2001 Anthrax Attacks

Status of Mystery Investigation: Tentative Conclusions Reached 6/15/15

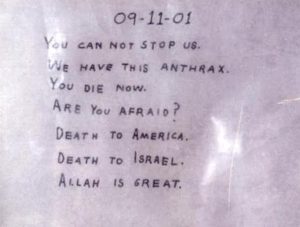

Not long after the national ultra-shock of September 11, 2001, and the demolished Twin Towers in New York, another terrorist scare transfixed the nation. First one person, and then finally five persons, almost many more, died from inhaling spores of the deadly bacteria Anthrax, dispersed deliberately through the U.S. mail system (in separate mailings in late September, and early October) to select Congressional and media addresses. As the envelopes were opened, white powder poured out, and panic set in.

An enclosed note staged a fundamentalist Islamic connection, echoing the jihad that had rocked the nation and its sense of security weeks earlier. A number of government officials assumed a foreign origin, perhaps a rogue middle-Eastern nation, such as Iraq. Indeed, evidence leading back to the Persian Gulf was welcome, support for the policy of war in the region.

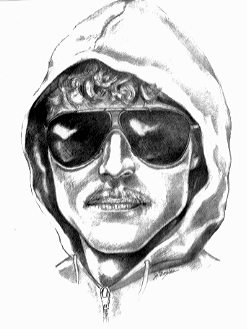

But the professionals at the FBI held firm, and worked from evidence, and profiling. Early on a psychological sketch of a “lone wolf,” perhaps disgruntled with his or her government employment as a bioscientist or with some huge axe to grind, emerged. The person was not likely to be openly confrontational, the profile speculated, but more the type to harbor a grudge for years, and strike back anonymously, when they chose.

The hunt for “the anthrax killer” was on, becoming one of the largest, most complex investigations ever conducted by law enforcement, anywhere in the world, in history. A search for a modern Jack the Ripper who used, not a dagger, but a bacteria much to small to see with the naked eye. Just as Jack the Ripper is no doubt dead, by now, the ultimate anthrax suspect died, of suicide, in 2008. We’ll never know for sure who the legendary London killer was.

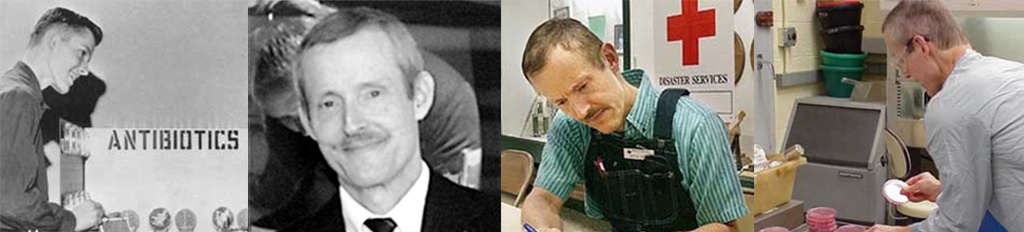

Dr. Bruce Ivins

Was the anthrax killer Dr. Bruce Ivins? Government prosecutors had prepared an elaborate case against him, though the highest levels at Justice would need to sign off on it to trigger the arrest and indictment. Before that could happen, he swallowed a brutal overdose of Tylenol, and died within a couple of days.

Case closed?

The crime, it’s tragic consequences, and the ensuing investigation stand as one of the most fascinating investigations in recent memory, with backstories wrapped within layers of other stories, with mysteries piled atop one another.

We offer links to a myriad of books, articles, and sites which illuminate what came to be called Amerithrax, and also our own tentative conclusions. (Rest assured when we offer even provisional conclusions, these are brief “executive summaries” based on more reading, research, and reflection than can be relayed without boring the reader, but we do cite numerous sources and avenues for data and perspective.)

As always, we remain open at MindOverMystery to adjusting our views, based on new evidence and perspectives.

