Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

“This is a most unusual case. It was so from the beginning. As it goes on, it gets more and more unusual.”

Judge W. Preston Battle, Shelton County, Tennessee, December 18, 1968

Unless the case was completely cooked from the start, lots of evidence points to James Earl Ray as involved in the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King. Even Ray never claimed that he had nothing to do with it, not until later when he had a lot of time to concoct alternative scenarios.

But was there more to the story than Ray’s confession, life sentence, and death in prison? Why would a career petty criminal, with no known history of racial violence, become involved in a political assassination? How did this small-time character make it out of the country, all the way to London, before capture, unless he had professional help?

And can the FBI be trusted to give an honest account of the whole affair, when only a couple of years before they had tried to coax King into suicide?

Imagine that Sherlock Holmes was called to the scene just after April 4, 1968, and asked to solve the crime of the Martin Luther King assassination. What would he explore, and what would he conclude?

As we know, Holmes deduced the truth of many a case by “eliminating the impossible,” such that the final remaining possibility, however strange to the sensibilities, emerged as the ultimate truth. But so many mysteries in real life, including the King assassination, live at the intersection of numerous possibilities, none of them impossible, but none of them provable. The modern mystery detective must keep digging and keep thinking, aware that the truth may remain forever elusive.

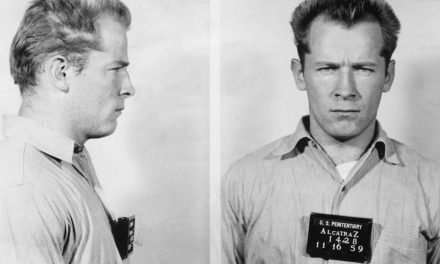

The sole accused and convicted assassin, James Earl Ray, does appear to have been at the scene of the crime, at least involved in the hit. An escaped convict, working hard to maintain a low profile in order to maintain his freedom, quite deliberately checked into a rooming house near King’s hotel, making sure to get a room with a gunman’s view out the window. Was he ready to commit the highest profile crime since JFK’s assassination? A man who never did anything “if it wasn’t for money,” according to his brother, supposedly shot MLK on general racial principles. He accepted responsibility, pled guilty to avoid the death penalty, and at first said he acted alone. Yet once convicted and imprisoned, his story changed, spurred on by professional writers like William Bradford Huie who offered cash for engaging narrative.

A shady “Raoul” had drawn him in to a gun-running scheme, had him in Memphis and close to King on false pretenses, he finally asserted. He didn’t know who Raoul represented, but they were well-connected people, that much was obvious…. And far beyond any jail-house allegations by Ray himself arise the hundred and one anomalies of the case.

Why were so many teams of investigators–from a Memphis Police intelligence squad to representatives of army intelligence to a clear FBI presence, even an FBI informer with King as he died–why were all these spooks tracking King so closely yet not alert enough to see the assassination brewing? How did Ray flee the area even as his name and description were put out on police airwaves? Why and how, when he arrived in Toronto, did Ray operate with more than one alias taken from a real Canadian who matched him in general physical description? Were the envelopes brought by hand to his rooming houses cash to finance the next leg of his journey, his travels through Europe, where he was arrested? The testimony about his flight from the crime, captured by Canadian and American police and journalists and later by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, goes on and on, always suggesting another possible avenue to probe.

Many theorists have leapt to conclusions they can’t prove–such as a hit by the CIA to silence a dangerous populist who criticized the basic justice of our system, as well as the war in Southeast Asia. That allegation may be extreme, but for many the notion that Ray dreamt up, and managed, the assassination and escape all by himself also stands as extreme. It fails to pass the common-sense test.

So, Sherlock is left to sift through a thousand elements of (mostly circumstantial) evidence and deduce the likeliest scenario. If you wear Sherlock’s hat and review this case, whom if anyone do you think colluded with James Earl Ray? Or was he one more deranged lone gunman, eager to really be somebody for the only time in his life?

We open the file and the challenge: just what happened with the assassination of Martin Luther King?

THE STAGE AND SETTING

If you didn’t live through the 1960’s, it’s not easy to convey the ferment, the chemistry of the change from an old America to a new one. As the eloquent voice for the nation’s most visible, downtrodden minority, Martin Luther King stood several feet taller than his 5 foot, 7 inch stature.

