Carlos Castaneda

There’s no point in analyzing Carlos Castañeda’s writings in the section called Is It Real, or Nonsense? As serious anthropology, as the non-fiction it pretended to be, the writing was clearly nonsense, and a hoax. As the inspired fiction that it was, it sold widely around the world, and made Castañeda a millionaire.

But there’s more to this psychological and social mystery than the question of how professional anthropologists could award Carlos his doctorate based on the vivid inventions of his imagination. More than the question of how serious academics could fall for one of the century’s greatest hoaxes, and one of its least honest men. There’s much more–for example–the Castañeda women.

At least three of his female intimates, after his death, disappeared and their demise opened its own round of pure, amazing speculation. At least one was found, her bones that is, by a hiker in the barren California desert.

How did one of the great hucksters of his time write such good fiction, animate so many imaginations in positive ways, and yet do so much damage to anthropological science, and the lives of numerous people? Our common psychology begs that question. What in the world happened with Carlos Castaneda?

THE STORY

Those born after about 1980 might not understand the Carlos Castaneda phenomenon, and it’s fairly called a phenomenon, in the same way as those who lived and remember it.

When he died in 1998, The New York Times remembered him this way:

He died of liver cancer on April 27 at his home in Los Angeles, said Deborah Drooz, an entertainment lawyer, friend of Mr. Castaneda and executor of his estate. She said he had suffered from the illness for at least 10 months. After his death, his body was cremated and the remains were sent to Mexico, she added.

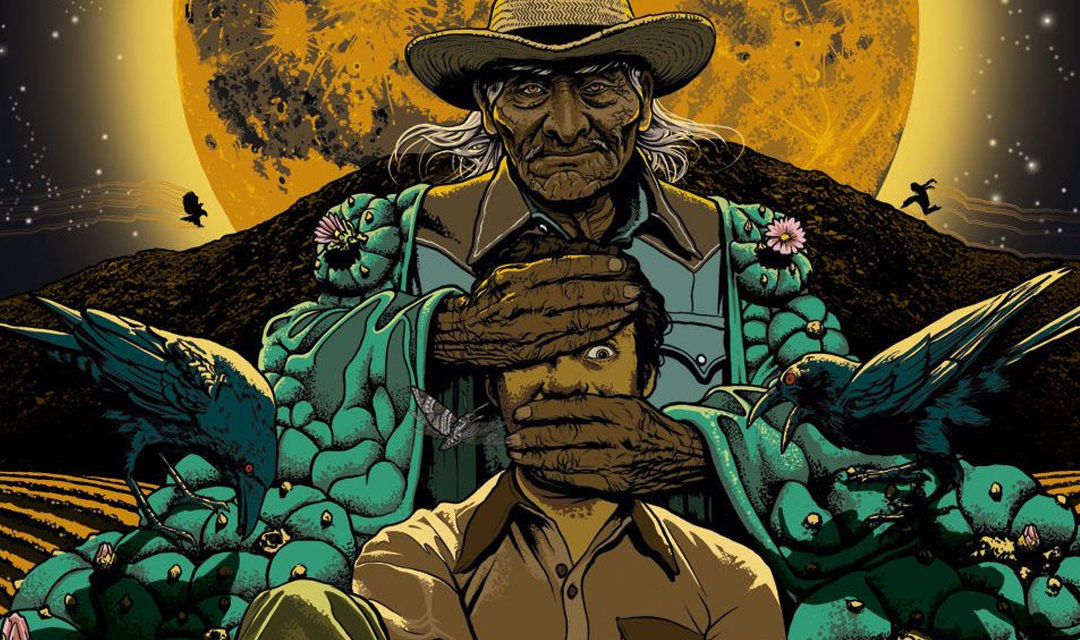

In books like ”The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge,” Mr. Castaneda spun extraordinarily rich, hallucinogenic evocations of ancient paths to knowledge based on what he described as an extended apprenticeship with a Yaqui Indian shaman named Don Juan Matus. His 10 books, etched in layer upon layer of psychological nuance and intrigue, became international best sellers translated into 17 languages and were credited with helping to usher in the New Age sensibility and reviving interest in Indian and Southwestern cultures.

Over the years, scholars and critics have debated whether Don Juan existed and whether the books were anthropology or fantasy, fact or fiction, distinctions which no doubt amused Mr. Castaneda.