The Weight of Evidence & Logic

Statistical probabilities point to the guilt of Dr. Bruce Ivins in the mailing of deadly anthrax spores in 2001. We at M.O. Mystery do believe that a preponderance of circumstantial evidence, all taken together, does yield a high probability that Dr. Ivins was guilty of mailing the lethal substance in September and October, 2001, sent to the offices of media and political figures. But the file is multi-layered, and sometimes confusing or contradictory, revealing one fascinating issue—psychological, scientific, forensic, legal, and moral—after another. The essential evidence against Ivins is said to be “circumstantial,” which it is, but quite compelling in our view.

It basically falls into three categories:

A) Background and Psychological Profile. Ivins had long revealed, to counselors and therapists, a complex, troubled, and even dark side to his personality. He was apparently aware that alongside the “good Bruce,” the cheerful, somewhat eccentric scientist who entertained at parties with his juggling skills, lurked a “bad Bruce,” just out of sight most of the time. Was it because his father had been an alcoholic, his mother a rare, near-homicidal case of temper who physically abused his father? Everyone’s family closet contains psychological skeletons, and stresses manifest in unpredictable ways. For the most part any tortured side to Ivins was kept below social radar all his life…but there were signs.

People walk by a brick office building 20 Nassau St., in Princeton, N.J., Monday, Aug. 4, 2008. A sorority, Kappa Kappa Gamma, has an office in this building. Former Army scientist Bruce Ivins, the top suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks was obsessed with a sorority that sat less than 100 yards away from a New Jersey mailbox where the toxin-laced letters were sent, authorities said Monday. (AP Photo/Mike Derer)

For example, the bad Bruce had developed a bizarre “obsession,” his own word, for the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority after being rejected by Kappa girl Nancy Haigwood many years before. On multiple occasions he drove hundreds of miles to stalk Kappa houses, sometimes breaking in surreptitiously, even armed, (a felony) and stealing their secret Codebooks. At one point he impersonated Haigwood, writing provocative letters about KKG under her name, for which she was blamed. He’d vandalized her car and home, spraying KKG around with paint. She was becoming a professional scientist in her own right, but her biggest scare in graduate school was when her lab notes—the whole key to her dissertation and professional degree—went missing. Anonymously a note told her what town mailbox (yes, a mailbox…) they’d been dropped in and they were recovered…Ivins admitted to the twisted act years later. Ivins developed obsessions with other women as well, e.g., his colleague Pat Fellows, his young assistant, Mara Linscott. When Linscott moved on and moved hours away he was crushed, plagued her with unwanted emails, drove long distances to give her small gifts but also, apparently, took poison for her along on one drive, torn as to whether to to use it.

Although Ivins reached late middle age with no criminal record, his many fixations and transgressions added up to bright red flags. (We’ve offered only a digest of representative incidents and examples here, obviously not every detail, which would involve a lengthy report.) The powerful conclusion is not simply that Ivins was much less balanced than most adults, sometimes “paranoid” or “delusional” in his later self-assessment, but the ways in which his peculiar nature was manifest dovetail with the person sought in the investigation. His particular history and behavior patterns offer a good match for an Anthrax mailer, and an early FBI profile outlines a person that fits him surprisingly well. He harbored jealousies and animosities, and found devious ways to get even. He had a history of sending illicit letters with false return addresses, from remote mailing locations. He was unfazed by the need to drive long distances, round trips that might take all night, to stroke his psychological agendas. He hinted that his surface mischief was only the visible tip of a much darker psyche. And in the “too-clever-by-half” stye of the bright and arrogant, he was convinced he could outwit those around him and carry out his fantasies unscathed.