From the Washington Post on the 50th Anniversary of his most famous speech:

But of course, it was not King’s only great speech–and perhaps not even his most courageous. As historian Peter Ling writes in a history of MLK’s leadership style on BBC.com: “While it is customary to judge leaders by their successes, it may be argued that King showed his most heroic leadership after 1965, when he championed a U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, and the tackling of poverty and deprivation in black ghettos, with little success.” It took courage to fight segregation in the South, Ling writes, but “it took equal courage to challenge the President on foreign policy and to demand a massive redistribution of wealth and power to the underprivileged.”

Of course, many people haven’t heard King’s other speeches, not only because of their more radical nature, but because King’s speeches and papers are owned by his descendants and not all are readily available to be heard in their entirety. In them, however, he is just as much an inspiring leader, championing not only racial justice but an end to war and an end to poverty. He uses them to explain the larger context of how he sees these three issues as inextricably joined.”

Washington Post, 50th Anniversary

A take on the importance of the speech, but also King in context in America in the 1960’s, from across the pond:

“While it is impossible not to sympathise with the sentiments expressed in the stirring finale, as King imagines a world of interracial harmony where people ‘will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,’ too much emphasis on the ‘Dream’ can obscure other important aspects of King’s magnificent oration.

“The speech bristles with barely concealed frustration at the slow pace of federal action to support black civil and voting rights.

“Brilliantly blending practical politics with his inspiring social vision, King reminds white Americans of the continuing abuse of black rights (African Americans generally did not need reminding), condemns the gap between America’s democratic ideals and the realities of its racial practices (hence the speech starts with a nod to Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”, and frames black demands within the context of America’s core civic values), and hints at the dire consequences of failing to address these issues immediately (the speech is haunted by the spectre of more militant black protest if nonviolent demands for basic citizenship rights are not met).

“I think it is also highly significant that King spoke at a march ‘For Jobs and Freedom’. ‘We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one,’ he warned, foreshadowing a struggle for equality of economic opportunity and against economic exploitation that, along with his anti-war activism, occupied King’s final years.

“Those topics remain relevant to all progressive movements and help to explain the enduring appeal of King and his finest speech.”

Brian Ward, historyextra.com, August, 2013

Brian Ward is a professor of American Studies at Northumbria University, Excerpted from historyextra.com, August, 2013.

His impact, real and symbolic, as the face of the emerging civil rights movement of the times cannot be overestimated.

“When I think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the words ‘Ambassador For Peace’ come to mind because it was through peace that he accomplished so much. He showed people that love, not violence, is the best weapon against haters.” – Keke Palmer

“Dr. Martin Luther King is not a Black hero. He is an American hero…” —Morgan Freeman

“I think he’s inspired the whole country and the world. The themes and the ideas of his movement have inspired many other movements subsequently to achieve revolutionary things through non-violence. And I think even looking at President Barack’s rise, it’s part of that fulfillment of what Dr. King dreamed about and worked for.” —John Legend

mlksociology.weebly.com

He was perhaps destined for greatness. A brief background sketch from Heritage.org

He was born Michael King, Jr., on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, the first son of the Rev. Michael Luther King and Alberta Williams. (The name change to Martin occurred during King’s early boyhood, following that of his father. The elder King’s name evolved over a period of years from Michael to Michael Luther to Martin Luther. The finalized form emerged in the mid-1930s, likely inspired by a visit to Germany.[6])

Young M.L. was the son and grandson of Baptist ministers. His maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams (whose own father, though enslaved, seems to have done some preaching in a Baptist church in Greene County, Georgia), rose to prominence as pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, helped organize various regional and national Baptist associations, was active in the Georgia Equal Rights League (whose leadership included the outspoken minister Henry McNeal Turner along with W.E.B. Du Bois), and served as president of the newly organized Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Upon Williams’s death in 1931, M.L. King, Sr. (“Daddy” King), assumed leadership of Ebenezer Baptist, in time surpassing his father-in-law as a leader in Atlanta’s black Baptist community and an anti-discrimination activist.[7]

Due to the influence of his father and to experiences of his own, King, Jr., came early on to detest the regime of racial segregation that ruled the South throughout his youth. In an account of his religious development written as a theology student, he recalled an incident in which, as a six-year-old, he lost a white playmate, a close friend for three years, when the latter’s father for racial reasons forbade any further association between them. “I never will forget,” King wrote in 1950, “what a great shock this was to me.”[8]

