Amanda Knox

If you wanted a theme for a nightmare, a dream that would never let you sleep again, this would be it. You’re a young woman going to college in another country, with foreign chatter and differing folkways all around you. Your days in Italy start out as a time of fun, and learning, and handsome young men. These are exciting times, full of promise. Except that one night your housemate is murdered, brutally, her neck slit open. Police are everywhere for a time, asking questions of everyone.

That’s to be expected.

But when they start asking more questions of you than anyone, when they scream at you into the night, for hours, at the police station, to come clean, to confess, and finally indict you for the crime of murder, the good times are all over. The nightmare of the endless loop has begun. After several days your mother arrives from the United States, but it’s too late. Italian authorities claim that you’ve confessed already, sort of, and that you need to be detained, indefinitely.

Your name is Amanda Knox, and you may not have confessed to anything, but you are guilty of something. You’re guilty of being a free-spirited, eccentric young American woman in Italy, where the expectations of feminine behavior are more traditional. You’re guilty of not grieving enough when you learned of the death of your new friend, who shared your home.

You’re guilty of doing Yoga and even gymnastics at the police station, while Italian women looked on, aghast. Your whole way of dressing, of talking, of being, just don’t seem quite right here. So you attract attention, and suspicion. For you, it was a taste of Salem, Massachusetts in 1692, and the witchcraft scandals. If you act differently from everyone else, you must be guilty of something.

Knox was convicted and sentenced to 26 years in prison, then two years later a higher Italian court overturned the conviction—Amanda was released from prison and returned to Seattle to begin the rest of her life.. Then, in 2013 a still higher court re-tried the case, offering the specter of a re-conviction and an order to extradite Amanda back to Italian justice. On September 7, 2015, a final verdict cleared Knox and her former boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito of responsibility for the death of Meredith Kercher. The huge sigh of relief could be heard all the way from Seattle, where Amanda was engaged to be married.

Normal life could resume.

Now that the murder case recedes into history, you’ll hear less and less about Amanda Knox. But what happened in Perugia, Italy that fateful evening that so ignited emotions on both sides of the Atlantic? Why the loathing, and the informal conviction of Knox by the mainstream Italian press, and Italian people, years ago? Amanda’s case is a classic small town tale, of bias and posturing, and genuine crime, and corruption. What journey of understanding can she take us on?

THE PHENOMENON

The case of Amanda Knox offers international intrigue at its finest,” proclaims a brief video on the case available, where else, on YouTube (“Bizarre Things That Never Made Sense About the Amanda Knox Case”). In fact, YouTube offers so many videos on the Knox case, from two minutes to two hours, that you can watch them ad nauseum. We mean that more or less literally—there’s much to be nauseous about in this murder. The crime itself, brutal, bloody, perhaps not actually Satanic but so awful as to rate as truly beastly. You could be nauseous as well at the judicial rush to judgment. On only the evidence of how young, sometimes stoned college students behaved around a crime scene, a chief prosecutor quickly conjured a theory of the crime. He decided it was obviously the work of a depraved, sadistic Knox and boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito, and then jammed round pegs into square holes in his zeal to make a case.

If the prosecutor’s blind haste didn’t upset you, local and international media coverage would have. ‘If it bleeds, it leads’ runs the old saying, and that multiplies by ten or so when you add rape, beauty, and “international intrigue.” Just who was this American girl, mesmerized Italians asked themselves, as the case was thrust at them hour after hour on their television screens? She’s beautiful on the outside,…but those steely blue eyes are hiding a murderous spirit, or so says our prosecutor and he’s says it’s her that cut that other girl’s throat open…

She was hated. Had she been turned loose in Perugia’s streets, you almost wonder if a crowd would have burned her at the stake.

It seems that some players in the judicial system, and the public consuming daily news, had decided early on just who committed this brutal murder. Things like evidence, and a trial, would be merely a formality. According to accounts, Amanda’s treatment in police custody used the oldest if not the kindest of methods. If we yell at you about your guilt, hour after hour after hour while police take shifts but you have to sit and take it, we’ll finally wear you down, you’ll finally collapse and say anything. Amanda remembers that as the strangest nightmare of all.

Finally, there are the sharp, surprising turns in the Italian justice system–a conviction, an acquittal, followed by a conviction, followed by…an acquittal, from the equivalent of the Supreme Court, presumably the end of it. But if you were traveling on the prison roller-coaster, either Know or Sollecito, you’d be worn thin by the multi-year process. It was confusing, so many changes of course, back and forth.