Rather than respond, he lived in almost total anonymity, refusing to make public appearances, be photographed or tape-recorded. He continued to write up to his death and wanted his death to remain as private as his life, Ms. Drooz said. The Los Angeles Times reported his death yesterday after it was revealed by an Atlanta man who said he was Mr. Castaneda’s son. He said he heard about the death when he learned of probate proceedings.

But C. J. Castaneda, 36, who owns a coffee shop in suburban Atlanta, and his mother, Mr. Castaneda’s former wife, Margaret Runyan Castaneda, both say they are skeptical… and question why Mr. Castaneda’s death certificate said he was never married and why news of his death was kept from them.

Mrs. Castaneda, who said they were married from 1960 to 1973, said Mr. Castaneda was not her son’s biological father but he had the boy’s birth certificate changed legally to say that he was the boy’s father. Ms. Drooz said Carlos Castaneda was estranged from C. J. Castaneda, and the younger man was not his son.

If confusion follows in the wake of Mr. Castaneda’s death, it would be consistent with the story of his life.

Mr. Castaneda had said that he was born on Dec. 25, 1931, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and that Castaneda was an adopted surname. Immigration records indicate that he was born on Dec. 25, 1925, in Cajamarca, Peru, and Castaneda was his given name.

He came to the United States in 1951, according to the immigration records, and was an obscure graduate student in anthropology when he sent off a manuscript in 1967 to the University of California Press in Los Angeles. The book was released as ”The Teachings of Don Juan” in 1968.

After its paperback rights were resold, it became an international best seller. In the book, in encounters at once fanciful and intellectually and psychologically challenging, Don Juan instructs his disciple about becoming a ”man of knowledge’’…

…(His) books made Mr. Castaneda an international celebrity, and he was featured on the cover of Time. But many of his later books received cooler reviews. In The New York Times Book Review in 1988, Margot Adler described ”The Power of Silence: Further Lessons of Don Juan” as ”an unnecessarily cloudy pathway to the world of dreams and altered states.’’

NY Times, Peter Applebome, June 20, 1998

Regardless of whether Castaneda, and Don Juan’s wisdom, strike you as part of the psycho-babble and spiritual-babble of the 1960’s and 70’s in Western culture, or helped you profoundly in grounding yourself in a spiritual meaning, central, mysterious questions emerged from the Castaneda saga.

He was awarded a doctorate in anthropology from a serious institution for his “fieldwork,” supposedly, with the Yaqui natives of Sonora, and specifically with one Don Juan Matus. Years later, a consensus emerged that, at the very least, his fieldwork might have been embroidered, if not fabricated.

But not before his anthropology department basked, for years, in the popularity of having supported ground-breaking work in cultural anthropology, work that supposedly revealed, not even a thousand miles from Los Angeles as the crow flies, a rich repository of spiritual belief and tradition.

But was it fresh scholarship, or the work of a talented, fresh novelist?

Not to put too fine a point on it, the high priests of anthropology at UCLA may have gotten their academic fields confused. They awarded a doctorate to a gifted novelist, not a social scientist.

Fans of Castaneda so often ask, what does it matter? He helped me, and millions drink at the spring of a deeper spirituality, that’s what matters. Who cares what some stuffy old professors say about someone’s research methods–that’s the kind of bullshit that Don Juan taught us to rise above, anyway.

We appreciate where devotees might be coming from.

Nonetheless, we think that truth-in-advertising issues are more than a species of mystery, they’re a factor in life. If we respect those who’ve been enriched by Don Juan’s non-Western, non-linear thinking, we also ask respect for fact and honest reporting. Arguably, those are high spiritual values in their own right.

And his career was clouded almost from the beginning by the debate over whether Don Juan even existed or whether Castaneda was, as one critic put it, ”one of the great intellectual hoaxers” of all time.

Mr. Castaneda insisted that Don Juan was real. But others have said that, real or not, the books stand on their own both as windows onto the spiritual currents of the 60’s and as part of a long tradition of vivid intellectual and spiritual quests.

”The most important question we can ask is not, ‘Can Juan Matus be located in 1977 in Sonora, Mexico?’ ” wrote Sam Keen in Psychology Today. ”It is rather: ”What does Don Juan tell us about ourselves, about the millions in this country and abroad, who have read his words in 11 languages?’ As an archetypical hero, Don Juan may reveal to us something about the contours of the collective unconscious and the longings of our time.’’

NY Times, Peter Applebome, June 20, 1998

Do you agree with the venerable writer Keen (someone from a generation much earlier than the “flower children”) about what “the important question” is?

