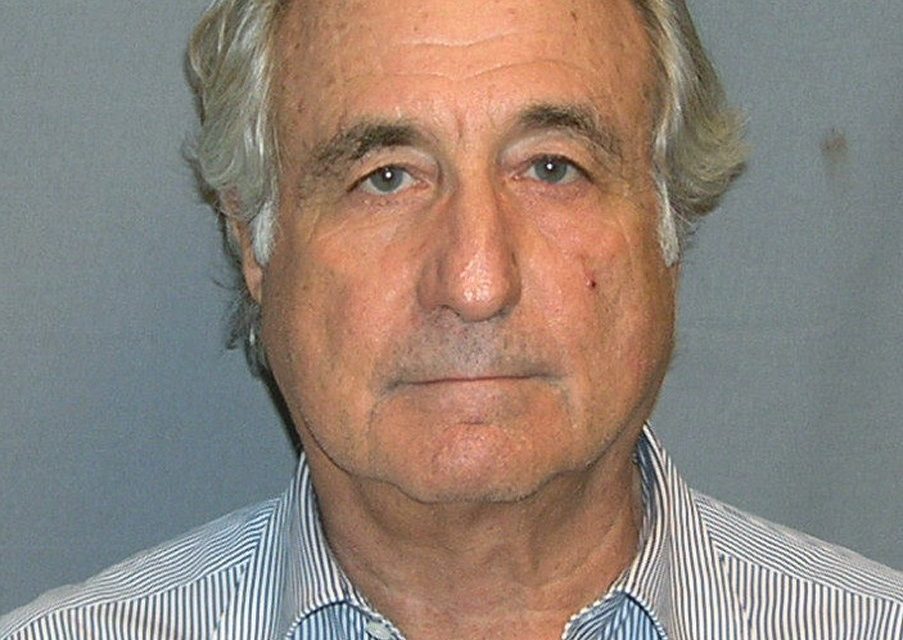

Bernie Madoff

There’s an old saying among professional swindlers that “you can’t con an honest man.” The “mark” was looking for something for nothing, or even running their own con, and just got taken in by a better one. A rationalization? Yes, but don’t be too quick to dismiss it. What type of person does fall for the too-good-to-be-true scenarios that con men concoct, and who enables them?

So what are we to make of Wall Street’s Bernie Madoff and his accomplices, and his victims? Sure, the crime was straightforward, no mystery really—rather the biggest pyramid fraud of all time, involving tens of billions of dollars of investors’ money going into illicit pockets. The grandfather of all Ponzi schemes was roundly sentenced to prison until the year 2159, when he would be 221 years old. But Madoff was merely the hub of a huge wheel of feeder funds, accountants, and regulators who all fiddled while lifetimes of savings burned. The public, and the courts, have asked the obvious question: what did these people know, and when did they know it? Over time, a few individuals who handled funds, or false documents, have followed Madoff to the Big House.

Yet the deepest mysteries of all still haunt the shadows of the disappearing billions-mysteries of greed, and the human psyche.

One talented financial analyst, Harry Markopolis, did everything short of run the streets naked with his hair on fire for years to call attention to the obvious fraud. He let regulators know, repeatedly, that the numbers simply didn’t add up. Why was he ignored by the Securities and Exchange Commission for so long? Why were individuals with enough business acumen to assemble large chunks of investment money naive enough to believe Madoff’s rosy investment reports? It’s easy to cast Bernie as the Devil Incarnate and give him 150 years in prison. We feel righteous, having decisively struck back at evil, in contrast to our honesty and innocence.

But the question should give us pause: was Madoff, contrary to the legend, conning a bunch of honest men and women? What will the money trail and the backstory tell us? Join us as we explore the question: how could Madoff have stolen so much from so many? We open the Madoff file.

WHAT’S SIXTY BILLION BETWEEN FRIENDS?