For all of the drama that stretched on for years, it was never that subtle a case, never that much complexity from the standpoint of forensic science, or witness evidence, or anything else. But there was enough emotion and raw mass-media appeal to make up for all the substance that just didn’t exist.

“Finished!” Knox’s lawyer Carlo Dalla Vedova exulted after the decision was read out late Friday. “It couldn’t be better than this.”

The surprise decision definitively ends the 7½-year legal battle waged by Knox, 27, and co-defendant Raffaele Sollecito, 31, to clear their names in the gruesome 2007 murder and sexual assault of British student Meredith Kercher.

The supreme Court of Cassation panel deliberated for 10 hours before declaring that the two did not commit the crime, a stronger exoneration than merely finding insufficient evidence to convict. Instead, had the court-of-resort upheld the pair’s convictions, Knox would have faced 28 ½ years in an Italian prison, assuming she would have been extradited, while Sollecito had faced 25 years.

“Right now I’m still absorbing what all this means and what comes to mind is my gratitude for the life that’s been given to me,” Knox said late Friday, speaking to reporters outside her mother’s Seattle home.

The case attracted strong media attention due to the brutality of the murder and the quick allegations that the young American student and her new Italian lover had joined a third man in stabbing to death 21-year-old Kercher in a sex game gone awry.

Flip-flop guilty-then innocent-then guilty verdicts cast a shadow on the Italian justice system and polarized trial watchers on both sides of the Atlantic, largely along national lines.

Associated Press, September 8, 2015

The excerpt above was from the AP, written by an English-speaking journalist. The Italian press, and populace, has generally been happy at the long prison sentences, never been thrilled at the acquittals. Many there still think she’s as guilty as sin.

Why the national divide? For many reasons, perhaps, for one the same nationalism that has Italians cheering wildly for their soccer team to beat the U.S. in the World Cup, and vice-versa. A bona fide Italian prosecutor, and Italian courts had tried and convicted this devious (in Italian perception) foreign character, and no slick lawyering or American whining should get her off.

She’s a symbol, perhaps, as a privileged American girl, in a country that’s seen tourists from wealthier nations pass through with a sense of arrogance and privilege, for generations. They may not have been aware that Amanda worked her tail off, back in the States, for countless hours to earn the funds for her college year abroad. She was not born with a silver spoon in her mouth, but stereotypes are powerful.

And at the end of day, Amanda was the type of American girl of her era–zestful, free-spirited, uninhibited–that doesn’t always go over well in provincial Italy. The expectations of young women are different there, a more conservative decorum is expected. So when Amanda, dressed in the casual sweats she’d been wearing, was doing casual Yoga-type stretches and the like down at the police station, to relieve the tension, Italian sensibilities were offended. What kind of girl would act like that? At a time like this?

She struck every Italian eye as at least different. And as a Senior Editor at MindOverMystery loves to remind us, the error of equating “different” with “guilty” in some way has been one of civilization’s most consistent, and often tragic, mistakes.

At the end of the day, Italians were nauseated, too, tired of the very real phenomenon of Americans-acting-badly abroad, and how someone always makes excuses for them.

On the American side of the exchange, once at least it was clear how weak the case against Amanda was, we rallied, most of us, as to an American skater competing in the Olympics. We’re all for this girl, how can we help her? Retired FBI agents, and the like, began researching and assisting in the case, generally on their own dime.

We can only wonder where international relations would stand if the Italians had not exonerated her in their final process. If they had re-convicted her, they would have then demanded extradition of the young woman who had gone back to Seattle–after all, murderers are extradited between countries.

It’s a frightening hypothetical. Italy and the U.S. might not have actually gone to war, but at one level, it would have felt like it.

At the end of the day, we saw more twists and turns in this case than in the most convoluted mystery-movie plot. If you offered this as a film script, it would seem over the top.

Really, you can’t make this stuff up.

THE MURDER CASE, THE EVIDENCE

There are a host of places, from lengthy documentaries to full-bodied books, where every wrinkle of this case is discussed in great detail. We won’t recount all that here for two reasons:

1) You’d already be reading a 300-page book if you wanted to read that much.

2) Most of what you’d read is irrelevant, anyway, although the case still offers some subtlety, complexity.

