J. Edgar Hoover

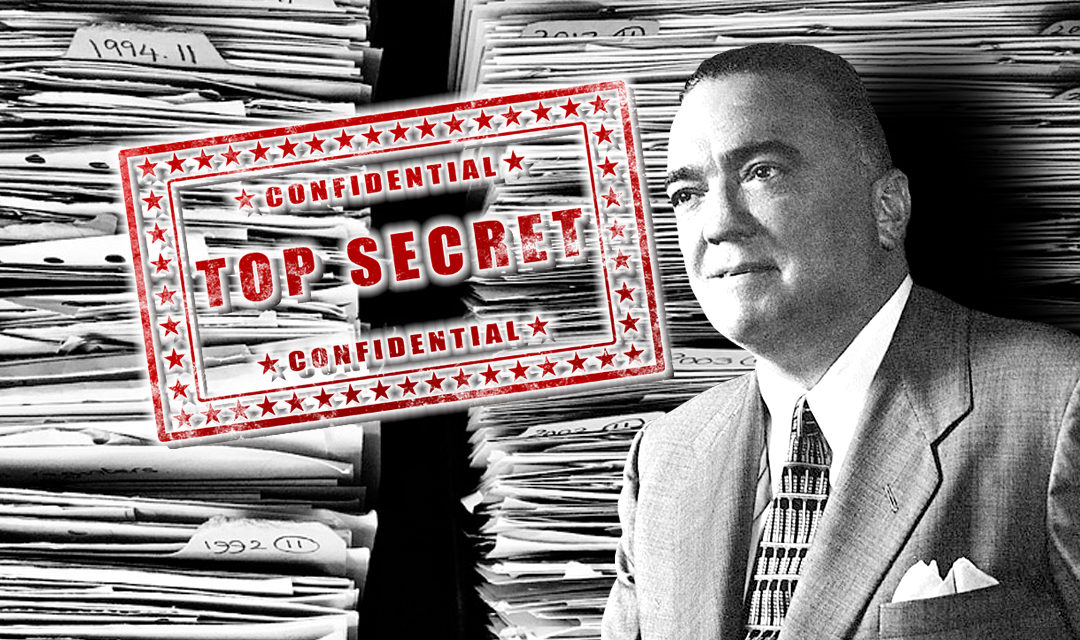

These are the so-called secret files that J. Edgar Hoover kept on anyone with the power to do him favors, or do him ill, a huge swath of America’s power structure. All serious biographers of Hoover recognize the existence of the files, a sort of “second set of books” at the top of American law enforcement. The files were culled through and illegally destroyed, it appears, in the weeks after Hoover’s death by trusted associates, especially his life-long secretary, Helen Gandy.

Because the documents were sent to the shredder, we will never know precisely what was in them, but surely enough scandal to keep a tabloid paper filled for several years. The historical record indicates that the new, incoming Bureau director, L. Patrick Gray, asked about the alternative files but was outmaneuvered by FBI insiders. Did authorities really want to find those files? Is there more we can learn about, or learn from, perhaps the largest cache of secret police files ever assembled on our continent?

The Secret Files

For all the files treated under the section “Corruption and Conspiracy,” some words of introduction are in order:Let’s be clear: MindOverMystery is a serious mystery research entity. The last thing we are is a bunch of “conspiracy theorists,” whatever that tired phrase means.

Most of the people who see all government, everywhere, as an evil black hole trying to swallow us…those people are often unwell.

They’re handicapped, if not psychologically, in their lack of worldly experience, in how systems and social groups really function. They often have no direct experience in making elaborate systems work, in seeing the big, multi-faceted picture. And a tangled world, ever more subtle, is upon us. Quoting the former President of the University of Hawaii, Harland Cleveland, “complexity has a bright future.”

So, you guys who have nowhere to live but their grandmother’s basement, and nothing to do but read sensational “facts” on-line and spin them into overreaching theories–you won’t be happy with this website. Look elsewhere. If you think the Sandy Hook shootings were orchestrated by Martin Scorsese directing a cast of hundreds to stage a fake media event, please don’t waste our time even writing in.

So, you guys who have nowhere to live but their grandmother’s basement, and nothing to do but read sensational “facts” on-line and spin them into overreaching theories–you won’t be happy with this website. Look elsewhere. If you think the Sandy Hook shootings were orchestrated by Martin Scorsese directing a cast of hundreds to stage a fake media event, please don’t waste our time even writing in.

