Intro

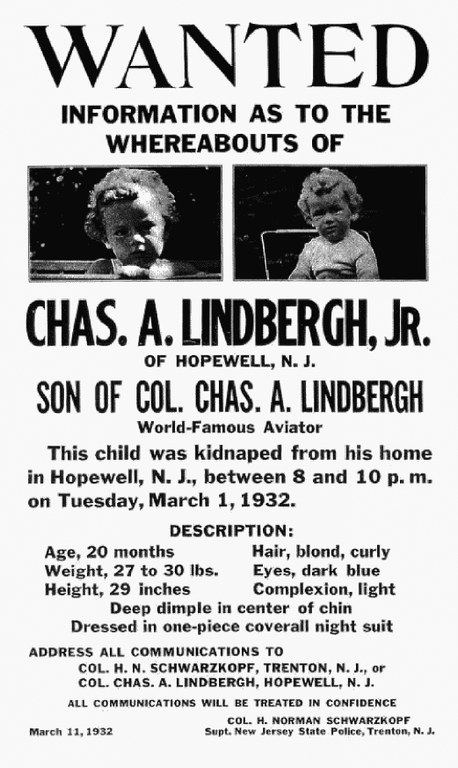

Famous aviator Charles Lindbergh was a man of rules and discipline. He told his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh, that their firstborn, Charlie, was to stick to a strict schedule. No one, not even his nurse, Betty Gow, must go in to check on the baby, even if he fussed, except at certain times. The 20-month-old Charlie, Lindbergh’s first child, was now more toddler than baby. A toddler that age laughs, is walking unsteadily, speaks small words such as Mama and Papa, and starts to experience strong separation anxiety.

Famous aviator Charles Lindbergh was a man of rules and discipline. He told his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh, that their firstborn, Charlie, was to stick to a strict schedule. No one, not even his nurse, Betty Gow, must go in to check on the baby, even if he fussed, except at certain times. The 20-month-old Charlie, Lindbergh’s first child, was now more toddler than baby. A toddler that age laughs, is walking unsteadily, speaks small words such as Mama and Papa, and starts to experience strong separation anxiety.

That steady routine was altered on Monday, February 29,1932. The baby had a slight cold, and Lindbergh instructed Anne not to travel and expose him to the weather.

At 7:30 P.M. on Tuesday, Anne and Betty Gow, the child’s nanny, put the infant to bed. Twenty minutes later, Betty Gow checked on the boy one last time. Lindbergh, who didn’t want his son coddled, had given strict orders that no one was permitted in the nursery again until 10:00 P.M., when Charles was taken to the bathroom.

At 10 p.m., the nurse asked if young Charlie was with his father, because he wasn’t in his crib. Lindbergh dashed up to check on Charlie. “Anne, they have stolen our baby,” Charles Lindbergh told his wife on the night of March 1, 1932, when he discovered Charlie was not in his crib. A ransom note left on the nursery windowsill read:

“Dear Sir, Have $50,000 ready … Have them in two packages. Four days we will inform you to redeem the money. We warn you for making anything public, or for notifying the police, child is in gut care.”

It couldn’t have been a bigger sensation in the news1 The Lindberghs and the authorities were inundated by lots of advice, and meaningless clues. Most of the world at least genuinely wanted to help. Even notorious gangster Al Capone offered his assistance, from prison.

A second ransom note was received by Colonel Lindbergh on March 6, 1932, (postmarked Brooklyn, New York, March 4), in which the ransom demand was increased to $70,000.

The third ransom note was received by Colonel Lindbergh’s attorney on March 8, informing that an intermediary chosen by the Lindberghs would not be accepted and requesting a note in a newspaper.

On the same date, Dr. John F. Condon, Bronx, New York City, a retired school principal, published in the “Bronx Home News” an offer to act as go-between and to pay an additional $1,000 ransom.

The following day the fourth ransom note was received by Dr. Condon, which indicated he would be acceptable as a go-between. Approved by Colonel Lindbergh, on March 10, 1932, Dr. Condon received $70,000 in cash as ransom, and immediately started negotiations for payment through newspaper columns, using the code name “Jafsie.”

After a call at about 8:30 p.m., on March 12, Dr. Condon received the fifth ransom note, delivered by Joseph Perrone, a taxicab driver, who said he received it from an unidentified stranger. The message was that another note would be found beneath a stone at a vacant stand, near an outlying subway station.