The important facts, reviewed:

1) Amanda and Raffaele Sollicito, her boyfriend of a little more than a week, maintain they had spent the night at his place. She came back to shower at her own place the next morning and noticed traces of blood in the bathroom, that were alarming to her but not exceedingly so at first.

2) When the Italian police were alerted and finally broke through a locked door to discover Meredith Kercher murdered, Amanda and Raffaele stayed a distance away. Some police found that suspicious, especially in hindsight.

3) Important steps in general police forensics were missed, notably the body temperature of Kerchner was not taken when first discovered, making the highly significant time of death impossible to fix later.

4) Before long Amanda was questioned, without counsel or US Embassy representation or a neutral translator, at local police headquarters. Within days, the questioning intensified to multi-hour sessions of aggressive interrogation.

5) Authorities discovered a plethora of evidence that a petty criminal named Ruedy Guede, originally from the Ivory Coast, had been involved in the murder–blood, DNA (including inside Meredith’s body), such a striking trail of evidence that no defense counsel ever tried to exclude him from the murder scene. He fled Perugia long before anyone began looking for him.

6) Before Guede was identified and brought back, authorities began a full court press on Amanda. Her mother was on the way from the States, but didn’t move fast enough. Amanda was questioned, very roughly she alleges, for so many hours she finally “broke down.” She was berated to push past her “amnesia,” so she eventually imagined she might have been at that scene, and that her employer at a local restaurant, Patrick Lumumba, was there, too. He was quickly picked up by police and held until his clear alibi was established.

7) Amanda now had more Italian enemies all the time. Lumumba and his lawyers were angry, and his lawsuit against her played out simultaneously, further tainting her court case.

8) With Patrick Lumumba out of the picture, prosecutor Giuliano Mignini put Rudy Guede in the crime, substituting one black perpetrator for another, along with his theory of involvement by Knox and Sollicito.

9) Guede, as he faced trial, had a gradually shifting story. He originally said Amanda wasn’t around that night, then began shifting such that by the time of her trial, his story was consistent with Mignini’s narrative.

10) Knox (and Sollecito) were eventually tried for murder, on the basis of Guede’s evolving story, of Amanda’s “confession,” of various anomalies in their stories and behavior, and on elements of dubious forensic evidence.

11) Although the “innocentisti,” those who tended to believe an innocent Amanda was being railroaded, brushed aside elements of circumstantial evidence as throw-away trivia, there was a lot to think about. Why did Amanda call her mother at 4am Seattle time before the body was even discovered (a point on which she was presssed by a judge in the case), why did she and Raffeale switch off their cells early the night in question, why did they say they downloaded and watched a movie when IT techs later said different? Why the divergent stories overall from the two who held each other’s alibis, why the mop bucket in plain sight, why a warm washing machine, why so many inconsistencies, allegedly, in statements and events? In addition to trace evidence of their DNA at the scene, however disputed.

Italian correspondent Barbie Latza Nadeau of The Daily Beast, and other “colpevolisti,” always leaned toward some culpability for the pair. They found it hard to imagine that so many sore thumbs of evidence, eight or ten or twelve depending on what you count, could all be coincidental and easily explained away. While not pretending to know precisely what happend that night, they doubted that Amanda and Raffaele were the totally innocent deer in Italian justice headlights as portrayed by the U.S. American press.

12) It’s said that Amanda and her family were optimistic in her acquittal, with no logic and thin evidence, by their lights, supporting her involvement. But most courtroom observers, noting not only evidence and confession but also how out of step with Italian expectations Amanda looked, playing in to aggressive prosecutors, expected conviction.

When convicted, she was given a twenty-six year sentence.

13) To expand on the perception issue with Knox, it became Italian gossip during her trial that she was sexually active, and not just with some future husband. American journalist Judy Bachrach learned the important of this in seminars she taught in Italy, when a young man wondered how she could possibly consider Amanda an “innocent” person.

His assumptions of guilt seemed driven by sexual thinking. “In Italy it is not O.K. for a girl to sleep with more than one man. A man can sleep with more than one girl, but the reverse just isn’t acceptable!” he exclaimed.

14) Besides public perception, the prosecution’s case involved supposed traces of DNA on minor items, where the science wasn’t clear, and on Amanda’s confession statement (long recanted), and various circumstantial observations, although they added up in sheer number.