In his formal schooling during his boyhood, he seems generally to have displayed middling ability, but oratory was, unsurprisingly, a strong suit. As a junior in high school, he won his school’s public speaking contest, thus qualifying for a statewide competition for black students. His subject was “The Negro and the Constitution,” on which he sounded some principal themes of his later activism. “The spirit of Lincoln still lives,” he stated in closing. “America experiences a new birth of freedom in her sons and daughters…. My heart throbs anew in the hope that inspired by the example of Lincoln, imbued with the spirit of Christ, they will cast down the last barrier to perfect freedom.”[9] On the bus ride returning to Atlanta, young King and his teacher were cursed by the white driver for a delay in surrendering their seats to newly boarding white passengers; they were forced to stand for the duration of the trip. The adult King recalled, “It was the angriest I have ever been in my life.”[10]

King matriculated in 1944 at Atlanta’s Morehouse College, an institution rising under the leadership of Benjamin Mays, a scholar and civil rights activist whom King would salute as “one of the great influences in my life.”[11] An undergraduate sociology major, King decided during his senior year to enter the ministry. He was ordained a minister shortly after turning 19 and then, in fall 1948, began graduate study at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, an integrated institution where he would eventually be elected student body president and honored as class valedictorian. At Crozer, he became acquainted with the work of Walter Rauschenbusch, whose social-gospel tract Christianity and the Social Crisis he ranked among the handful of books that influenced him the most.[12]

From Crozer, King went on to pursue a doctorate in systematic theology at Boston University.[13] In Boston, even as he considered a career in teaching and scholarship, his guest sermons at local churches developed his reputation as an unusually skilled preacher. As his studies neared completion, notices came his way of prominent southern churches potentially interested in his services. His wife, Coretta (they married in 1953), was uneasy about returning south, but despite her misgivings, King accepted a position as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, in spring 1954.

At Dexter, the young pastor’s reputation grew quickly, and he took up the cause of equal rights almost immediately. The event that launched his career came in December 1955, when Rosa Parks, secretary of the NAACP’s Montgomery branch, was arrested for violating local and state statutes by refusing to surrender her bus seat to a white man. A group of Dexter congregants immediately initiated a boycott of Montgomery’s buses, and clergymen and other community leaders convened to formalize the planning. They founded the Montgomery Improvement Association and elected the 26-year-old King its leader.”

Peter C. Myers, for Heritage.org, March 28, 2014

It would be fair to say that the young King was the right man in the right place at the right time, to assume the mental of a generation’s civil rights struggle. And his conscience drove him beyond the issues of civil rights, for example to fervent opposition to the War in Vietnam. His lasting impact perhaps owes much to his fight against the status quo using the language of the founding fathers. His respect for the nation’s founding principles was vast and abiding.

Again, Myers writing for Heritage:

Peter C. Myers, for Heritage.org, March 28, 2014

MEMPHIS

Then came that day in Memphis, part of the horrific near-end to a decade of American history roiled by unusual violence, upheaval, hope, and despair.

Just after 6 p.m. the following day, King was standing on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel, where he and associates were staying, when a sniper’s bullet struck him in the neck. He was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead about an hour later, at the age of 39.

From History.com, 2010

Time Magazine dusted off some of its memorable Letters to the Editor from the time of King’s assassination for the 50th anniversary..a sample:

“Sir: Martin Luther King was murdered because he was our uncomfortable conscience. I am filled with shame and loathing for my race. My heart grieves for his family and friends who must abruptly substitute memories for his warm reality. My mind cries out to know how I, one single me, insulated in my white suburb, can redress the ancient wrongs.”

The clergy and other persons of conscience weighed in:

From Rev. Lewis P. Bohler Jr. of Los Angeles:

“Sir: As a Negro, I, too, must bear my share of the shame and horror of Dr. King’s untimely death. Whether I burn or kill (by God’s grace, I hope to do neither), I am associated with those who do. And we dare to point indiscriminate accusing fingers at whites. The answer to whether Dr. King labored in vain will not be determined alone by the success or failure of civil rights legislation or by improvement of housing and economic opportunities for minorities, but also by the degree to which all of us, blacks and whites, are committed to the pursuit and practice of nonviolence and love. Any commitment short of total is a farce.”

From James Thompson, a pastor in West Branch, Iowa:

“Sir: Why must we always kill our prophets before we will listen to them?”

The dramatic event even charged the hearts and thinking of some who had shown little interest in the Civil Rights movement:

From Mrs. John Vadnais of St. Paul:

“Sir: Most of the time I was indifferent to the Rev. Martin Luther King‘s activities. Occasionally I scoffed at his publicity, although I was unconsciously reassured that someone was doing something for humanity. But I cried at his murder. Possibly King’s beautiful dream will ultimately result in his being remembered as a man, not a black man. The first step was taken as a thoughtful America united in mourning for a martyred leader. At any rate, our flag waved in a fellow American’s memory.”