But don’t worry, there’s plenty of other folks who dropped out of Logic 101 on the first day, wearing a tin-foil hat just like yours. You guys can keep each other entertained on-line, forever.

That’s a tart assessment of some folks out there, but necessary. We didn’t mean to be nasty, just very clear. Sherlock was only a fictional character, and even he got it. Attention to facts and detail, and good deductive reasoning will take you a long, long way in getting to the bottom of some things.

That said, some skeptics lean a little too far the other way. Anything not apparent on the surface, or sustained by the official line of some agency, gets laughed at, waved away dismissively as a silly “conspiracy theory.” The phrase itself is dumb, overused, and distracting from intelligent dialogue. It should never have taken over the language of investigation.

We blame the tin-foil hat guys for the popularity of that phrase, because they often are “conspiracy nuts,” driven for some reason to see conspiracy under every pebble on the beach.

But the rest of us can have an intelligent dialogue, without the use of that phrase.

Dr. Kevin deLa Plante, former chair of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Iowa State University, for years has served as a leading educator in the field of rational or logical thinking, often called “critical thinking.” (His excellent, abundant Podcasts are easy to locate.) One of things he’s had to encounter are the complex historical cases that spawn a bevy of theories, some involving conspiracy.

Dr. deLa Plante reminds us of something basic: any event involving more than person in planning and execution, or coverup, is a conspiracy, by definition. A guy robbing a bank all by his lonesome, no, but one guy and his getaway driver, that’s a conspiracy. A bookkeeper managing to steal money all by herself, no, but with a partner in the embezzlement, conspiracy.

Many if not most criminal prosecutions, and many statutes at state and federal levels (RICO statutes in the U.S. and a host of others), involve conspiracy–simply the coordinated actions of more than one person.

And of the so-called “conspiracy theories” out there, deLa Plante says, if we knew all the facts, some would probably prove to be true. Others would register as false upon close examination. God and and Devil are in the details, and in the logical thinking we apply to them.

So it’s very silly to talk about “conspiracy theories” with a negative twist.

If you think a theory is unsupported (by evidence or logic), or overreaching, or driven by stark, deluded paranoia, then say so. Call it an “unsupported theory” or “overreaching theory” or even “paranoid theory” if you have some basis for that.

If you it a “conspiracy theory” in a nasty way, you only reveal you haven’t thought out words and their meaning very well.

One further disclaimer.

In analyzing mysteries centering around political figures, scandal, and corruption, we know we stray into delicate territory.

To be clear, we choose and analyze mysteries with no conscious political bias whatever. We do mystery, not politics.

We don’t give any money to, or support, any party or partisan effort. We’re non-partisan, we don’t have a “progressive” or “conservative” agenda, a Republican or a Democratic leaning in the United States context. For issues in England, we lean neither Labor nor Conservative.

You get the idea. We’re too busy trying to find facts, context, and get to the logic and big picture of a mystery to be led astray by political thoughts. We don’t ask the political affiliations, if any, of our contributing writers and thinkers. They understand that when they walk through the portal of mystery, there’s no room for political bias of any sort.

We hope if you spend time with us, you’ll agree we strive for objectivity, as professional mystery analysts.

On to the matter of “J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret Files.” Why the topic, what’s on our minds?

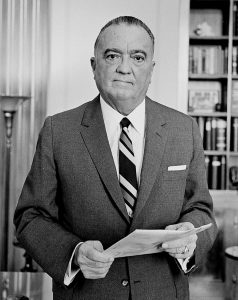

Since Hoover’s death on May 2 of 1972, a steady drumbeat of full, well-researched books, not to mention a thousand articles and reports, have explored his amazing tenure at the FBI.

Those born after 1960 or so may find it hard to fully grasp….So we offer some highlights to help comprehend:

- Hoover went so far back with the agency, as a very young man running a young, emerging federal police, that in effect he was the FBI. Nearly fifty years in office. The institution was him, and he was the institution.

- Hoover rode the wave of new technologies, fingerprints and forensic science and the like, and receives credit for having centralized data on crime, and for having brought law enforcement fully into the 20th century

- Hoover ruled a growing organization with an iron hand all those years. To fall out of favor with “the Director” was to be exiled to law enforcement Siberia. You worshiped the Director, or you were gone. Naturally, he was showered with birthday gifts from agents who’d only met him once, if at all.