There was a person or two who placed Knox, or Sollecito around the scene that night, except that they couldn’t be absolutely sure it was that night, or that it was them. There was nothing concrete from the murder bedroom, and the DNA from these suspects in the chaotic scene was disputed.

Nevertheless, the court didn’t really hesitate, it was Guilty of Murder.

15) Mignini had successfully made his case. Amanda spent the next four years in prison, until released in her first “acquittal” and allowed to fly back to the States.

MISSING: MOTIVE, EVIDENCE, AND LOGIC

In the previous section, we presented in thumbnail sketch the basis of Amanda Knox’s conviction, the evidence as presented by Italian prosecutors.

Numerous legal standards and customs vary culture to culture, for example Italy does not have, per se, the standard of “beyond reasonable” doubt.

Nonetheless, it’s far from certain that Knox would have been convicted of murder, a highly violent, crazed murder no less, without her “confession,” of sorts, to the crime.

We were among those who used to think: confession. That’s always pretty strong. Why would an innocent person confess, short of torture with hot irons, to anything they didn’t do? Couldn’t you just keep protesting, and keep protesting, and keep protesting your total innocence, until the authorities give up on the attempt?

We used to think that, but we’ve been educated. For one thing, anyone who wonders about the psychology of induced confessions should, really must watch the Netflix series “The Confession Tapes.” You’ll find it more than illuminating.

That’s not to say that everyone who confesses to a crime under duress rates as innocent. It is to say that the techniques are extreme, and quite powerful, and leave you not knowing what to believe.

As one Senior Editor at MOMystery quipped, “if they used those methods on me, I’d end up confessing to the Lindbergh kidnapping.”

We don’t have tapes of Knox’s supposed remarks, but apparently, after many long intimidating hours, she finally agreed to “imagine” or “envision” the crime scene, which is when she (erroneously) put Patrick Lumumba there, and when she seemed to put herself there, hearing horrific “screams.”

What are we to make of all that? Very hard to say, but we could give the “confession” more credibility if it wasn’t extracted by extreme methods. Or if it was consistent with any real logic or substantive evidence. It isn’t.

This section emphasizes what the prosecution didn’t have, not what they did. Any roommate might have the proximity, the “opportunity” to commit a murder, but motive?

There’s not even a glimmer of motive. No hate had developed between roommates at the house. Nothing in Amanda’s emotional make-up, or background, to suggest that brutal, vicious murder, that violent acts of any kind, were in her make-up.

Violent murder out of the blue, with no background or reason or supporting psychology, is extremely rare, almost non-existent. You could believe it, you could prosecute it, only if you found clear, absolutely overwhelming forensic evidence of guilt that simply couldn’t be explained away.

In this case, there was none. The murder scene was, simply put, a bloody mess, with blood tracked everywhere. How could Amanda and her beau have been in the middle of that and not left evidence of themselves, or dragged a trace unknowingly back to his apartment? You can’t see DNA. You often can’t even spot traces of dried blood with the naked eye, which is why forensic experts use the tools of their trade, such as Luminol and other agents, to literally bring latent evidence (such as areas cleaned of blood) to light.

So, if we theorized that Amanda and her accomplice, coming back down to earth after an episode of true lunacy, contrived to erase all evidence, we would be theorizing the nearly impossible.

How could anyone, even a forensics expert, manage to erase all traces, many invisible, of their presence at a crime scene, while leaving all the blood and footprints and contamination that led straight to Rudy Guede? Even if they had a full twenty-four hours to work on the project, which they did not, they’d surely overlook something incriminating at the crime scene.

Outside of Italy, few with knowledge of modern forensics thinks that Amanda and Raffaele could have managed that, erased the traces of their presence there.

Simply put, they weren’t in the room when Meredith was killed.

How could they have been? Why would they have been?

Note–A journalist who once weighed in on the case, skeptical of Knox and Sollecito, had asserted the following:

“The simple facts are also that innocent people don’t change their story–not once, not ever. Innocent people have air-tight alibis. Innocent people become very emotional and do whatever they can to help the investigation; they do not try to delay the police, strain credulity with their elaborate explanations, or behave selfishly. Innocent people show huge regard for the person who died, and for the family of the deceased too.”

Our comment: Some of that is a little off, and some just downright silly.

Examples:

“Innocent people have air-tight alibis.” Of course not in many cases, someone can be home in bed, but unable to prove it.

“Innocent people become very emotional and do whatever they can to help the investigation.” Again, the writer is not knowledgeable. Not aware of how differently people act under stress, for one thing (and finding a roommate murdered and police chattering excitedly in a foreign language would stress anyone out).