This note, the sixth, was found by Condon, and he followed instructions to meet a man, who called himself “John,” at Woodlawn Cemetery. They discussed payment of the ransom money. “John” agreed to furnish a token of the child’s identity. A baby’s sleeping suit and a seventh ransom note were received by Dr. Condon on March 16. The suit was delivered to Colonel Lindbergh and later identified as Charlie’s. During the next few days, Dr. Condon continued placing ads in the newspaper urging further contact and stating his willingness to pay the ransom.

On March 29, Betty Gow, the Lindbergh nurse, found the infant’s thumb guard, worn at the time of the kidnapping, near the entrance to the estate. Meanwhile notes kept coming–this case may have set a ransom note record! On the 30th the ninth ransom note was received by Condon, threatening to increase the demand to $100,000 and refusing a code for use in newspaper columns.

Shortly thereafter, on the same evening, by following the instructions contained in still another note, Condon again met whom he believed to be “John,” hoping to satisfy him with the original sum of $50,000. This amount was handed to the stranger in exchange for a receipt and still another document, which asserted that the kidnapped child could be found on a boat named “Nellie” near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts.

The ransom had been paid by the Lindbergh’s. And the child was not returned, but the hunt by local police, the Federal Bureau of Investigations, and even the public continued at a fever pitch.

On May 12, 1932, the body of the kidnapped baby was accidentally found, by William Allen, partly buried, about four and a half miles southeast of the Lindbergh home, 45 feet from the highway, near Mount Rose, New Jersey, in Mercer County. Allen,, an assistant on a truck driven by Orville Wilson found the decomposed body. Charlie’s head was crushed, seemingly clubbed, with a hole in the skull and some of the body members were missing.

YOUNG CHARLIE WAS MURDERED BUT WAS IT ABOUT MONEY?

There are two bodies of evidence that point in the direction of solving this mystery. One was resolved by execution. Another, an American icon, continues to be a suspect.

One interesting fact: the unusual extended stay by the Lindburghs’s is puzzling. Their house , Highfields, was under construction and the family only stayed on weekends. Early that week, Anne Lindbergh pronounced that Charlie had a cold and they would stay until he recovered. Very few people knew of this health issue controlling their schedule. Plans were day to day–and if the family hadn’t known until the last hour that they would be at Highfields that night, how did the kidnapper know?

One interesting fact: the unusual extended stay by the Lindburghs’s is puzzling. Their house , Highfields, was under construction and the family only stayed on weekends. Early that week, Anne Lindbergh pronounced that Charlie had a cold and they would stay until he recovered. Very few people knew of this health issue controlling their schedule. Plans were day to day–and if the family hadn’t known until the last hour that they would be at Highfields that night, how did the kidnapper know?

Rutgers professor emeritus Lloyd Gardner offers a theory that Charlie had health problems, based on physicians’ accounts and his daily need for a megadose of Vitamin D2 — and that his father, who had a well-known fascination with Social Darwinism and eugenics, might have wanted his less-than-perfect child out of the spotlight. Gardner theorized that Lindbergh might have arranged for a “kidnapping” to create public cover for placing Charlie in a medical institution, and that the child’s death was the result of a plan gone horribly wrong.

President Franklin Roosevelt earlier had changed Treasury policy to require the surrender of all gold and gold certificates held by individuals. This turned out to be a valuable aid in the case, inasmuch as $40,000 of the ransom money had been paid in gold certificates and, at the time of the Proclamation, huge numbers of these certificates were in circulation. On May 2, 1933, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York discovered 296 ten-dollar gold certificates, and one $20 gold certificate, all Lindbergh ransom notes. These bills were included among the currency received at the Federal Reserve Bank on May 1, 1933, apparently made in one deposit. Immediately upon the discovery of these bills, deposit tickets at the Federal Reserve Bank for May 1, 1933, were examined. One was found bearing the name and address of “J.J. Faulkner, 537 West 149th Street,” and had marked thereon “gold certificates, $10 and $20” in the amount of $2,980. Despite extensive investigation, this depositor was never located. Could it have been Lindbergh who was known to have gold certificates?

In most kidnapping cases family members are looked upon as possible suspects. Instead of becoming a suspect, American hero Charles A. Lindbergh was, in effect, allowed to run the investigation almost from the moment he reported his toddler son gone from their New Jersey home!