And a view from abroad:

From P. Sudhir of Madras, India:

“Sir: Twice within five years, we had to hear from the land that all others strive to emulate, the harsh, frightening crack of an assassin’s rifle. The shots that were echoing around the world after the death of John F. Kennedy, shaking the belief that the U.S.A. is the last place where the courage of an individual to fight against man’s inhumanity to man would be met with the cruel bullet of an assassin, had hardly died away. And now Dr. King is dead, crucified on the cross hairs of a madman’s telescopic sights. Yes, that is the excuse we give ourselves. It is the work of a demented individual. Perhaps if we repeat it often enough, we might even come to believe it.”

But then began the acid questions. Just who killed the prophet, and through what motivation and circumstances?

On June 8, authorities apprehended the suspect in King’s murder, a small-time criminal named James Earl Ray, at London’s Heathrow Airport. Witnesses had seen him running from a boarding house near the Lorraine Motel carrying a bundle; prosecutors said he fired the fatal bullet from a bathroom in that building. Authorities found Ray’s fingerprints on the rifle used to kill King, a scope and a pair of binoculars. On March 10, 1969, Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. No testimony was heard in his trial. Shortly afterwards, however, Ray recanted his confession, claiming he was the victim of a conspiracy. Ray later found sympathy in an unlikely place: Members of King’s family, including his son Dexter, who publicly met with Ray in 1977 and began arguing for a reopening of his case. Though the U.S. government conducted several investigations into the trial–each time confirming Ray’s guilt as the sole assassin–controversy still surrounds the assassination. At the time of Ray’s death in 1998, King’s widow Coretta Scott King (who in the weeks after her husband’s death had courageously continued the campaign to aid the striking Memphis sanitation workers and carried on his mission of social change through non-violent means) publicly lamented that “America will never have the benefit of Mr. Ray’s trial, which would have produced new revelations about the assassination…as well as establish the facts concerning Mr. Ray’s innocence.”

Time retrospective, April 4, 2015

From the historical information website launched by a noted researcher, the late Mary Ferrell:

Ray was extradited to the US to face trial. He replaced his first attorney, Arthur Hanes, with Percy Foreman. Foreman, who had represented more than 400 murder-case defendants, convinced Ray to plead guilty as the only way of avoiding the death penalty. On March 10, 1969, Ray pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. A “mini-trial” on that day settled few of the questions which had arisen during the preceding year. And Ray himself hinted at a conspiracy, interrupting the proceedings to saying that while he “agreed to all these stipulations,” he did not “exactly accept the theories of Mr. Clark” (the Attorney General)…”I mean on the conspiracy thing.” Three days later, Ray recanted his plea and requested a new trial in two letters to Judge Battle. The judge did not act upon these letters, and was found dead at his desk of a heart attack three weeks later, literally with Ray’s appeal under his body.”

From the first, there has been the suspicion that Ray had not acted alone, assuming that he was even the assassin and not a decoy.

“Since recanting his confession three days after giving it, James Earl Ray began claiming his innocence, saying that he did not know King was in Memphis and that his actions had for months been directed by a mysterious person named “Raoul.” Beyond Ray’s own possibly self-serving statements, though, there are several indications that there was more to the King murder than just Ray. Among these are Ray’s sophisticated use of aliases, evidence of framing including a second white Mustang at the assassination scene and the convenient “bundle” of evidence implicating Ray, and several indications that Ray was aided or directed at times. For instance, Ray purchased a Winchester rifle and had it equipped with a scope, and then almost immediately called back and exchanged the rifle the following day for a Remington .30-06, telling the salesman that his “brother” had told him the Winchester was unsuitable. Ray had rejected a .30-06 during his original purchase as too expensive.

Researcher Philip Melanson has written that Ray used aliases which matched actual people living in Montreal, and began using those aliases before he first arrived there during his pre-assassination travels: “four of the five aliases used by Ray in the nine months preceding the crime were real Canadians who lived in close proximity to each other.” These people – Eric S. Galt, Raymond George Sneyd, Paul E. Bridgeman – all lived within a couple of miles of each other in Toronto, and all looked very similar to Ray. Galt and Willard, another Toronto resident whose name Ray used, both had scars on the right side of their faces, as Ray did. Though Ray had used aliases throughout his criminal career, there is no evidence Ray had been to Toronto prior to fleeing there after the King murder, and no explanation for how he came to use these particular names.