We offer this to point out: even a journalist’s supposedly serious work can be devoid of logic, and thus not worth your time.

CROSSING CULTURES

“Now that the results of that botched investigation have been definitively voided, the question is: How much? How much does Italy owe two young people imprisoned for a murder in which there was no credible motive, no credible evidence, and no credible witnesses?”

Vanity Fair, Judy Bachrach, April 3, 2015

Judy Bachrach (who writes for Vanity Fair), familiar enough with Italian culture to teach journalism there in Rome, asks this very “American” question.

It plays differently elsewhere. Bachrach concedes that outside of the U.S. she never got too much traction with her strong assertion of Amanda’s victimization. In Britain (the country that sent Kercher to Perugia), they chalk it up as rooting for one’s own. And in Italy, forget it, most never saw Amanda as a victim, to put it mildly.

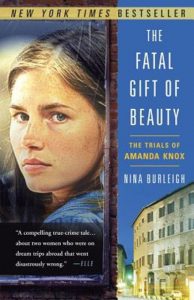

The best book on the case, by far, is Nina Burleigh’s “The Fatal Gift of Beauty,” a gem of modern long-form journalism.

The best book on the case, by far, is Nina Burleigh’s “The Fatal Gift of Beauty,” a gem of modern long-form journalism.

She tackles an obvious question, one that so many others ignore. Why? Why was Giuliano Mignini so convinced, so determined to pin the murder of Meredith Kercher on Knox and her boyfriend?

Italy shares much basic cultural framing with us, a primarily Catholic country in the modern, industrial world dominated by the Judeo-Christian tradition, and by the secular religion of business, progress, and luxury. Jumping the U.S.-Italian cultural gap is nothing like, say, jumping the gap of a Western country to Saudi Arabia, with starkly different religious norms, and an unreadable (to Westerners) language.

Italian Americans immigrated here, at least we believe, without confronting insurmountable cultural ramparts.

However, superficial similarities can disguise powerful differences. According to Burleigh, it’s more common in Italy for utterly devout Catholics (like Mignini) to believe in a rather literal struggle between God’s forces and the Devil’s, and to believe in structures of Satanic belief, and Satanic action. Thus, when patterns of sex followed by (almost ritually savage) murder, with a side show involving a black cat (apparently sighted in the area), paraphernalia left over from Halloween (not celebrated by Italians), and a couple of other odd items-when a few of the symbols that Mignini thought of as Satanic props appeared to be present, his imagination hit overdrive.

After that, there was no convincing the man that Knox was only an all-American girl, the independent and free-spirited version. We know she was infinitely less likely to be involved in witchcraft than in being a guy-connoisseur, an athlete, a lover of good movies leavened by cheap pot. We recognize her as an American thoroughbred of Seattle provenance, even if he can’t.

After that, there was no convincing the man that Knox was only an all-American girl, the independent and free-spirited version. We know she was infinitely less likely to be involved in witchcraft than in being a guy-connoisseur, an athlete, a lover of good movies leavened by cheap pot. We recognize her as an American thoroughbred of Seattle provenance, even if he can’t.

Amanda worked while in college to finance the year abroad. In Italy, she juggled college in a foreign language (exciting but quite difficult), a job at a restaurant, and men and friends and recreation. When in heaven’s name would she have time for elaborate Satanic activities, even if she had a history of them, which she didn’t? But what makes no sense to us made sense to Mignini.

You must remember, he didn’t grow up in Seattle, she did.

Everything is seen through a cultural lens, as if we put on the spectacles of our own experience, every day, to peer at the world through. “Thinking outside the box” is celebrated in recent years, but the box it’s hardest to spring out of is our own culture, and its preconceptions.

Often we even forget to ask, how’s all of this looking and feeling to others? And as America obsesses over Amanda’s unique predicament, how often have we returned our thoughts to Meredith Kercher and her British family? Her loss is permanent, irretrievable.

And how much thought, really, do we give to the battered life of one Raffaele Sollicito, the young, unassuming Italian guy who exchanged smiles across a room with Amanda, and was soon in a love affair?

You might almost say he was “collateral damage,” that ugly phrase, in a murder investigation that focused on Amanda, but took him along for the ride. If Amanda was into group Satanism, as seemed obvious to our prosecutor, wouldn’t her young lover be part of that Devil’s bargain?