Do you agree about the core of the mystery?

WHAT WE KNOW, AND DON’T KNOW

To be clear, Castaneda was once interested in anthropology as the study of his life, both as an undergraduate and later for doctoral studies at UCLA, in California. That part’s not fiction, by any means.

Somewhere along the line, searching to learn a little more about Native Americans, he found himself in Yaqui territory in the Southwest, and supposedly met an elder of the Yaqui people, one Juan Matus. After a period of cultivating trust, and persuading Matus that he wouldn’t be wasting his time to mentor him, Carlos says he became an “apprentice” in shamanism. He spent long, quality hours and days with Matus, and took the journey to enlightenment, Yaqui style, under his guidance.

Later, when controversy arose, Castaneda was challenged to provide his original field notes, which he maintained had been lost, to flood damage. He was challenged as well to produce samples of the distinctive mushrooms he’d been writing about, but apparently began to ignore the communication from the expert he’d been in touch with.

In short, over time it became impossible to tell: what had been real anthropology, and what hadn’t? The original interest was surely sincere. And the fact that he’d spent some, at least some time interviewing Native elders about their system of beliefs, that was authentic as well.

So perhaps were a portion of the original writings. It’s been noted that the book that later became his first blockbuster was first sent off to his hometown academic press.

That’s where you send a manuscript with visions of academic recognition in mind. It’s not where you send a book to create a bestseller and earn millions in royalties.

Nonetheless, more than one graduate student has embellished his (non-existent) field notes. If you know the professors overseeing your research will never venture down the same dusty roads, to the middle of nowhere, that you claim to have travelled, why not? Any anthropological field experience could be a novel, not social science based on facts, if only the writer is gifted with a little creativity.

And creative he was.

Perhaps it’s when Carlos recognized that his generation was hungry for something fresh, a way of looking at the world that went beyond cold, linear calculations of the chances of nuclear conflict in a given year with a given enemy. That whatever enlightenment is, exactly, they craved it, and would sit, cross-legged for hours, at the feet of anyone who offered it. Perhaps that’s when he saw himself as so much, much more than just a anthropologist grinding through field studies, hoping to teach classes for a modest income one day.

What had begun as a quest for an advanced degree the easy way, by lively use of the imagination, turned into a fame he would never have imagined.

Castaneda was awarded his doctorate. His book was repackaged as a popular paperback. The publishers wanted more, always more. A second book followed, and a third and he became legend. As popular with youth as Vonnegut. As reclusive as Salinger. As inscrutable as Pynchon. And probably as wealthy as all three put together.

It took time for the community of anthropologists to realize they’d been had. Experts in the same Native American cultures gave him the benefit of the doubt, for a time.

Although this Don Matus doesn’t sound like a Yaqui shaman to us, maybe Carlos encountered a special guy, singular in that culture, with unique insights. Maybe he was disguising identities (not that uncommon in this work) to protect an informant who valued and needed his privacy.

It wasn’t the Yaqui who used peyote, in fact it was the Huichol, a different tribe of a different territory, where indeed peyote grew and was used for religious purposes. Well, maybe Castaneda changed tribal identities as well, going the extra mile to give these people their privacy and anonymity.

Maybe. Perhaps. Maybe. Excuses were made.

Then a deceased Huichol elder, a respected shaman, was identified as a likely model for the “Juan Matus” of legend. His widow was located and interviewed. Yes, she remembered this Carlos fellow, he hung around a bit. No, no he was hardly a shaman’s apprentice, by any stretch. He didn’t have the self-discipline for the practice, he just sat around and asked questions for a time. No, he achieved no real insight, nothing deep, into their culture.

In the end, for too many reasons to recount here, with too much evidence to ignore, it became all too clear.

This man, however bright and creative, was no honest anthropologist, or even honest spiritualist, or honest anything. At his core, he reminds us of P.T. Barnum, who knows how to pull all the elements of a good show together, who knows that people can easily be conned, and perhaps don’t even mind if the show is good enough. If it frees their minds, for a time.

Careful research has shown that every element of what “Don Juan” taught his “apprentice” was available in a book somewhere, right there in the library his fellow students used.

Perhaps he wasn’t so lazy, after all. His real work, while no one was looking, was old fashioned nose-in-a-book study and synthesis. He synthesized ideas around for millennia.