It was a very exclusive club, it seemed. You had to know someone, with connections, who could vouch for you and maybe, just maybe, get you accepted. So that you’d be one of the chosen ones, one of those allowed…to place your life’s savings into Bernie Maddoff’s Ponzi Scheme.

Now isn’t that classic! Not just everyone has this opportunity. But you do.

For one thing, you’re too busy mentally wondering Can I Get In? to be asking the better question–is this something legit that I want to get in to?

The snooty trappings of the deal alone should set off red flags. Just how did I get so lucky? Why should I make better passive returns on my money than everyone else, while I’m sitting around sipping martinis, or vigorously working at my golf game…out of a golf cart?

But not too many, early on or ever, wondered if their own judgment (or lethargy or greed) might be the problem. We so deeply want to believe, in our wisdom, in our deservedness.

There’s one such person born every minute. It keeps con men busy, just like drunk drivers fill up lawyer’s offices.

Bernie for his part, was extra smooth, ingenious even, and played the long con, keeping up and improving the appearances of the whole shebang over decades.

He got involved in charities. Nothing says “stable citizen, good guy, honest, generous soul” than someone who’s active in the local charity scene.

The larger charities have bank accounts, endowments. Where to invest them? You already know this fine fellow, Madoff, and he’s said to help people grow their money in very safe funds. I’ll ask Bernie.

And charities don’t withdraw much money, usually they leave the principal for the long haul. Now that’s just perfect, isn’t it, trusting clients who will feed significant capital into your coffers, and rarely ask for large chunks of it back?

But that wasn’t enough to feed the beast. Ponzi schemes always need fresh blood, infusions of new capital to cover the payouts that need to be made when someone cashes in. And besides, for those living large on the Ponzi money, they always prefer to live just a little larger. Which requires recruiting new money, all the time.

So Madoff made nice with hedge fund managers, knowing that those well capitalized financial institutions could be a bonanza. “Feeder funds,” where clients were directly dealing with some manager they knew, but indirectly feeding cash into Bernie’s scheme, became increasingly common.

And you can rest assured that the managers were well compensated, generous fees for steering money Madoff’s way. And these were years, the 80’s and 90’s and beyond, of financial growth, and runaway greed in the world of money. Some said it became a sort of “Lord of the Flies,” Wall Street version.

So Madoff had a perpetual motion money machine, such a slick set-up, except… If enough people at one time want their money back it collapses. That’s precisely what happened in the severe recession era starting in 2007. To cover losses elsewhere, investors reluctantly cashed out of Madoff’s fund.

Except that he hadn’t grown that money, he’d spent it. There’s wasn’t enough to go around and sustain the fiction.

Madoff was cooked. Madoff confessed first to his sons, who maintained they were astounded at the admission. By December 10, 2008, they were telling authorities what they knew, and Madoff was arrested soon thereafter.

The aftermath was a s*#tstorm, of epic proportions, for weeks to come. But the unraveling took its toll for years.

Sadly, the scandal even produced suicides.

The frenchman and financier René-Thierry Magon de La Villehuchet, said to be an old European gentleman of the finest order, slit his wrists when he realized how many people he’d steered toward financial destruction with Madoff. Charles Murphy of Wall Street, a respected graduate of Harvard Law School, leapt from the 24th floor of a building to his death. A retired, decorated veteran, William Foxton, killed himself after losing his life savings. And most poignantly of all, Bernie’s son Mark Madoff hanged himself two years after the outbreak of the scandal.

Those are only the headlines, the suicides. For anyone, anywhere in Madoff’s financial orbit, the fallout has been something they’ll always remember.

THE CONFESSION, THE QUESTIONS

Thus in December of 2008, the dam broke, and all hell broke loose as well. The losses were not really 60 plus billion–that wealth had only been fabricated, on paper, anyway–but some 20 billion cold, hard dollars had been entrusted to Madoff’s fund. And investors woke to the realization that almost all of that was gone, smoke in the air.