In her heavily researched book, “The Lindbergh Kidnapping Suspect Number 1: The Man Who Got Away,” author Lise Pearlman asks readers to consider the possibility that Lindbergh used his position to conceal the fact that he was personally – and intentionally – responsible for his son’s death. It’s the fifth book by Pearlman, a highly credentialed attorney who was the first presiding judge of the California State Bar Court, a position she held from 1989 to 1995.

She talked in a recent interview with The Topeka Capital-Journal about how Lindbergh – known as “the Lone Eagle” – became an international hero after he completed the first nonstop intercontinental flight from New York to Paris in 1927. Pearlman suggests that Lindbergh felt unhappy that his firstborn son was a “weakling” who had an abnormally large head and may have suffered prenatal damage when Anne Lindbergh inhaled toxic fumes as the couple made a record-setting cross-country flight in April 1930.

Lindbergh was a proponent of “eugenics,” the study of how to manage human reproduction to increase the occurrence of heritable characteristics regarded as desirable, and believed weak infants were meant to die, Pearlman writes. The book says Lindbergh showed little interest in the boy, repeatedly describing him as “it” and behaving toward him in a hostile manner several times during the last months of his life.

Further, supporting Lindbergh’s belief in eugenics, Perlman says he was openly a Nazi supporter. He sat in German dictator Adolph Hitler’s box at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin – and initially called for Americans to stay out of World War II and only stopped advocating that publicly after the December 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In highlighting his secretive nature, Pearlman writes that Lindbergh also fathered seven other children, unknown to his family back in the United States. Were these acts the urge to continue the Aryan race?

“Under an assumed name, from the late 1950s through the late 1960s, he secretly fathered seven illegitimate children by three mistresses in Germany,” Pearlman’s book says.

It says all three women had been put in touch with Lindbergh when they let it be known they would like to bear his children. Various authors have since contended Hauptmann was not responsible for the kidnapping and death of Lindbergh’s son. Gregory Ahlgren and Stephen Monier theorized in a book published in 1993 that Lindbergh was playing a prank when he dropped his son from a ladder, killing him, then hid the body.

Monier speculated there was another side to Lindbergh the hero. The man behind the public mask was “a social misfit,” a rigid loner with a penchant for cruel jokes. Once during his airmail piloting days, one of Lindbergh’s roommates returned from a night on the town and took a drink from a pitcher, only to discover that Lindbergh had replaced the ice water with kerosene. The pilot nearly died. Monier was taken aback. “The image I had was of a hero. But when I began reading, I was surprised to find that this was a cold, aloof guy, whom, frankly, I wouldn’t like very much.” Even if Hauptmann was innocent, was Lindbergh cold enough to let another man die in the electric chair? The authors think he was. “They didn’t call him the Lone Eagle for nothing,” Monier says.

What they needed was an eyewitness who could place Lindbergh in Hopewell early in the evening on March 1, 1932. They began to hunt for Ben Lupica. He was now a retired dentist but his memory was sharp.

In 1932 Lupica was a Princeton Academy high school student living near Hopewell. A few hours before the kidnapping, he was passed by a man on the road with a ladder in his car. The license plate matched Lindbergh’s state and the car had unusual grill work, as did Lindbergh’s. The man driving, said Lupica, was white. He was never called to testify about his circumstantial evidence.

Hauptmann was convicted of capital murder in the death of Lindbergh’s son. He died in the electric chair in April 1936 after refusing a last-minute offer to reduce his sentence to life in prison without parole in exchange for a confession.

A SCAPEGOAT WAS NEEDED, AND HAUPTMANN FIT THE BILL

Koehler disassembled the ladder and painstakingly identified the types of wood used and examined tool marks. He also looked at the pattern made by nail holes, for it appeared likely that some of the wood had been used before in indoor construction. Koehler made field trips to the Lindbergh estate and to factories to trace some of the wood.

In the end, a section of wood found in Hauptmann’s attic was said to be an exact match to the wood used to construct the ladder built to the height of the second-floor window at Lindbergh’s home, and used to abduct his son.

Examination of the ransom notes by handwriting experts resulted in a virtually unanimous opinion that all the notes were written by the same person and that the writer was of German nationality but had spent some time in America.