Although Ivins reached late middle age with no criminal record, his many fixations and transgressions added up to bright red flags. (We’ve offered only a digest of representative incidents and examples here, obviously not every detail, which would involve a lengthy report.) The powerful conclusion is not simply that Ivins was much less balanced than most adults, sometimes “paranoid” or “delusional” in his later self-assessment, but the ways in which his peculiar nature was manifest dovetail with the person sought in the investigation. His particular history and behavior patterns offer a good match for an Anthrax mailer, and an early FBI profile outlines a person that fits him surprisingly well. He harbored jealousies and animosities, and found devious ways to get even. He had a history of sending illicit letters with false return addresses, from remote mailing locations. He was unfazed by the need to drive long distances, round trips that might take all night, to stroke his psychological agendas. He hinted that his surface mischief was only the visible tip of a much darker psyche. And in the “too-clever-by-half” stye of the bright and arrogant, he was convinced he could outwit those around him and carry out his fantasies unscathed.

B) Evidence of Means, Opportunity, and Connection in 2001

If the Background and Profile Section above point to the plausibility of Ivins as capable of the anthrax crime, then the question: what are the odds that someone of this profile would meet all of the following criteria at the time of the crime itself?

1) According to documents released by the FBI, and never challenged to the best of our knowledge, his private, evening hours in a bio-containment lab spiked just before both anthrax mailings. They had never, before or since, shown that pattern. He had no convincing explanation for the spike in hours. In simple street language, that’s just one hell of a coincidence.

2) Ivins had no alibi for the blocks of hours it would have taken him to have made the furtive drive to the mailbox on the edge of the Princeton campus in New Jersey. Most people would have some proof of whereabouts for large blocks of hours, but not Ivins. Remember, his history was one of such drives, and his wife led an almost separate life and had no clue.

3) The mailbox used as the drop was only a couple of hundred feet from an administrative office of the KKG sorority. The percentage of U.S. mailboxes right under the nose of KKG offices must be a small fraction of one percent. (NOTE: One detractor of the FBI mocks the KKG connection in New Jersey, observing that mailboxes not too far from KKG chapters would have been available to Ivins much closer to home, in Maryland or Delaware. But that misses the point: Ivins was crafty enough not to mail from quite close to home, and Princeton in the Trenton area would be just about right—far enough to direct attention away from his Ft. Detrick base, but within his known cruising range.)

4) The pre-stamped envelopes used had printing anomalies only found in envelopes sold in a few counties near Ivins’ home base. He maintained a mailbox at one such source.

5) The note in block lettering offered up phrases—i.e., “death to America, death to Israel” similar to what Ivins had used in other communications, such as emotional emails warning about the wave of terrorism.

6) The addressees of the mailings—media and political figures—were quite consistent with persons Ivins had mailed in the past with citizen opinions.

7) One of the contrived return addresses—”4th Grade, Greendale School”– echoed a memory Ivins would have had of an interaction with a grammar school of a similar name

8) The apparent use of bold letters as possible DNA ‘codes’ is consistent with Ivins’ history of mischievous play with codes.

Probability and Statistics

Another section of our Website discusses the under-utilized tool of statistical probability in the analysis of mysteries in greater detail. For our purposes here: The science of probability is simple, established math: what are the chances that the flip of your penny will come up ‘heads’ four successive times? .5x.5x.5x.5= .0625, or one-sixteenth of a chance of that occurring, simply 2x2x2x2=16. Less clear and more subjective is how to give values to unlikely events or clusters of “coincidental” events.

But let us stipulate that two of the facts above, the lab hours and the KKG proximity, seem so unlikely as make a 1/20 chance generously conservative, and assign a 1/5 chance to all other occurrences, also probably conservative, and the math would suggest: 20x5x20x5x5x5x5x5= an impressive 6,250,000 as the odds against all those things occurring by raw chance. Again, there’s no question that assigning those values has an element of subjectivity. If you disagree with our numbers, what odds would you place against each fact? Then use those in your multiplication. Note that even if you put the highly conservative, low value of a 1/3rd chance on all of these facts, the eight items would still multiply out to 6,561 as odds against. Most of us would have little more enthusiasm risking our lives on a one-of-six-thousand chance of survival than we would of one in the millions. With circumstantial evidence, it’s often the cumulative effect, or as prosecutor Rachel Lieber stressed repeatedly, it’s not so much one fact in this case as all the facts and circumstances, a large number of them, taken as a whole.