Other oddities written about by researchers of the case include a second white Mustang, not owned by Ray, which may have been the one seen fleeing the murder scene, as well as the CB radio “hoax” mentioned earlier, and a delivery of an enveloped to Ray by a mysterious “fat man.” Some writers have interpreted the evidence as a sophisticated operation which brought Ray into an assassination plot and then left him holding the bag at the scene of King’s murder.

There was no eyewitness to the shooting, and there are credibility problems with the sole witness to Ray’s allegedly fleeing the roominghouse bathroom from which he is said to have fired the rifle. The slug removed from King’s body was never matched to Ray’s rifle. The rifle shot was never proven to have come from the bathroom window, and may have come from the bushy area on the ground below.

Ray’s skill with a rifle is dubious, and while he did commit armed robbery he had never harmed anyone previously during his criminal endeavors. And the man whose career one author described as “a record of bungled and ludicrously inept robberies and burglaries” purportedly managed to kill King with one perfect shot and then elude authorities for longer than any other American political assassin.

Further, reminiscent of Oswald and the JFK assassination, there appears to be no motive for Ray the loner to kill King. A petty criminal, Ray seems unlikely to have committed the crime purely out of racial hatred, and anecdotes of his racism are thin. The idea that he killed King in order to achieve notoriety is implausible given the lengths to which he went to avoid capture (nearly succeeding). As Ray’s brother John told the St. Louis Dispatch following James’ arrest: “If my brother did kill King he did it for a lot of money – he never did anything if it wasn’t for money.”

Skeptics point out that Ray’s story of Raoul has never been backed up by any solid evidence, and despite some minor mysteries, concrete and credible evidence tying Ray to any conspiracy has never emerged. The problem here is that the FBI, which conducted much of the initial investigations, was more interested in finding and then convicting Ray than in finding accomplices. The FBI had received death threats against King which it had never shared with the civil rights leader, and it withheld relevant files from later investigations. Beyond the FBI’s initial investigation, the only large-scale study of the King murder was undertaken by the House Select Committee on Assassinations. And that body found a “likelihood” of a conspiracy.”

maryferrell.org

A visionary figure, an icon to much of a generation, struck down at the height of his youth and power. Does this sound familiar, in the 1960’s? Yogi Berra, the beloved baseball star, might have said that we have “deja-vu all over again.”

AGAIN, THE LONE ASSASSIN

“Deja vu all over again.” Less than five years from the astounding events in Dallas, November, 1963.

In political killings it’s almost a cliché: a figure of great importance is gunned down by a miscellaneous nobody, someone who happened to hate the target’s politics, or just needed an outlet for their lunacy, so the story goes. Much historical evidence supports the pattern of sad, eccentric, hapless souls who achieve their one moment of fame in a lifetime by a murderous act. Usually, there’s no grand group of conspirators behind them. Does anyone really believe that John Hinkley, Jr. was used as the tool of Reagan’s political enemies? No, the troubled soul was driven by internal demons, not external ones.

At times, however, a trail leads from a lone, demented gunman to higher places. Was the King assassination one of those times? What in heaven’s name was James Earl Ray doing all the way to London when apprehended? He was the kind of yokel you’d expect to catch at the county line.

There aren’t quite the hundreds and hundreds of books on King’s assassination, as there were on Kennedy’s, nor as large an army of minutiae hunters sifting through thousands of scraps of evidence over endless decades. Nonetheless, the doubts and questions are real, and rise from logic. A guy with no particular track record of racism bound and determined to kill MLK? An uneducated prison escapee, in just the right place at the right time to achieve an incredibly accurate shot to fell King, then able to nearly flee the western hemisphere and melt into a foreign population? For many, it doesn’t pass the basic smell test. The aroma leaves the impression of at least a minor conspiracy, one or two people with resources helping the unsophisticated Ray be the decoy in Memphis, pull the trigger or at least participate in the plan, then fly away with his name in the news, deflecting attention from others. That may not be what happened, but there’s no obvious, faulty logic in floating the possibility.

Will we ever know what happened in the MLK assassination?

For the FBI the case was simple, straightforward, a closed case: Ray rented the room, was seen, rushed from the boarding house with a bundle wrapped in cloth, abandoned the bundle including the rifle, left fingerprints on the weapon that killed King, hurriedly fled the scene, that and the whole nine yards. Not exactly a puzzle to identify the assassin.

