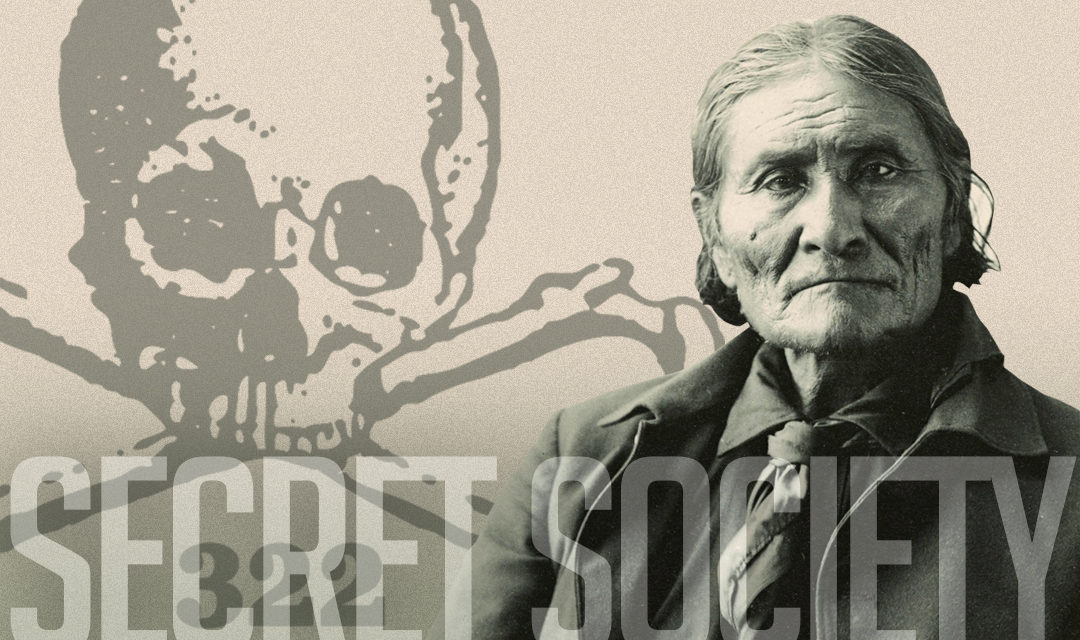

Geronimo

Few stories are more troubling, and suggest more questions, than the demise of the notorious Apache they called Geronimo, and the controversy surrounding the location of his remains. Late in the warrior’s life Geronimo had surrendered to U.S. forces, and lived out his days on government property first in Florida and Alabama, and finally Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. Officially, a tomb at Ft. Sill forever guards the bones of the most infamous Indian warrior who ever lived.

Few stories are more troubling, and suggest more questions, than the demise of the notorious Apache they called Geronimo, and the controversy surrounding the location of his remains. Late in the warrior’s life Geronimo had surrendered to U.S. forces, and lived out his days on government property first in Florida and Alabama, and finally Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. Officially, a tomb at Ft. Sill forever guards the bones of the most infamous Indian warrior who ever lived.

But do we really know that to be the case? Legend and myth loom over the Apache, and their relations to an American army that almost exterminated them, like dark thunderclouds over the Southwest deserts in summer. For example, documents exist boasting that in 1918 a young soldier and his comrades, while stationed at Ft. Sill, secretly dug up the contents of Geronimo’s grave, and sent the skeletal remains back East. The tale rises as so startling, and compelling, because the young officer in question was Prescott Bush, father of one American President and grandfather of another. Compelling, also, because the destination of the robbed remains was the secretive Skull and Bones Society at Yale University, where supposedly the skull of Geronimo was on display, a trophy, for decades afterward.

But do we really know that to be the case? Legend and myth loom over the Apache, and their relations to an American army that almost exterminated them, like dark thunderclouds over the Southwest deserts in summer. For example, documents exist boasting that in 1918 a young soldier and his comrades, while stationed at Ft. Sill, secretly dug up the contents of Geronimo’s grave, and sent the skeletal remains back East. The tale rises as so startling, and compelling, because the young officer in question was Prescott Bush, father of one American President and grandfather of another. Compelling, also, because the destination of the robbed remains was the secretive Skull and Bones Society at Yale University, where supposedly the skull of Geronimo was on display, a trophy, for decades afterward.

To imagine the Native reaction to the legend, just think of the outrage if it were known that John Kennedy no longer lay resting under that eternal flame. That Natives had robbed the grave and taken the remains away, for their own amusement. Such a desecration would drive a bitter story for years, eliciting anger and revulsion in equal parts. And yet, the possibility that an exclusive Ivy League society, representing the continuity of American power and privilege, has used Geronimo’s skeleton for sport has barely created a ripple in the public consciousness, outside of the Native American community.

Two members of Skull and Bones, John Kerry and George W. Bush, vied for the presidency of the United States in 2004—whatever the election outcome, the chief executive would be a Bonesman, as the phrase goes. Such is the reach of exclusive organizations linked to power and leadership. John Kerry, asked about his membership in the secret organization allowed that yes, he was a member, but no, he was going to speak no further about the activities of the society…quote… “because it’s a secret.”