But let us stipulate that two of the facts above, the lab hours and the KKG proximity, seem so unlikely as make a 1/20 chance generously conservative, and assign a 1/5 chance to all other occurrences, also probably conservative, and the math would suggest: 20x5x20x5x5x5x5x5= an impressive 6,250,000 as the odds against all those things occurring by raw chance. Again, there’s no question that assigning those values has an element of subjectivity. If you disagree with our numbers, what odds would you place against each fact? Then use those in your multiplication. Note that even if you put the highly conservative, low value of a 1/3rd chance on all of these facts, the eight items would still multiply out to 6,561 as odds against. Most of us would have little more enthusiasm risking our lives on a one-of-six-thousand chance of survival than we would of one in the millions. With circumstantial evidence, it’s often the cumulative effect, or as prosecutor Rachel Lieber stressed repeatedly, it’s not so much one fact in this case as all the facts and circumstances, a large number of them, taken as a whole.

C) Neutral to Mildly Incriminating Circumstances

Those who challenge the government’s conclusion on the case often opine that yes, many a circumstance looked very bad for Ivins, but so many other factors just didn’t fit, and practically point to his innocence. We disagree with that interpretation. In our view, evidence or circumstances which do not fall into a highly incriminating category at least fall into a mildly incriminating, or at least neutral zone.

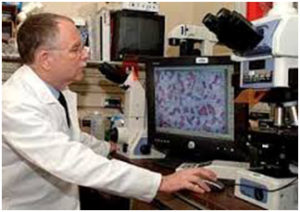

Take the matter of “the science,” primarily the origin of the spoors produced and slipped into the envelopes that made history. The FBI erred in overstating their scientific certainty, insisting that in Ivin’s repository of anthrax (infamous flask RMR-1029) they essentially had “the murder weapon.” The independent National Academy of Sciences review found that, simply put, it’s not certain where the anthrax came from, too many variables, too much sharing of samples over the years. This “undercuts the FBI’s case” breathlessly offered one national journalist, while a major contributor to the best documentary on Amerithrax concluded that “The foundation of the case is in jeopardy.”

No, not really. Let’s be crystal clear here—by no means did the National Academy find the microbial science exculpatory for Ivins. They found that their analysis might not live up to the high expectations for closure— “It’s very important for us to understand the limits of science in an investigation such as this,” concluded the NAS chair, Dr. Alice Gast.

In a culture where CSI-type programs fill our television airwaves we’ve come to expect a crisp scientific conclusion about a crime, and sometimes we get it, through a positive DNA match, for example. But sometimes the scientists can’t be sure, and we’re left with old-fashioned evidence, and critical thinking. The scientific evidence by no means pointed away from Ivins, it just didn’t nail him and button up the case. As the grandfather of the Ames-strain anthrax flask, as one of a small fraternity of ultra-knowledgable “anthrax whisperers” he was still a fully logical suspect to have been the producer of the airborne, breathable product.

Unanswered questions about precisely where and how he produced it? Yes. He had a lyophilizer—a drying machine—but the cumbersome thing sat outside his secure biolab area and would have been hard to use in the open. Other drying methods were available but not necessarily easy to execute in a small, private lab. Also, the extremely light, extremely floatable final product (especially of the second mailing) was hard to contain, likely to leak into areas surrounding it’s production, or be traceable to someone’s person or car. Or infect someone who worked in the same offices, which never happened. A thorough scouring of Ivin’s car and home and the like came up empty, but that was years after the fact.