The more honest title of his first book would have been “Hidden Spiritual Currents: The Separate Reality You’ve Never Noticed in the Classic Texts.”

It would have been a much more honest book. It would have made him infinitely less money. But…for good or ill, it would have touched far fewer lives.

What we don’t know, will never know with certainty, is how much Castaneda actually learned from forays deep into the deserts of Native peoples, and how much from dusty old volumes on the shelf. Those facts have blown away, like the sand of those deserts, in the more than half a century gone by.

Does it really matter?

True believers in “a separate reality” will keep reminding us: what’s “true” is what resonates.

They believe: the great professor’s the one who influences his students, not the one who’s written a shelf full of dull books, read only by other professors.

It doesn’t matter that he pulled great insights together from far and wide, and put them in the mouth of a “shaman.” A shaman who supposedly danced around the Sonoran desert in summer, hopping like a sprite in the sunshine at one-hundred twenty degrees. Okay, perhaps that shaman never frolicked in the sunshine of midsummer, for the most obvious of reasons. He never really existed.

But that doesn’t matter, the insights do. The wisdom of the spirit shines through in his books, even hotter than those Sonoran summers…

Make of all that what you will.

In the next section, there’s the rest of Castaneda’s life to contemplate. There’s a lot we still don’t know there.

Oh, and if you have an hour, the documentary below from the BBC’s really interesting, the best of the YouTube offerings.

In spite of the title, they work hard to be fair. (This version has subtitles in the Cyrillic alphabet, we don’t know why, just ignore that.)

WHAT IN THE WORLD DOES IT ALL MEAN?

A mature, learned man named William Patterson can be seen on a long, high-quality video tape (YouTube) speaking about his journey with Carlos, or more nearly with his books and his “truths.” His audience are mature people, captured on camera with intimate clarity, perhaps of a median age of 50, and they are…rapt. They could be devout Catholics listening to the Pope, or Tibetan Buddists learning of teachings of the Dalai Lama. The whole phenomenon is striking.

Patterson makes some reference to the collapse of Castaneda’s credibility in most circles, but treats that lightly. He merely thinks Carlos would have been amused, delighted, at all the confusion and controversy, at how many angels try to dance on the head of his spiritual pin.

If reality is expanded, yet reduced, to intense beams of light, how much can the ephemeral twinking of something like a doctorate in anthropology really mean? How can you call a man’s statements untrue, if we’re all still grappling for that sense of what “truth” is?

And yet, at some point in his talk, Patterson asserts that you can’t “get at the truth through a lie.” A description, it would seem, of what Carlos attempted his entire life, but it’s not clear that Patterson caught the irony.

Carlos himself is not the only enigma here, rather the way countless people react to his life and writings offer up an enigma sandwich–several slices of cheese thick–as well.

And what do we really know of this phenomenal man?

His adopted son remembers, as a very young child, travels with him, down highways and byways, sometimes encountering Natives in his journeys. He remembers as well his father surrounded by boxes and boxes of documents. Notes from books? Notes from the field? We’ll never know.

As near as we can determine, the written works of Castaneda, are based on light experiences in the Southwestern US and Northwestern Mexico, with Natives, but on heavy time spent reading and borrowing ideas.

Don Juan Matus, as we know him, was much more fiction than fact.

(We’ll always wonder, when did it dawn on him that he was a decent anthropologist, but a born novelist? Why, and when did he move, surreptitiously, into his true calling?)

But what of the life and trajectory of Carlos Castaneda himself?

He lived out of the limelight, sometimes teaching some workshops related to his beliefs, but more and more, as the years went by, simply living off the grid, not easy for anyone to locate. No one was going to be able to do any “enthnographic research” on him, he was harder to track down than the proverbial Don Juan. Early on, he would give an occasional interview in his thickly accented English, to a a journalist who was still thoroughly credulous. On YouTube you can stream a long talk with Carlos and the noted writer Theodore Roszak.

As time went by and the questions would have been more and more skeptical, he simply ducked the challenge. If you wanted to put it charitably, he was too deeply involved in higher spiritual quests to wish to fritter time away answering unenlightened questions.

Spend even a short time in the study of Castanology, and you’ll soon encounter the phenomenon of Carlos and his…spiritual harem, for lack of a better term. The crowd of women, substantially more than men, that became cultish followers, often living in the same home, often sharing Carlos’s bed.

(Those who hated their influence on him—though it was more the other way around—dubbed them “the witches.” Then again, so did many in the inner circle.)