- Hoover early on grew his power in the traditional, effective circular manner–his growing powers and fame allowed him increasingly wide contacts and political influence, and those allies and information sources allowed him to keep enhancing his power. On the organization chart, he was two huge notches down from whichever President was in office. (The President appoints an Attorney General, who in turn supervises the Director of the FBI.) But in practice his powers grew so formidable that almost all Presidents treated him with kid gloves, gingerly, with great respect. Especially the later Chief Executives, from JFK, through Johnson to Nixon, saw the need to end his long run at the FBI, but didn’t quite dare pull the trigger to fire him. He died abruptly of a heart attack on Richard Nixon’s watch in 1972.

- Why was everyone scared of this guy? Washington insiders knew that his growing, coast-to-coast team of investigators did more than just hunt down kidnappers and bank robbers. They did more than keep track of Communists and subversives. They also opened a file on, and spied on, anyone the Director wanted them to. Apparently, that was anyone who had influence in the U.S. or might one day, a long list.

- So, all those years, we paid our tax dollars to have ourselves surveilled. Sometimes agents just followed, watched, followed some more, generated reports and more reports. But phones were tapped and rooms were bugged, as well. The FBI those years was not scrupulous about presumptions of innocence, or rights to privacy.

- FOIA requests in recent years confirm the extent of surveillance of non-criminals. The FBI even bugged the activities of Eleanor Roosevelt when she was First Lady. Perhaps co-incidentally, or not, she’s said to have complained to FDR that the Bureau was essentially an “American Gestapo.” The President, however, was not inclined to ride Hoover too hard, because the FBI was providing the Chief Executive with valuable political intel. Hoover knew which side his bread was buttered on.

- At the time of his abrupt death, the agency was thrown into turmoil. Hoover’s long time second-in-command and alleged lover, Clyde Tolsen, wandered around looking like a concentration camp survivor. An institution with continent-wide, in some ways world-wide reach suddenly had it’s spine yanked out of it. FBI culture survived, but evolved in many ways in the next twenty years.

- After Hoover’s death, the powers-that-be made some changes intended to curb abuses in the future, such as limitations on the time any one individual can serve as FBI director.

- The huge Department of Justice FBI Building in Washington bears Hoover’s name, although almost everyone now classifies his time as Director as filled with excesses, if not downright abuses. But in politics many cans of worms are best left with the lid on. Many political leaders believe that this is one of them.

In the following brief sections we’ll explore the context of Hoover’s years and surveillance empire, and a few examples.

THE TIMES AND THE CONTEXT

As Hoover expert Professor Richard Gid Powers has noted, all great careers are a mixture of ability and competence, combined with huge doses of blind good luck. Perhaps Hoover was able enough to deserve some credit for his tenure and rise, but mostly he was in the right place at the right time, and grew his power by brutal methods.

From the Red Scare of the 1920’s to the gangster-ridden thirties, the times themselves were ready made for the emergence of a national police force, and Hoover was there to grow a tiny agency, over time, into a big one. (In this century the FBI annual budget has swelled into the neighborhood of over $10 billion.)

At the time of the Red Scare, much of the public came to believe that subversives of one stripe or another were a severe threat to the homeland. Communists, anarchists, you name it. The emerging federal agency that became the FBI was there to help–round up Commies, send anarchists, like the infamous immigrant Emma Goldman, packing back to where they came from.

And when bank robbers like John Dillinger seemed untouchable, the FBI was there in Chicago in 1934 to bring him down. It did seem like the Dillingers of the time were out of control, but the “G Men” won in the end. Hoover considered his death mask a trophy, and kept it in his office.

Yet it’s almost unanimous: under Hoover the agency went far beyond it’s original charge, and far beyond the scope of proper law enforcement.

In the end, according to the prominent politician Walt Mondale of Minnesota, Hoover evolved from a lawman to more of a “political enforcer.” He didn’t just pursue criminality, he pursued and persecuted “ideas,” the ones he didn’t agree with. And that, according to Mondale, is “dangerous” in a democracy.

More than one powerful and well-informed Washington insider, with Senator Estes Kefauver as only an example, came to understand the awesome power yielded by the Director. “He’s more powerful than the President,” Kefauver warned. Many others, over the years, seconded his opinion.