They might never see their family nest egg returned.

Among those reeling from the news, numerous bankers and fund managers, from all over the world, who’d passed clients’ funds on to Madoff, for all that sure growth (and finders-fees for themselves). Most clients may have been aware of where their funds ended up, but many weren’t. It was up to their local money managers to give them the news about their life’s savings that December. Merry Christmas.

Who, besides Madoff, was responsible for this fiasco?

There were the clerical and accounting people who handled the fictitious reports (some of whom are in jail). There was much made of the small banking firm that handled big money for Bernie. Wouldn’t they be a little bit curious about this client, these huge sums of money often just sitting there, rather than active as investments somewhere?

What’s remarkable is how little curiosity people have when they’re handed stacks of money. With rare exceptions, they take it with a nod and move on. Bankers. Feeder fund managers, offered generous fees.

Everyone’s interests were aligned, it seems, except for the poor “marks” that were forking over money, and watching it “grow” in the fanciful reports they received.

In that sense, Madoff was no lone ranger of financial evil, he was the hub of an institution. He needed a host of enablers, and not just on the clerical side. There aren’t the hours in a day for one person to cultivate that many investors.

So, how much culpability do the fund managers have, those who channeled lots of cash in Madoff’s direction? Many of them also had personal funds with Madoff, and took a hit with everyone else. Many did not.

But consider: by definition, these fund managers, to be worthy of the name, had the credentials of financial education, and experience, and supposedly savvy. Yet they asked no questions about a fund that supposedly grew at a steady one per cent per month, whatever the financial weather.

As whistleblower Harry Markopolis observed, there were only three explanations for that kind of performance: the greatest genius ever to grace Wall Street, insider trading, or a Ponzi scheme. The first is highly unlikely, the other two highly illegal.

Wouldn’t that make financial professionals just a little wary, and apt to ask questions? But very few did.

CAN YOU CON AN HONEST MAN?

In our introduction, we spoke about the old saw that you can’t con an honest man. James Walsh even has a recent book out, an exploration of the Ponzi scheme and its practitioners, whose titles begins with “You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man.”

But are we being too hard on the “marks,” are we blaming the victim here? Perhaps yes, and also no. Let’s discuss.

Naturally, we all ache for the charities that took a hit. Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel’s foundation, and it’s losses to Madoff, makes for a heart-rending photo op. We don’t know the inside story of who from Wiesel’s group placed the money with Bernie, who was supposed to have checked it all out.

And we have a soft spot for busy, hard-working people who might not know the reasonable limits of investing success, that is, know when the returns are simply too good to be true.

Actors Kevin Bacon and wife Kyra Sedgwick presumably have a plate piled high, busy careers and travel schedules, a long-lasting Hollywood marriage and kids to raise. If they didn’t look the gift horse of Madoff’s returns too closely in the mouth, we cut them some slack. We figure it’s not lack of intelligence or integrity, it’s lack of time due to lives focused elsewhere.

Who’s to say who had the time to perform due diligence? But that phrase, originally from the legal world, cuts to the heart of the matter. Due diligence assumes you find the time, take the time, or consult the expertise to make good decisions in your sphere of responsibility. If you don’t care about your discretionary couple of million parked in a fund somewhere (and, of course, everyone does care) then go ahead and flip a coin over your decision.

If you do consider your money a matter of high stakes, then do you really have an excuse? And let’s be clear, Bernie’s clients, either directly or through feeder funds, were generally the wealthy. This was not the poor neighborhood Credit Union, where folks might proudly have a few thousand dollars in their savings account.

These folks had placed millions, and thus the question: How can you be savvy enough to amass a good-sized pile of money, and so naive as to have never heard the phrase “too good to be true”? That’s Finance 101, really Life 101, and everyone’s been exposed to the warning, if they care to pay attention.