Shy, slightly nerdy, a computer geek, inexperienced with women, Sollicito’s also a type we recognize, even across the Atlantic. Except for a stupid pose with meat cleaver in hand for an on-line humorous picture, there’s about as much reason to suspect Raffaele of Satanic murder as there was to suspect Mother Teresa of running a Mafia cell on the side.

Shy, slightly nerdy, a computer geek, inexperienced with women, Sollicito’s also a type we recognize, even across the Atlantic. Except for a stupid pose with meat cleaver in hand for an on-line humorous picture, there’s about as much reason to suspect Raffaele of Satanic murder as there was to suspect Mother Teresa of running a Mafia cell on the side.

We might assume that Mignini, given his generation and devout background, didn’t quite “get” how social media postings and posings could look so nuts at times, just as juvenile jokes. An internet species of sound and fury, really signifying absolutely nothing. They even unearthed a photo of Amanda posing at some museum with a huge machine gun, a stupid grin on her face. We get it, we see postings on Facebook everyday that make responsible adults look like adolescents again, and dorky ones at that.

But did Mignini even begin to get it? He, like all of us, is the prisoner of his background, and his view of the world.

THE PAST AND THE FUTURE

Most people think of the Amanda Knox story as the trial that followed the murder of Meredith Kercher, and the final legal resolution. A “whodunit?” murder case.

We include the case here among our Social and Psychological Mysteries because it’s so much more than that–a study of several key personalities, set amidst the justice process–usually as much psychology as justice, in all times and places–and mixed with the rich social psychology and national psychologies surrounding it all.

Our Psychological Sherlock has a lot to chew on, to try to understand the whole picture. We’ve tried to hit the high points here, but hope, over time, to add many an interesting quote or story to the whole, fascinating legend.

Our files on these mysteries are a work in progress, always open to new information, new stories within the story.

One chapter we’ll add one day revolves around “The Monster of Perugia,” the name some of the U.S. press have (perhaps unfairly) given to one Giuliano Mignini, the prosecutor who made the lives of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollicto such a living hell, for so many years.

We don’t admire him for that. But if you dig deep, it’s possible you’ll find him a victim as well–just not in the Knox case. From what even pro-Amanda journalists write, Mignini has tried more than once to solve crimes that involve corruption at high levels of Italian political power. He’s been hammered back down, and in the process accused of being the problem himself–that’s how it often goes when you try to fight powerful forces.

Is he a hopeless grandstander? A paranoid who sees a Satanic plot behind every bush?

Mignini, with his bizarre-seeming theory of the Kercher murder and stubborn handling of the case, deserves little merit there. Not everyone agrees he was on the right track in his other celebrated cases, but the last chapter of all that hasn’t been written.

Wouldn’t it be ironic, if and when the full stories are ever unearthed, Mignini turns out to be an unsung hero in those other episodes, fighting for what’s decent against rancid power brokers in his native land?

Among the mysteries of human psychology and spirit, we’re left with the question, What Now for Amanda Knox?

There are so many questions of the psyche.

A young adulthood, yanked loose from its usual moorings, so abruptly.

In prison, with no end in sight. A twenty-six year sentence might as well be life, when you’re not even twenty-six years old.

Despair doesn’t begin to cover it for someone languishing in prison, thousands of miles away from home. Whether you believe them guilty of a crime or not, there they are, in Dante’s inferno, with no way out.

Despair doesn’t begin to cover it for someone languishing in prison, thousands of miles away from home. Whether you believe them guilty of a crime or not, there they are, in Dante’s inferno, with no way out.

Knox reported almost unimaginable guilt for the disruption to her family’s life, tranquility, finances. They sacrificed enormously to be with her, some 7,000 miles from Seattle.

She says she was looking for a way, when she thought she’d sit there twenty-six years, to tell her family to just, simply–let her go. To move on without her, to not let their lives be swallowed up by hers.

She says at times she considered suicide.

And the roller-coaster ride of guilty, acquittal, guilty, innocent… can you even imagine. Without a shudder, deep down?

And now, that the legal problems have been conquered…

How do you ever have a normal life, after being the spectacle of two continents?

Everywhere you go, every time you’re seen outside your home–do you have to wonder? What are they thinking? They keep staring. I’m not a person to them, not a normal one anyway, I’m that girl.

Below, a link to one of the many YouTube videos of approachable length…