But others disagree, or at least see reality in somewhat gentler shades. Some of his former top employees, for example William C. Sullivan, serve as the source of much of the scandal that’s accrued over the years. But others, such as Cartha DeLoach, who served the inner circle and as a PR man for the Bureau, maintain that shallow myth, and not much truth, emerge from all these Hoover stories. There are certainly lots of stories.

In 2011, Clint Eastwood directed the biopic “J. Edgar,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Good entertainment, but was it realistic, true to the historical record?

Below, Robert Siegel of NPR and Beverly Gage, historian and Hoover expert from Yale University, discuss the film, and a few examples of the accuracy of it’s portrayal.

SIEGEL: We’re not interested so much in the odd factual error here as in the general truthfulness of the portrayal. Does this movie present a J. Edgar Hoover whom you understand as J. Edgar Hoover?

GAGE: The movie fictionalizes a lot of scenes as any Hollywood film about a historical figure does, but I think, overall, it actually does a pretty good job of conveying the big picture of Hoover’s life, some of the biggest themes and the biggest questions we still have about Hoover.

SIEGEL: Well, first, professionally, we heard him being the disciplinarian and the stickler at the bureau. Does it give a balanced picture of his leadership of the FBI?

GAGE: I think it’s hard for people today who have over the past 40 years sort of seen Hoover largely as a villain to remember that he did come to office, in fact, as a reformer. He came in to clean it up, to professionalize it….the bureau was going to be different from the sort of corrupt low-brow police (people expected). (That) was really Hoover’s identifying factor for many, many years of his early career.

NPR, December 28, 2011

And there’s the question of everyone’s interest, if only their prurient interest, in Hoover’s sex life or lack thereof. Although he persecuted gays in his time, was he gay himself? The film at least hints at answers.

SIEGEL: Now, the screenwriter, Dustin Lance Black, is openly gay. He’s the man who wrote “Milk,” and he treats the Hoover-Tolson relationship as unquestionably romantic and physical, at least so far as kissing and embracing go. Is “J. Edgar” the movie stating the obvious here or stretching the evidence?

GAGE: Well, this is one of these very, very tantalizing historical relationships that people have been trying to get to the bottom of for decades. It’s certainly true, as the movie says, that they had this very intense social partnership for 40 years, which is to say they did have dinner together. They went to nightclubs together. They were treated more or less as a couple, almost as a married couple. What we don’t really know is what went on between the two of them when they were having private conversations.

So most of the movie, when we see these scenes around the breakfast table or these sort of intimate conversations in other places, that’s all kind of fictionalized based on what we do know, which is that there was this very deep partnership. And it doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to look at two men who really didn’t date women, who spent most of their lives together and imagine that they might have been in love with each other.

NPR, December 28, 2011

There’s also a scene in which Hoover is seen leaving a memoir behind.

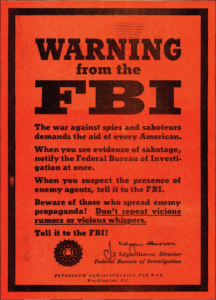

GAGE: He didn’t ever have the sort of formal situation that you see in the movie where he was dictating a memoir to a series of young agents, and that that is the official record of the FBI. But what we was very famous for and very successful at was having an enormous propaganda division at the FBI that both glorified the FBI, sent out Hoover’s own kind of political messages about communists, about personal morality. And that also glorified J. Edgar Hoover, and that was one of his really singular accomplishments at the FBI.

NPR, December 28, 2011

All of those things, Hoover was. A lawyer, an effective fighter of subversives, a modernizing force in law enforcement, a friend to Presidents and the rich and famous, a dapper dresser, a shameless self-promoter.

And arising from all those years, as well, troves of information on almost all of America’s power brokers.

Should those files have even existed? How “secret” were they?

THE DANGER AND THE DAMAGE

But rest assured we only quote passages we believe to be corroborated elsewhere. And in the field of Hoover-studies, corroboration grows steadily, like a new pine forest–articles and books and studies and quotes, in droves.

We quote here from Curt Gentry’s “J. Edgar Hoover, The Man and the Secrets,” an extensive book that tells the tale in clear, compelling, readable fashion.

“To Hoover, as to Machiavelli, knowledge was power, and the chief source of that knowledge was, and remained throughout his long tenure as director of the FBI, his informants, who infiltrated every part of the federal government.

