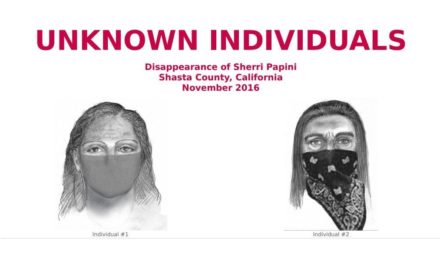

It’s been in the news as we write this, someone supposedly with high White House status writing a bombshell, anonymous letter published in the NY Times. Can the content clue us in to the author?

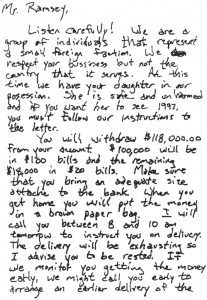

And it’s just the latest example: if we knew the author of many a special document, we’d know a lot more. In the ever-intriguing Ramsey murder case from 1996, perspectives on a likely murderer differ sharply, but all camps agree on one thing. The author of the ransom note participated in the crime, or knows who did.

Textual analysis is a thing now, emerging ever since Jim Fitzgerald of the FBI helped identify Ted Kaczynski as the Unabomber: among many other things, Kaczynski was prone to say “eat your cake and have it too” as opposed to the more common “have your cake and eat it too.”

Individual word use can make a stunning difference. Fitzgerald once broke a case where the perpetrator obliged by being the only guy on the planet to call to light bulbs “light bugs,” and foolishly wrote a note using the term. Authorities honed in on him like bees on honey.

So when an Slate article says individual words don’t mean too much, it seems like nonsense at first. But the author was really cautioning against over-emphasis on individual pieces of vocabulary at the expense of patterns– we all have a syntax, a cadence, a rhythm to our speech and writing which is, over the long run, somewhat different from anyone else’s. Our fingerprints, in written form.

And little things mean a lot. An author might not be quite be aware that he or she always writes out “it is” when most people use the contraction “it’s.” But textual analysis spots that, every time.

And keep in mind, it’s easy for a sly operator to note the favorite words of others, and use them as false bread crumbs. Whoever wrote the infamous White House insider note likely knew Mike Pence’s proclivity for the word “lodestar,” a very unusual favorite noun.

What better way to deflect attention in that direction, almost a little too obvious, no?

There’s the emerging science of textual analysis at play here, and the age old cat-and-mouse game of littering the landscape with false clues. Sherlock has to remain sharp, and skeptical, as he puffs his pipe and reads.