However, no one disputes that the behavior of the FBI toward King and his movement, throughout the 50’s and 60’s, was embarrassing by today’s standards (really any decent standards). Astonishing though it may be, J.E. Hoover even saw to it that King was threatened with exposure of his private picadillos, with the explicit suggestion that he commit suicide! No present historian doubts those facts: Hoover hated King and everything he stood for, and thus his agency acted execrably toward the civil rights hero. Obviously that could taint any federal investigation: it was to the interest of the FBI to construct an open and shut case, as low profile as the circumstances allowed. The lone nut assassin theme, true and tried and predictable, usually plays well with the public.

But is there much evidence that any guiding hand really helped James Earl Ray in cutting short the life of the Dreamer? What about the trials, hearings, and the later investigation by a congressional body?

TRIALS, CRIMINAL AND CIVIL

“Why, Martin’s Vietnam views alone were enough to get him murdered. Others have been shot for less.” Reverend Jesse Jackson, 1976

In 1977 and ’78, the House Select Committee on Assassinations officially reviewed not only the JFK assassination by Martin Luther King’s death five years later as well. Their conclusion: while finding no evidence of government conspiracy or involvement, they suspected one or more persons colluded in some fashion with James Earl Ray in the hit on King, providing plans or resources or means to a getaway.

In 1977 and ’78, the House Select Committee on Assassinations officially reviewed not only the JFK assassination by Martin Luther King’s death five years later as well. Their conclusion: while finding no evidence of government conspiracy or involvement, they suspected one or more persons colluded in some fashion with James Earl Ray in the hit on King, providing plans or resources or means to a getaway.

Thus when numerous authors explored King’s demise with a healthy skepticism, and a civil trial even expressly found for the King family and awarded damages for the acts of a supposed conspirator, the case for criminal activity above and beyond Ray stood on respectable ground, far above the vague ravings of tin-foil hat theorists.

“MLK’s Family Feels Vindicated

The widow of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. says she feels vindicated by a jury’s finding in December 1999 that her husband was the victim of a conspiracy, not a lone assassin, and says it is the duty of the Justice Department to look at the information presented in the Memphis case.

“I think that if people will look at the evidence that we have, it’s conclusive and I think the Justice Department has a responsibility to do what it feels is the right thing to do, the just thing to do,” Coretta Scott King, told CBS Early Show Anchor Bryant Gumbel a day after the trial.

The jury of six blacks and six whites deliberated only about three hours before returning the verdict in a civil lawsuit brought by the King family, reports CBS News Correspondent Jennifer Jones. They had sued Lloyd Jowers, a 73-year-old retired Memphis businessman who claimed six years ago that he paid someone other than James Earl Ray to kill King.

The Kings were awarded $100 in damages, but they weren’t after money. What they wanted was a verdict that would lend support to their call for a new investigation of the killing.”

CBS, 1999

(A $100 award for the loss of a life is it’s own anomaly, almost a joke, as we’ll discuss.)

Again, CBS:

Ray’s guilty plea was upheld eight times by state and federal courts. A U.S. House committee concluded in 1978 that Ray was the killer but he may have had help before or after the assassination. The comittee did not find any government involvement in the murder.

William Pepper with his friend Martin Luther King

“The jury also heard a great deal of evidence which exonerated James Earl Ray,” (Plaintiff’s Attorney) William Pepper said Thursday. “That should be made clear because there are spins coming out indicating that James was part of this conspiracy. That’s not what the jury found or heard. They heard strong evidence that James was an unknowing patsy.”

Jowers owned a small restaurant, Jim’s Grill, across the street from the Lorraine Motel, where King was killed. On the day of the murder, Ray, a prison escapee from Missouri, rented a room under an assumed name in a rooming house above Jim’s Grill.

In 1993, Jowers said on ABC-TV that he hired King’s killer as a favor to an underworld figure who was a friend. He did not identify the purported killer, but said it wasn’t Ray.

Jowers, who has never repeated the claim, was sick for much of the trial and did not testify.

Lewis Garrison, Jowers’ lawyer, told jurors they could reasonably conclude King was the victim of a conspiracy but said his client’s role was minor at best.

He said it was hard to believe that “the owner of a greasy spoon and an escaped convict” could have pulled off King’s assassination.”