Name a bureau or department or regulatory agency or office, William Sullivan once said, and ‘and we had one or more informants in it, usually a lot more.’

Curt Gentry, J. Edgar. Hoover, p. 412 (trade paper edition)

Informants weren’t hard to come by if the FBI was willing to play hard-ball, for example homosexuals were pariahs at the time, and the Bureau would, not to put too fine a point on it, blackmail them.

Gentry’s book, taken page-for-page or as a whole, makes for a jaw-dropping read. It lends itself to clichéd exclamations–“if even a quarter of what’s printed there is true, it’s a scandal and outrage of the highest order!” the reader wants to shout. But how do we know what percentage is right, absolutely the way it was?

History and mystery rely on sources, credibility, corroboration. True, if you look at Gentry’s extensive footnotes, you’ll see some of them sourced to “former Hoover aide” or “former administrative assistant,” with no name attached. Why, two decades after J. Edgar was safely in the grave, and the FBI (in many ways) reforming, couldn’t their names be used? Some folks will only speak without attribution, from whatever sense of caution. And of 37 notes attached to a sample chapter, only 3 were attributed anonymously.

Of the others, some were in effect re-quotes from other muckraking books. That, though, doesn’t necessarily make them invalid. We have to judge source by source, context by context. In the end, we strongly suspect that a whole lot more than a quarter of Gentry’s stark tales and conclusions about the FBI of that era are true, probably a very strong majority of the assertions. We leave it to you, if you ever engage with the book, to judge what’s seems solid, what might be iffy.

And what are we to make of inside sources with such divergent axes to grind? William C. Sullivan, quoted above, once number three man of the whole shebang, was until his death (by hunting accident) a rambunctious source, a delicious smorgasbord of juicy and generally unflattering stories about The Director. Sullivan was finally fired for some real or imagined transgression or other, hardly unusual in Hoover-world. Thus his kiss-and- tell exposés of his time at the Bureau could be labeled as sour grapes, or sensationalism, or both. Cartha DeLoach, another top man and would-be Director, and finally retiree from the FBI wrote his own account of those years, to dispel all the false tales told by the William Sullivans out there. So much nonsense out there, he maintains, but I can give you the honest scoop.

We watched DeLoach sit for an hour-long interview about his memoirs, and some of what he said rang true. But lots of his statements strained credulity–as he asserted again and again that the Bureau did things by the book. And those thousand tales out there, from a thousand sources, are all mistaken or dishonest? Come now.

And he finally lost much of his credibility by maintaining that the Bureau of the 1960’s was fully above racism, that blacks and whites and their issues were treated totally without prejudice. Seriously? Two of the Senior Editors of this website are from the South, and knew it well in the old days. The occasional white man without prejudice existed in that time, but not the kind of guys attracted to Hoover and the Bureau, law degrees or not.

DeLoach ends up a bit pathetic, still doing PR for his old agency, perhaps wanting to be associated in retrospect with a finer organization. He would have done better to admit the full truth, but then explain the positives as well, in context.

Back to the bitter pill that was the political bite of an organization funded, supposedly, to only investigate and enforce federal law.

(On the famed matter of inappropriate surveillance, files, and attempted intimidation of Dr. Martin Luther King, Cartha DeLoach concedes it happened–but it was all William Sullivan’s fault, completely his operation. Again, you shake your head as DeLoach insults your intelligence.)

We could quote Gentry all day and night with one interesting paragraph after another, but perhaps another couple of quotes will do.

“Favored politicians were warned who their opponents would be, what backing they had, and what skeletons might be hidden in their closets. In some cases, they were elected with the FBI’s help. Impressed with a young Republican congressional hopeful in Michigan, the Bureau in 1946 arranged support for Gerald Ford, who expressed his thanks in his maiden speech by asking for a pay raise for J. Edgar Hoover.”

Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover, p. 412 (trade paper edition)

Yes, Hoover kept extensive files on an extensive list, but he didn’t really afford the right of files and exposé to others, unless it was totally flattering to him.

They relate the story of retired Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and his future memoirs, parked at the time in the National Archives. Hoover got wind he intended to publish them.

‘It was a very covert operation,’ a senior agent who headed the raiding party has recalled, ‘damn covert. There were five of us, and we were all sworn to absolute secrecy….we’d go in (an out-of-the-way room at the National Archives) at different times so no one would know five agents were in that room. And we were the only ones who had a key.’