This guy’s fund makes steady money, whether the market’s up, or it’s down. Can he fly without wings as well, walk on water? In other words, just how the heck does he do that? For a guy with his long history, and elite connections to the Street, we wouldn’t have imagined a Ponzi structure either.

We’d have imagined some species of “insider trading” –making money on inside information you shouldn’t have, at least shouldn’t play the market with. The other explanation: Bernie and his traders have come up with a secret trading code, have developed a new analytical tool that enables them to make money, in all market conditions, when no one else has.

That’s possible, Einstein’s breakthroughs, obviously, were possible.

But with tens of thousands of the best, brightest analytical minds working on just that challenge, for a century now, just how likely is it that Bernie’s cooked up a legitimate secret sauce?

How plausible is that explanation, compared to say, insider trading based on his lifetime of contacts?

Anyone doing true due diligence on the matter would have asked themselves that hard question.

It shouldn’t have taken Harry Markopolis, and his high level skills at financial analysis, to see through Madoff.

His sons worked on a different floor, a different division, away from the scam entirely. The story is they knew nothing, were stunned when the father came clean to them, and went to authorities straight away. But Sherlock still has questions.

The sons were brought up on Wall Street wisdom. Did they never ask, Dad what’s this secret formula that no one else has, and if so, what was the answer? And many assume Ruth Madoff knew, although she and Bernie swear, no she didn’t.

In she end, she lost as much as any “victim.” Her two sons are dead, one from suicide induced by the scandal, the other from cancer two years later. Her husband may as well be dead, and so is her reputation or dignity anywhere in society. She’s lives on in quiet anonymity, as best she can.

The stories of victims could fill volumes, themselves.

Let’s look at a couple of remarkable cases. From an article from the UK, right after this all broke:

A 95-year-old Boston clothing tycoon, Carl Shapiro, looks set to be the biggest single victim of Bernard Madoff’s fund management scam by losing up to $545m (£357m) at the hands of the Wall Street fraudster.

A respected philanthropist, Shapiro entrusted much of his wealth to Madoff and had $400m of his own money in the disgraced financier’s firm, plus $145m from his family’s charitable foundation.

HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland, Banco Santander, scores of hedge funds and many Jewish charities are nursing a big exposure to what has become known as the world’s largest Ponzi scheme.

But Shapiro’s loss is the greatest disclosed by a private individual so far. The elderly entrepreneur made his fortune by founding a womenswear label, Kay Windsor, which is still known in fashion circles for its vintage floral dresses despite being defunct since the early 1980s. He sold the business to Vanity Fair in 1971.

According to the Boston Globe newspaper, Shapiro’s family are friends and neighbours of Madoff in the exclusive Florida enclave of Palm Beach. Shapiro said he was “stunned and saddened” to learn of the allegations surrounding Madoff.

The Guardian, Dec. 16, 2008

A neighbor, a friend of Madoff’s for half a century, baldly burned. That’s a long time to know someone, time for trust to settle in. But shouldn’t a ninety-five year old have also learned life’s basic lessons? Seven, eight decades of business experience, and Mr. Shapiro can’t look at financial reports and wonder if something’s up? We feel for the elderly gentleman, but he should have been long past the age of financial innocence.

Then there’s the complex matter of New York Mets owner Fred Wilpon. His relationship with Madoff was long-term, involving serious dollars, serious implications.

Why were the Mets so heavily invested with Bernie Madoff?

The Mets and their owners were so addicted to the Madoff gravy train that they had nearly 500 accounts with him. The basic reason is that Madoff gave the Mets three things all investors want:

1) High returns—The Wilpons were getting (fictitious) annual returns of 12-18% from their investments with Madoff.

2) Consistent returns—Madoff never failed to produce double-digit returns, even for a single year of their multiple-decade relationship. These consistently high returns are a big part of the reason the Mets made deferred-compensation agreements with Bobby Bonilla and others; they figured that instead of paying the players while they were playing, the Mets would give that money to Madoff. Then, by the time the deferred compensation was due, the investment would have grown enough to easily pay off the promised compensation with money to spare.

