All of our legendary figures, those with a tall mythical status, have more than the average air of mystery about them. As the stories about them grow, rather then recede in our rearview mirror, questions emerge. What was myth… what was reality…and how do we know?

All of our legendary figures, those with a tall mythical status, have more than the average air of mystery about them. As the stories about them grow, rather then recede in our rearview mirror, questions emerge. What was myth… what was reality…and how do we know?

Comes along a general retired from the Bolivian military in the recent news (June, 2017), who says that the Cuban communist leadership had tired of Che Guevara, and were just as happy to get rid of him. Thus the support for his Central American escapades. They figured he would not likely survive guerrilla war in the Americas, leaving them with a win-win. The somewhat too charismatic Che will live on in inspiring memory while the real Che, lately becoming a headache, would be eliminated.

Who tells the story, who first reaches our ears with something we want to believe?

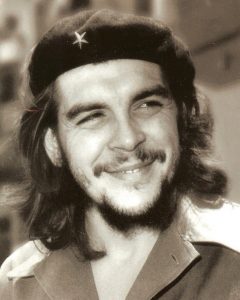

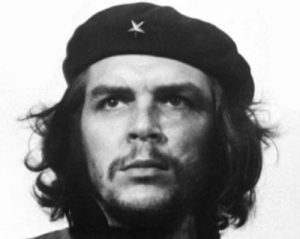

Guevara was clearly more charismatic than either of the Castro brothers, and his media star was rising. He spoke at the United Nations, he was interviewed on the major US television shows, Face the Nation and the rest. He was tele-photogenic and he knew it, a Jack Kennedy among these fiery Marxists. If someone like that, an Argentinian turned Cuban, diverts interest from Cuban homegrown revolutionaries, that’s a problem.

There were other problems. In one speech, Che openly criticized the Soviet Union, which had already become Cuba’s financial lifeline. He was becoming impetuous, quick to pull the trigger on new revolutionary action even before the gains of existing campaigns were solidified. Off to the Congo to fight, he was believed killed there, but survived, and his legend kept growing.

Then Che went to fight for the peasants in Bolivia, with more zeal than realistic planning. Did he and Fidel agree it was high time for him to go, to wage foreign campaigns? His biographer, Jon Lee Anderson, suggests that Fidel was more than ready for Che’s exit. The retired General Prado Salmon adds an emphasis, that the Cuban leadership “rid themselves of him,” that slaps us in the face with its candor.

But, are we sure that’s an honest assessment, not part of the push-back against the Guevara legend and charisma? How would the general, or anyone else outside of Cuba’s inner circle truly know their thinking?

Che, captured alive, was killed by the Bolivian military in October of 1967—and precisely what role the American CIA played in the execution stands as one of the mysteries within the overall intrigue of Che’s story.

Another mystery, the resting place of his bones, was solved by Anderson as he interviewed Bolivian soldiers there at the time. An expedition to the site revealed Guevara’s remains, and those of several others. It’s not uncommon in the wake of political turbulence. We scratch the surface for evidence of one political killing, only to find more buried brutality.

Young students of history and mystery, who only know Guevara as the front of a tee-shirt, might do well to go back and watch film footage from the times. Sitting there for interviews, preternaturally handsome, he charmed even if you don’t understand his long responses, in Spanish, to political questions. Angel or devil, depending on point of view.

How someone like Che could be alternately so very charming, and yet so deeply threatening, speaks to the corner of our psyche that harbors the greatest mystery of all.