Their only equipment, which they carried in their briefcases, was scissors.”

Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover, p. 412 (trade paper edition)

They were cutting out, right and left, anything in those papers unflattering to Hoover, or the Bureau.

Senator John McClellan grilling Hoover before a Senate Committee has entered into our lore, McClellan asking Hoover if he’s ever arrested anyone, which of course he hadn’t (the FBI didn’t even have that authority in it’s early years). What’s often forgotten is the Senator’s basic beef, that the Bureau seemed to have a heck-of-a publicity budget, and an overly vigorous PR machine. The FBI, among other things, hawked comic books…yes, comic books set in a mythical FBI-land with their own superman, J. Edgar Hoover of course.

Hoover would make nice with a President, all the while fattening up the file he had on the man. He would enjoy meeting Marilyn Monroe with a huge grin, but knew he had an extensive file on her activities. Sometimes he kept files for no other reason than spite: the author Raymond Chandler once rudely brushed off a Hoover invitation for a drink, and the file on Chandler later ran to hundreds of pages. Chandler’s fictional bad guy characters may have needed extensive surveillance. He didn’t.

Eastwood’s film “J. Edgar” dramatized a moment when Hoover expresses his fears about his “personal” files after his death, who might get to them, and how that might make his life’s work look in retrospect. Helen Gandy assures him, no one will ever get to them. Don’t worry, Mr. Hoover.

LEGACY

In 2011, attorney Ken Ackerman’s piece in the Washington Post discussed “Five Myths” about J. Edgar Hoover. The word myth can mean a couple different things–sometimes false legend that people have come to believe. Sometimes just legend–it could be true, or not so much.

In 2011, attorney Ken Ackerman’s piece in the Washington Post discussed “Five Myths” about J. Edgar Hoover. The word myth can mean a couple different things–sometimes false legend that people have come to believe. Sometimes just legend–it could be true, or not so much.

The first “myth” engaged the issue of Hoover as a “gay cross-dresser.” He had a rather hidden sexuality if any at all, but does the issue matter, is it a Mystery of any importance beyond salacious gossip? If nothing else, it’s incredibly fascinating in the context of Mr. Rectitude, who expected incredibly conservative standards from his agents, who maintained files labeled “Sex Deviant” –speculations on the private behavior of consenting adults.

It strongly appears he was “deviant” himself in a number of ways, one of which may have been in his private, physical behavior.

More to the Mysteries of his secret surveillance operations:

Hoover had particularly good relationships with at least two presidents he served under: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. Of the others, Harry Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon all considered sacking him, but, files aside, they had good political reasons for keeping Hoover. Even in the 1960s, he had a strong public image as an honest, competent law enforcement technocrat. While his relationship with John and Robert Kennedy was often tense — yes, it was Hoover who, through wiretaps of Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, discovered President Kennedy’s affair with mob-connected socialite Judith Campbell Exner — Hoover also could have been covering up embarrassing secrets for Camelot.

Still, Hoover built his FBI files into an intimidating weapon, not just for fighting crime but also for bullying government officials and critics and destroying careers. The files covered a dizzying kaleidoscope — Supreme Court justices such as Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, movie stars Mary Pickford and Marilyn Monroe, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, physicist Albert Einstein, Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller III, among others — often replete with unconfirmed gossip about private sex lives and radical ties.

By 1960, the FBI had open, “subversive” files on some 432,000 Americans. Hoover deemed the most sensitive files as “personal and confidential” and kept them in his office, where his secretary, Helen Gandy, could watch them. Today, with few exceptions, Hoover’s FBI files are open for any American to see at the National Archives. They make fascinating reading and paint a stark portrait of power run amok.

Washington Post, Kenneth Ackerman, November 9, 2011

That almost half a million Americans were tracked as “subversive,” and this long after the tiny American Communist movement had essentially fizzled, should concern us greatly. Additionally, he kept vast files not on the “subversive” but on the powerful.

Were Presidents afraid to fire him?

Consider: you’ve had a lifetime career in politics, of necessity you’ve rubbed shoulders with the good, the bad, the ugly. Even if you haven’t done very much wrong in all those years you’re aware of how nasty some of it can be made to appear, exaggerated a bit, taken just a little out of context. If you have any common sense–and you haven’t risen far in politics if you don’t–you know what Hoover’s behavior is telling you.