3) Liquidity—The nature of the Wilpons’ relationship with Madoff allowed them to invest their money, profit from it, and then turn around and reinvest both the principal and the profit to really accelerate their gains. They felt comfortable operating like this because they knew that whenever they needed a little extra cash, they could withdraw it from their Madoff accounts with no problem.

amazinavenue.com, March 30, 2015

This excerpt from a “primer” on the issue goes on a while, complicated enough to make brain cells ache. But we’ll boil down the gist for you:

Yes, Wilpon was another “victim” of Madoff, left with some empty accounts when Madoff went belly up.

But, over the years, the Mets owner had also cashed in a lot of Madoff “earnings,” now considered bogus earnings by the government. In that sense, he’s an unwitting partner in fraud.

He’s someone who got his hands on money newly committed by other suckers, that is, investors, but paid out to Wilpon upon request to sustain that fiction that your accounts have grown, and you can cash them in any time.

Think about it, it’s an interesting brain-teaser for regulators. What do you do with someone who cashed out his account or accounts with Madoff, but ended up with money not earned in legitimate market conduct. The money instead came from other poor souls, that’s what a Ponzi scheme is. Do you use legal tools to pry that money, minus the original principal, loose from investors who think they “earned it,” to redistribute back to victims left high and dry?

The money might have tripled, quadrupled, over a couple of decades of its fictional growth. Do you leave it with the client who was lucky or prescient (or suspicious) enough to get out, or send it back to others?

Wilpon’s relationship to Madoff, so many accounts over so many years, took a herd of CPA’s to untangle, but at the end of the day: He gets some consideration for the money he lost with Bernie, but it’s offset by the money he gained by Bernie’s fraud. At the time the article was written, the Mets were slated to owe about $29 million back to the compensation fund, out of well over $150 million said to have been cashed in over the years.

The unlikely relationship of Madoff and a Major League baseball team has a thousand more wrinkles–it could be a book in itself.

But beyond the complex moral and financial math, the question leaps out again. Here’s a guy who’s in a rarefied height of the business world–there’s such a limited number of top professional sports franchises. Owning one has replaced polo as the sport of billionaires.

What’s a businessman of that caliber, that experience, doing in accounts that always pay back over 12% per year? Should we have any sympathy for him, biting on the rusty old hook of “too good to be true?”

It really makes you wonder if he’s so innocent at all. Might he have been along for the ride with Bernie, explicitly or subconsciously, and just been caught by surprise, standing in the musical chairs game, when the end came so suddenly?

He’ll never be jailed. But, should he be?

BERNIE MADOFF, LESSONS LEARNED

“The question of when it became a fraud is fundamental to the Bernie Madoff mystery,” said financial writer Diana Henriques of the New York Times.

Bernie was collecting people’s money, to put in funds, since he was a very young Wall Street up-and-comer. It isn’t clear exactly when, and exactly why, he turned a promising conventional career into such an infamous one.

Given that the early investors all got their money back on request, we don’t know at that point if they were paid out from Ponzi-investment, or the real thing, back in the day. It would be interesting to dig, and figure out just how far back his first scam took place. Did he get away with it all for 20 years, 30, 40?

But what’s the lesson? That we can’t restrain ourselves from believing that we’ve stumbled on a pot of gold, any more than we can restrain ourselves from that potato chip? We know better, but…

We usually confine our links to videos to short ones, valuing your time.

But we must recommend this three-quarter-hour long review of Madoff’s crime. It’s well done, and it hits so many nooks and crannies of the psychology of the con, it’s worth hanging in for the duration.

We want to consecrate the rest of this space to those who have something to add about the Madoff phenomenon.

Regular MOMystery contributors. Readers who write in.

Perhaps, even victim-investors will share perspective here. There’s more story to be told.