter Janney’s sketch, the spooks had spotters along her usual walking path, a plan for a “double” of Ray Crump to dispatch Mary with deadly placed shots, and the timing to get the real players and murder weapon out of the picture fast. The best Hollywood director couldn’t have choreographed the whole thing more perfectly. Just as films are designed with illusion, this killing was designed to look like the act of a lone “sad sack,” a random citizen.

BEHIND THE VEIL

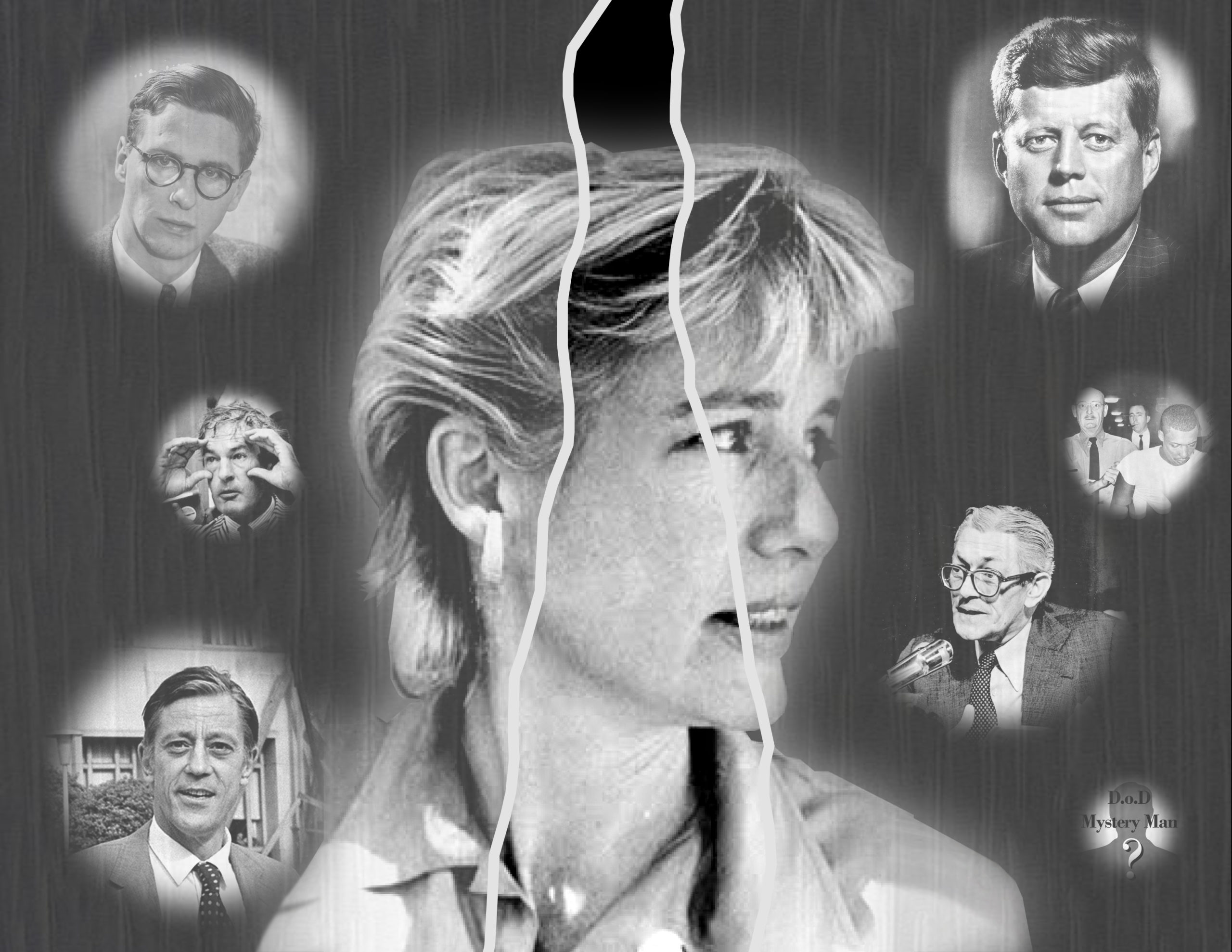

JFK… Ray Crump Jr…James J Angleton…the Department of Defense “Mystery Man” …Ben Bradlee…Timothy Leary…and Cord Meyer… these are all part of The Story Behind The Story.