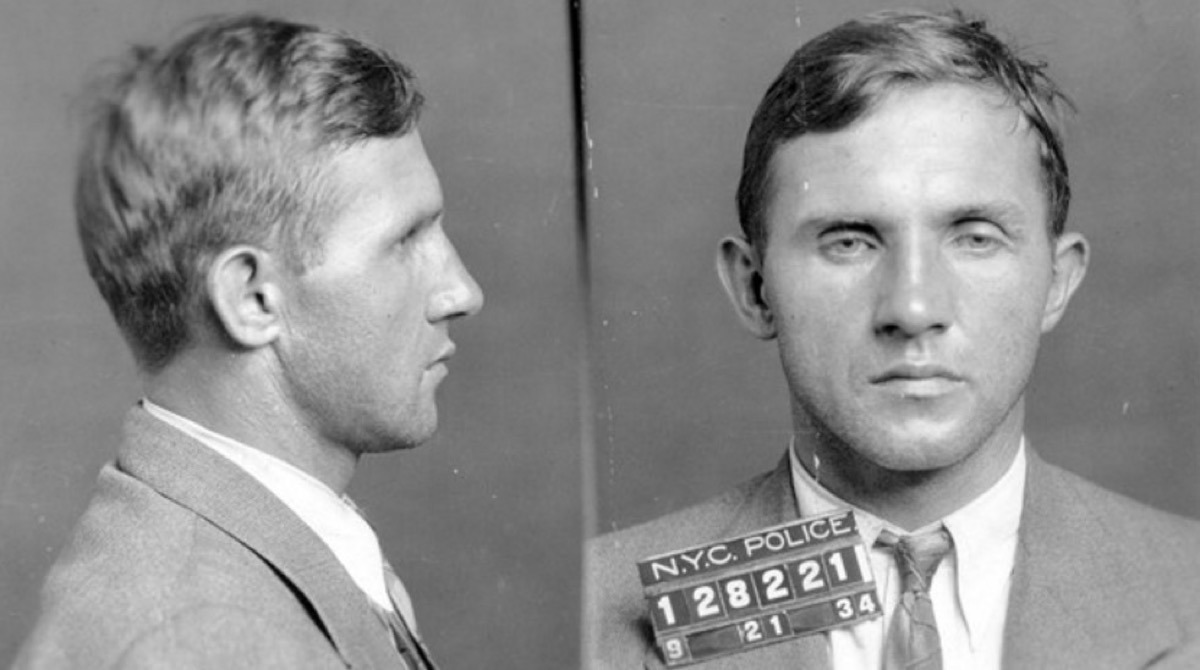

Authorities in September 1934 arrested German immigrant Bruno Richard Hauptmann, who had made a purchase using a gold certificate that was part of the ransom money. He was also a carpenter. Much of the ransom money was then found in Hauptmann’s garage. Hauptmann denied being involved, saying a friend had stashed packages of money there, without telling him what they were.

He said the gold certificates had been left with him by a friend, Isidor Fisch, who returned to Germany from the U.S. in December 1933 and died there of tuberculosis in March 1934. Hauptmann said he kept the money for himself because Fisch owed him.

Hauptmann seemingly had no connection to Lindbergh’s family but circumstantial evidence pointed to him. The sole link between Hauptmann and the site of the kidnapping was the match between the crude handmade ladder investigators found near the Lindbergh estate and the wood in Hauptmann’s attic, where police had found a floorboard sawn in half.

Shortly before his execution, Hauptmann gained an unlikely ally: New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman, who visited Hauptmann in prison, declared that he couldn’t possibly have acted alone, and granted him a 30-day reprieve. He ordered the case re-opened, as the prosecution’s key piece of evidence — holes in the ladder that matched nail holes in Hauptmann’s attic beams — weren’t visible in an early photo of the ladder. Nevertheless, the defense lost its appeal,

Still, Hauptmann was convicted of capital murder in the death of Lindbergh’s son. He died in the electric chair in April 1936 after refusing a last-minute offer to reduce his sentence to life in prison without parole in exchange for a confession.

Hauptmann claimed his innocence until he died. Was he guilty? A lot of evidence pointed his way. But there was no logic, none, under which he could have done it all alone. How would he have known about the remote estate, built a ladder just the right height, come to the window at just the right time?

By taking the scapegoat they had to the electric chair, authorities ensured no one else would ever be held accountable. That may not have been calculated, but it had the effect of closing a case which should have remained open until all facts, all co-conspirators were accounted for.

Charles and Anne Lindbergh had five other children between 1932 and 1945, all of whom grew to adulthood. Four remain alive as of this writing.

Charles Lindbergh died of lymphoma at age 72 in 1974, in Hawaii.

The tragedy inspired Congress to pass the Federal Kidnapping Act, also known as the Lindbergh Law, which made kidnapping across state lines a federal offense.