He isn’t coming straight out with the words–“Mr. President, if you don’t treat me right, I can hack your career and your legacy into little pieces.” No, of course not, he doesn’t have to be impertinent with a President that way. The fact, increasingly well known, that he has extensive files on everybody, for a reason, speaks as loudly as those words.

Sometimes, a “myth” earns the checkmark of “true” because it passes a simple test, the basic common sense and logic test.

Critics often accused Hoover of cowardice, pointing, for instance, to the fact that he didn’t join the military in June 1917, when he finished law school and the country was entering World War I. Instead, he took a draft-exempt job at the Justice Department.

Hoover, by most signs, would have preferred to join his contemporaries going “over there” to fight the Germans. At Central High School in Northwest Washington, he joined the cadet corps and was its captain during his senior year. He relished the pomp and ceremony, marching in uniform and palling around with his fellow cadets.Later, at the Justice Department’s Radical Division, Hoover’s craving for action led him to participate in a raid in February 1920 against one of the most dangerous leftist groups of that period, the L’Era Nuova gang in Paterson, N.J. The agents carried guns and confiscated plenty of weapons and explosives. Hoover interrogated the group’s leader and extracted the only direct evidence about the 1919 anarchist bombings that prompted that year’s Red Scare.

Rather than fleeing the draft, the more likely reason that Hoover took the Justice Department job in 1917 was that his 61-year-old father, Dickerson Naylor Hoover, who suffered from mental illness, had been forced to leave his job as a government clerk without a pension, making young J. Edgar financially responsible for the family. If anything, Hoover’s guilt over staying behind probably added to his later zeal against subversives at home.

Washington Post, Kenneth Ackerman, November 9, 2011

Again, the question of Hoover’s cowardice or courage would seem to have little bearing on the real mysteries of his tenure. Nonetheless, the number of accounts of Hoover standing well back from a shootout, but then hopping forward for a photo-op once the bad guys are subdued, rises as a sobering suggestion of character.

As psychological or character mystery, it’s a study in itself.

There are two theories that Hoover had African American heritage. One has it that he was born to an African American mother and secretly adopted by the Hoover family, a theory based on discrepancies in certain birth and census records. However, genealogist George Ott investigated the claim, failed to substantiate it and said he believes it to be false.

More plausible are stories like that told by writer Millie McGhee in her 2000 book “Secrets Uncovered: J. Edgar Hoover — Passing for White?” McGhee, an African American, claims that, based on family stories and genealogical records, she and Hoover had a common ancestor, a great-grandfather, making him a distant cousin. Hoover’s father’s family had roots in Virginia and Mississippi in the antebellum South, where interracial liaisons were not uncommon. Some mixing in his family tree is a possibility but remains unproven.

Hoover’s attitudes on race reflected those in the old Washington, where he grew up, a largely segregated Southern city. As FBI director, he repeatedly refused to involve the bureau in investigating anti-black race riots or protecting black civil rights workers in the South, insisting that these were matters for local police, even after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Washington Post, Kenneth Ackerman, November 9, 2011

Now, that would have been something, had DNA testing existed in the 40’s or 50’s, had it been proven that Hoover had strong African heritage components in his make-up! The scandal can scarcely by imagined, it would have been the atom bomb of revelations.

Especially for Hoover, who would have been beyond mortified.

Before you dismiss it as silly gossip, watch the documentaries (available on YouTube) in which black families with the Hoover connection make the case for the “family secret.” We came away convinced, you might too.

Sources as staid and conservative as professional genealogy librarians and the like find a lot of irregularities in Hoover’s birth paperwork, they’re clearly suspicious. For the mystery investigator, there’s the allegation of chicanery, and much worse, in covering it all up.

We’ll leave that hint, and encourage you to dig in and explore.

Again, what does it matter? Obviously on these issues we’re not gay-bashing or race-bashing–if anything we’re “hypocrisy bashing.” Hoover was known to hate “homosexuals,” to strongly dislike blacks, to fiercely disapprove of thieves who stole from the public treasury. Yet he, himself, was all of those things (his misuse of public funds is now well documented and beyond dispute.)

Which leads into Ackerman’s “Myth Number 5,” that Hoover left a stain on the reputation of the FBI.

A “stain” is in the eye of the beholder.

So, what do you think?

****

We dedicate this space to new information, or any reasoned reader perspective, on the great story and great Mystery that was J. Edgar Hoover.