Cbsnews.com,, December 8, 1999

After four weeks of testimony and over 70 witnesses in a civil trial in Memphis, Tennessee, twelve jurors reached a unanimous verdict on December 8, 1999 after about an hour of deliberations that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated as a result of a conspiracy. In a press statement held the following day in Atlanta, Mrs. Coretta Scott King welcomed the verdict, saying , “There is abundant evidence of a major high level conspiracy in the assassination of my husband, Martin Luther King, Jr. And the civil court’s unanimous verdict has validated our belief. I wholeheartedly applaud the verdict of the jury and I feel that justice has been well served in their deliberations. This verdict is not only a great victory for my family, but also a great victory for America. It is a great victory for truth itself. It is important to know that this was a SWIFT verdict, delivered after about an hour of jury deliberation. The jury was clearly convinced by the extensive evidence that was presented during the trial that, in addition to Mr. Jowers, the conspiracy of the Mafia, local, state and federal government agencies, were deeply involved in the assassination of my husband. The jury also affirmed overwhelming evidence that identified someone else, not James Earl Ray, as the shooter, and that Mr. Ray was set up to take the blame. I want to make it clear that my family has no interest in retribution. Instead, our sole concern has been that the full truth of the assassination has been revealed and adjudicated in a court of law… My husband once said, “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” To-day, almost 32 years after my husband and the father of my four children was assassinated, I feel that the jury’s verdict clearly affirms this principle. With this faith, we can begin the 21st century and the new millennium with a new spirit of hope and healing.”

From thekingcenter.org

But does the verdict in the civil trial really add up to much? Skeptics of that trial emphasize that the key “witness,” Lloyd Jowers, was not really a witness in this proceeding at all, pleading ill health and never showing up to say a single word. The assertion he made that he hired a hit-man to get King, at the behest of underworld connections, was never repeated under oath. Doubters point out that with the common phenomenon of false confessions, and the possible financial motivation related to the sensational claims, any Jowers-based conclusion of conspiracy should be taken with many grains of salt. The U.S. Department of Justice, for what it’s worth, gave no credibility to the narrative put forward by Jowers and others.

Nonetheless, a duly seated jury found for the King family, the plaintiffs in the case, finding that responsibility for MLK’s death not only reached beyond James Earl Ray but may have only involved him as stooge and patsy. That seemingly explosive verdict was surprisingly little covered by U.S. mainstream media, leading to further suspicion that, at every level, the fix was in. But did the case simply amount to the family engineering a proceeding to hear what they wanted to hear? Opinions differ. The respected search site Snopes.com opined that there was much less there than meets the eye in that civil proceeding, and responded to “conspiracy theorists” by concluding:

Snopes.com

From the Justice Department:

To explain our conclusion, we have summarized the trial evidence relating the purported conspiracies and analyzed that evidence in view of the results of our investigation and other relevant information that was not presented in King v. Jowers.

The DOJ authors give critical examples of what they consider merely wispy smoke, leading to no fire:

Most of the witnesses and writings offered to support the various government-directed conspiracy claims relied exclusively on secondhand and thirdhand hearsay and speculation. Additionally, none of these allegations were ever linked together. Rather, the hearsay evidence alleged that various government agencies participated in assorted assassination plots that are actually contradictory.

One allegation came from an acquaintance of Jowers who testified regarding a double hearsay account of an alleged conversation in a barbershop in which a supposed FBI agent remarked that the CIA was responsible for the assassination. Unrelated to this allegation, other hearsay evidence presented a different conspiracy, one to silence Ray after he pled guilty. One of Ray’s former attorneys related a double hearsay account from two deceased inmates suggesting that, ten years after the assassination, Ray was the target of a government-directed murder contract. A former government official further testified that he heard an unconfirmed rumor that FBI snipers were dispatched when Ray escaped from prison.”

xxxxxx

(Again, from the official DOJ Website:)

“James Smith, formerly a Memphis police officer, testified that he understood that Dr. King was under government surveillance during the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis in March 1968, two weeks before the assassination. Smith reported that he observed a van filled with radio equipment outside the Rivermont Hotel where Dr. King was staying. Smith said that he heard from unidentified sources that the occupants of the van were federal agents conducting electronic surveillance.

Eli Arkin, a former Memphis police intelligence officer, answered questions about the presence of military personnel in Memphis. Arkin testified, consistent with what he previously related to us, that in March or April 1968, Army intelligence agents worked in his office while he was gathering information about the sanitation strike. According to Arkin, the agents never explained what they were doing and merely observed and took notes.

Finally, Carthel Weeden, then the captain of Fire Station No. 2 across from the Lorraine, testified that on the morning of the assassination, two men who identified themselves as Army personnel said they wanted to conduct photographic surveillance. He reported that he showed them to the fire station’s roof. When we spoke to him after the trial, Weeden advised that, while he was sure he took military personnel to the roof, it was possible that he did so on a day before — not on the day of — the assassination. He also told us that he did not know how long the men remained on the roof.”