Couldn’t we simply interview those intimates, and construct his later years from their accounts? A few devotees are still heard from, some worshipful of their time with Castaneda, and many who feel they fell for a con. But learning from that closest cohort of women isn’t possible, they’re generally either deceased, or at least unaccounted for. As one Castaneda cynic put it, “four of the five women closest to him” died soon after he did.

One example of the ultimate devotee was Patricia Partin, an adopted daughter as well as lover—yes, you read that correctly. Of his women followers who are missing and unaccounted for, Partin is a special case in point, her bleached bones finally found in Death Valley. Speculation: she believed, as Carlos taught her, that in the raw desert you could cross over to the other, metaphysical side of consciousness. As she wandered the Valley, heat and dehydration took her down as they will any mortal soul. In time hikers found her bones, we may never know what happened to her spirit.

That’s a tragic, intriguing cult-mystery, all it’s own.

In the end, we’re left to construct impressions of what the older Carlos became. Consider this:

Certain types of famous writers become reclusive, shy of even being seen, photographed. They live cloistered in some corner that only a few intimates know about, with every possible detail of their lives screened from view. Check, that was Carlos.

Some celebrities stop seeking public adulation, preferring to spend time with a tight group of disciples, people available at their beck and call, people who hang upon their word as the word of God. Often, for a certain type of male, his admiring entourage is largely female. Check, that was Carlos.

Certain celebrities claim to have eschewed the shallow things in life, money and the material, casual sex, and the like, while indulging in private. Check, that was Carlos.

And savvy celebrities of the spirit, they know just how to scratch the spiritual itch of potential followers. They broker superpowers, sure roads to inner peace, nirvana, even ecstasy. Think about it, a method to achieve a spiritual magic–flying as the crow far above pedestrian cares, one of the oldest dreams of mankind. A metaphysical discipline leading to immortality, a life of utter serenity, without end, or rather ending in an eternal beam of consciousness.

The spiritual product for sale could hardly be more attractive, could it?

Are we left with an irony—that this most unique of individuals was also a sad stereotype? A “spiritual leader” who took not a vow not of poverty, but of wealth. A being who soared above mere worldly pleasures, and did so with a bevy of live-in lovers. A being who claimed to offer the highest, most etherial of truths, who couldn’t manage to meet the basic truths of his chosen profession. A being followed in hopes of receiving his great gift, which was often a gift of sheer abuse.

More than a decade ago, Salon weighed in with an interminable article: “The Dark Legacy of Carlos Castaneda.” It begins:

For fans of the literary con, it’s been a great few years. Currently, we have Richard Gere starring as Clifford Irving in “The Hoax,” a film about the ’70s novelist who penned a faux autobiography of Howard Hughes. We’ve had the unmasking of James Frey, JT LeRoy/Laura Albert and Harvard’s Kaavya Viswanathan, who plagiarized large chunks of her debut novel, forcing her publisher, Little, Brown and Co., to recall the book. Much has been written about the slippery boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, the publishing industry’s responsibility for distinguishing between the two, and the potential damage to readers. There’s been, however, hardly a mention of the 20th century’s most successful literary trickster: Carlos Castaneda.

Salon.com, Robert Marshall, April 12, 2007

Although this article’s so “thorough” it drops clarity and focus, those willing to hang in and read a long while learn about the gradual collapse of the hoax, and the miserable history of his cult. Cult, there’s no other word for it when the guru assumes demonic powers, and incites demonic acts. Take your pick from a hundred examples. Our “favorite:”

Carlos tells one young woman, for no reason that’s clear, to go home and whack her mother, a holocaust survivor, in the face. Which, fearing Carlos’s disapproval, she does.

What more do you really need to know?

MEMORIES OF “DON JUAN,” MEMORIES OF CASTANEDA

It has all the elements of other mysteries, rich What happened? and Whodunnit? questions. The grating questions of the missing women, the bones in the desert alone are compelling. A lot happened on a lot of levels to those who walked into the seductive, complex web of Carlos Casteneda.

But we consider it a mystery apart because Carlos’s writings, themselves, became a part of so many young readers in his era, and still today.

For so many, Casteneda represents more than a story of intrigue apart from us, he is us, part of our life, our growth.

Thus this section is devoted to memories of “Don Juan,” on all levels.

Do you have fresh information about some part of his life, or the aftermath?

Can you share how your journey of engaging life might have intersected with his works?