Two members of Skull and Bones, John Kerry and George W. Bush, vied for the presidency of the United States in 2004—whatever the election outcome, the chief executive would be a Bonesman, as the phrase goes. Such is the reach of exclusive organizations linked to power and leadership. John Kerry, asked about his membership in the secret organization allowed that yes, he was a member, but no, he was going to speak no further about the activities of the society…quote… “because it’s a secret.”

Here at MindOverMystery we have no magic instrument to pierce the veil, but we believe that the the question What Has Become of Geronimo’s Remains? is important to American history, American culture. Please explore with us.

Secrets

Serious Geronimo chasers make at least one pilgrimmage in their lives to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to visit his official gravesite. One Mind Over Mystery Senior Editor made his in the summer of 2015, and here’s the photo to prove it:

Of course, you run into other history buffs there, rolling the same mysteries over in their minds. No one has checked below the ground to see if Geronimo’s remains are really there, and they probably never should. Digging that site up would be pretty disrespectful to his Native traditions, and to the legend.

So the mind wanders, and the mind wonders. Are those really his bones lying under this handsome, respected gravesite? There are a few alternative legends, and theories, about what might have happened, way back in the day. Quite a few of the visitors to the site are skeptical about the bones really being there, below ground.

Long after the supposed white-man’s robbery of the grave, possibly even by one Prescott Bush as legend holds, it seems there was an extraordinary meeting of Ned Anderson, former chair of the San Carlos Apache tribe of Arizona, and representatives of Skull and Bones. Anderson had been tipped off by a former Bonesman, it seems, that Geronimo’s bones really lay in the secret society’s tomb, there admired by generations of members. Obviously Apaches have every right to be mightily offended.

The chairman simply demanded the return of Geronimo’s remains.

From Alexandra Robbins’ 2002 book, “Secrets of the Tomb:”

“Anderson and his attorney set up a meeting with Bonesman Jonathan Bush, brother of then vice-president George Bush…Eleven days later, the duo returned to New York for a meeting with Bush, and Skull and Bones counsel Edicott Peabody Davison…’He said the skull we were interested in was right there on the conference table’….complete with the authentic stirrups and horse bit (in a display case)’ … ‘We had the skull analyzed (the Skull and Bones attorney said)…we found out it’s not Geronimo’s skull, but the skull of a ten-year-boy.’

The Bonesmen then tried to persuade Anderson to sign a document stipulating that the society did not have Geronimo’s skull, that he would take home the display case, and that he would never talk about the matter again. Anderson refused.”

Alexandra Robbins’ 2002 book, “Secrets of the Tomb”

Anderson, back in Arizona, even tried to enlist Senator John McCain’s help–McCain reported back that he couldn’t get Bush to return his calls.

So, as in so many mysteries, the partial answers we get, the stories passed on, raise more questions than they ask.

For example:

- Why would representatives of Skull and Bones, such as Bush and Davison, even agree to meet if their organization didn’t have at least some stolen Geronimo artifacts and a desire to avoid bad publicity?

- Given that Skull and Bones basically wanted the problem to go away, why would they not simply declare from the first that the stories of Geronimo items in their Tomb were only prank-based rumors, without foundation, and leave it at that?

- If there was a robbery of Geronimo’s grave, back in the day, by white men, why was that never discovered, or reported officially? Few grave robberies leave the premises intact, tidy and looking precisely the same.

- Do the Apache have grounds for a criminal, or civil complaint against the Skull and Bones Society, or Yale University? What legal action has been taken—we are researching.

The Riddle

The previous section was white man-controlled narrative on what happened to Geronimo.

The official story regarding his resting place, and the unofficial story of arrogant grave-robbing by privileged elites, have one thing in common. They’re white man’s tales.

Natives have their own legends, and they don’t always share the details of the most intimate tribal matters with outsiders. Why should they?

It’s filtered back to us that certain descendants of the Apaches in question would tell a starkly different story:

“Of course Geronimo’s remains are in a safe place. Do you think we would let them rest under the ‘care’ of the white man, on one of his military bases?”

So according to this narrative, Natives spirited (in several senses of the word) his bones away for truly proper burial. And you can bet that no white man will ever be told just where that is.

As we question and wonder, of course we have to ask: did the Apache leader who met with Skull and Bones know that Native peoples had reclaimed the remains?

Obviously, he wouldn’t have bothered demanding “the return” of the bones if the word among his people was that Apaches had taken them back from Fort Sill, long ago.

Are there different legends within different subgroups, different clans of related but different tribes?

Or did Ned Anderson simply conclude that any stories of his people having recovered the bones were merely ‘wishful legends?’

Is there any irony in an Apache dismissing the tales told by Natives, but appearing to take the legend of grave-robbing Yalies very seriously?

As we continue to, respectfully, explore all this, please weigh in.

Especially if you have real knowledge, especially if you have Apache roots.

The Man & The Meaning

A hundred and fifty years after the last Natives were brought under some form of government control, after the Chiracahua medicine man-warrior called Geronimo had given up the fight, his story, or what we think to be his story, still resonates.

We set aside this section for all those who wish to weigh in, American Native and others as well, on the meaning of Geronimo, and his resting place.

Bring us facts that we might not have known, or passages from the finest writing on the subject, or quotes from Apache or white world sources.

And bring us photos we’ve never seen.