(Then, a section of the DOJ report that supposedly addresses the nitty-gritty of a government sponsored hit–once again second and third hand memories from assorted characters. Here they reference a deposition:)

The deposition provides details as to how the murder was allegedly accomplished. It states that on April 4, 1968, the deponent and others flew to Memphis from a secret airstrip owned by Marcello. Upon arrival, a woman from Belize, South America, now deceased, drove them to downtown Memphis and dropped off Raoul near Mulberry Street. Raoul then went into a building and left a bag outside. Afterwards, Raoul drove to New Orleans, picked up Ray in Atlanta, and flew with him to Canada. The deposition also alleges that after “the actual shooting of King took place [from] behind * * * a brushy little wall,” the woman from Belize “c[a]me around and pick[ed] up the shooter” in a Chevrolet Corvair. The shooter, along with the deponent, flew back to the Mafia airstrip and, while passing over the Mississippi River, threw the rifle into the river.

While the “John Doe” deposition presented the most detailed evidence alleging a government-directed conspiracy, no live witness testimony or documentary or physical evidence corroborated any part of its allegations. Conveniently, Doe remained unidentified for “security reasons” and virtually all of his alleged co-conspirators are supposedly dead. Moreover, many of Doe’s claims are contradicted by otherwise established facts. For example, none of the many witnesses at the Lorraine, nor the police who immediately responded, saw a woman drive by and pick up the shooter, and Ray never claimed that he flew to Canada with Raoul. Thus, this far-fetched, anonymous story has no indicia of reliability and is not credible. “

(Finally, regarding supposed military complicity:)

“The King v. Jowers trial included evidence relating allegations of United States military involvement in the assassination. Although no evidence specifically alleged that military personnel killed Dr. King, hearsay accounts and speculation suggested that military personnel were somehow connected to the assassination and actually witnessed it.

Dr. (William) Pepper introduced redacted copies of notes purporting to document interviews with unidentified military sources who claimed to have observed the assassination.(78) One set of notes records allegations by an unidentified source, claiming that he was one of two soldiers with the 902d Military Intelligence Group who was on the rooftop of Fire Station No. 2 conducting surveillance of Dr. King at the time of the assassination. This source reported that he observed and his partner photographed the assassination and “a white man with a rifle” on the ground leaving the scene. According to the notes, the source offered to approach his partner to attempt to obtain the alleged photographs for $2,000.

Another set of notes purported to document the allegations of a different unnamed source that he was one of two guardsmen with an Alabama National Guard unit, the 20th Special Forces Group (SFG), who was watching Dr. King and Ambassador Young from another rooftop near the Lorraine and observed the assassination. That source also claimed that his team coordinated with the Memphis police and someone he assumed to be with the CIA.

In a 1993 newspaper article from the Memphis Commercial Appeal, which was also introduced, reporter Stephen Tompkins asserts, without citing sources for the specific claims, that in the late 1960s, the 20th SFG conducted military intelligence surveillance of Dr. King and others from the civil rights movement. The article further provides that, on the day before the assassination, the 111th Military Intelligence Group (MIG) “shadowed [Dr. King’s] movements and monitored radio traffic from a sedan crammed with electronic equipment” and that “[e]ight Green Berets from an ‘Operation Detachment Alpha 184 Team’ were also in Memphis carrying out an unknown mission.”

Douglas Valentine, who authored a book about CIA intelligence operations during the Vietnam war, presented hearsay testimony from another unidentified source. He related that while writing his book, he learned that a single unnamed source allegedly involved in the military’s anti-war surveillance “heard a rumor” that the 111th MIG was conducting surveillance of Dr. King in Memphis on April 4, 1968, and took photographs of the assassination. Valentine advised us after the trial that he could not recall the identity of the person who told him the rumor but thought it was a former military enlisted man.

Another writer, Jack Terrell, who claimed to have worked with a CIA-directed group supplying arms and military software to the Contra rebels in Honduras in the 1980s, offered a hearsay opinion of a deceased source. Terrell testified that in the 1970s, as a private businessman, one of his employees, J.D. Hill, now deceased, claimed to have been with the 20th SFG in the 1960s. According to Terrell, Hill, who was a “strange person” with a drinking problem, expressed the “view” that in 1968 he had been trained specifically to participate in a military sniper mission to assassinate Dr. King that was canceled without explanation.”

Department of Justice