Back at the time, however, he’d raised eyebrows for doing lots of disinfecting of his lab and office environments, without at first following protocols and informing supervisors. A friend and colleague, scolding him, told him that made him look god-awful, perhaps guilty of something. We put all this in the mildly incriminating category, and find it plausible that an anthrax expert of his calibre could have produced the spores and cleaned up after himself as he went, especially given the loose security and surveillance of USAMRIID, his workplace, at the time.

Taking all facts and perspectives together, we think the guilt of the late Bruce Ivins in the Amerithrax case is almost certain.

Skeptics & Backstories: The Many Falsely Accused

We believe, based on a broad palette of compelling circumstantial evidence, that authorities were very much on the right track in zeroing in on Dr. Bruce Ivins as the Anthrax Mailer, guilty of five homocides. Nonetheless a bevy of general skeptics and Ivins’ colleagues and supporters harbor doubts, and raise challenging questions.

True, those skeptical not only of government honesty but government competence can snidely say: “So, the seventh time was the charm? This was really it? But…why believe you this time?” They’d be referring to the fact that not less than six individuals were fingered for the crime before Ivins, not indicted, but leaned on heavily, publicly in many cases, with careers and even lives severely damaged. Early on (November of 2001) swarthy Middle Eastern-looking scientists, Irshad Sheikh and Asif Kazi, came under brutal scrutiny on little more than the thin suspicion of neighbors in the racial and cultural atmosphere that followed the Twin Towers horror of September 11.

The following year, one Major Perry Mikesell felt the heat—it’s said he collapsed under the stress and humiliation, finally drinking himself to death, while Lt. Colonel Philip Zack was named and felt persecuted for a time. In August of 2004, Dr. Kenneth Berry’s life and various homes were raided by some 50 agents in a deadly serious, coordinated strike. Apparently his sin was caring too intently about bio-hazards, and he did have financial incentive through his patent on a biological weapons sensor, but little else suggested him. He too was dropped as a suspect after tremendous damage to his reputation. And of course there was the odd persecution of Dr. Steven Hatfill beginning in 2002, aided by the careless journalism of a New York Times columnist, turning Hatfill’s life into a veritable nightmare.

The following year, one Major Perry Mikesell felt the heat—it’s said he collapsed under the stress and humiliation, finally drinking himself to death, while Lt. Colonel Philip Zack was named and felt persecuted for a time. In August of 2004, Dr. Kenneth Berry’s life and various homes were raided by some 50 agents in a deadly serious, coordinated strike. Apparently his sin was caring too intently about bio-hazards, and he did have financial incentive through his patent on a biological weapons sensor, but little else suggested him. He too was dropped as a suspect after tremendous damage to his reputation. And of course there was the odd persecution of Dr. Steven Hatfill beginning in 2002, aided by the careless journalism of a New York Times columnist, turning Hatfill’s life into a veritable nightmare.

He was hounded, figuratively, when the FBI employed the strategy of following his every move, openly, in an attempt to “break” him. Later literal bloodhounds were loosed on the case, supposedly reacting to something in Hatfill’s world, though precisely what was never clear. At the end of the day the FBI looked like a bully, an inept one at that. The government’s $5.8 million-dollar apology to Hatfill (finally in 2008) played in the media, making him the only false start with a high public profile, though he was one of many.

So after at least six “oops-never mind-wrong guy-carry on”- kind of experiences offered up by Federal investigators, skeptics are not without some grounds to wonder if the seventh person of extreme interest might have been just one more scapegoat.

So after at least six “oops-never mind-wrong guy-carry on”- kind of experiences offered up by Federal investigators, skeptics are not without some grounds to wonder if the seventh person of extreme interest might have been just one more scapegoat.

By all means, cases involving high stakes and public alarm have always been law enforcement-excess-waiting-to-happen. The pressure on the investigators in charge to produce results registers like the pressure that turns coal into diamonds, except that results are expected in weeks, not millennia. The chain of command doesn’t want to hear that the case is moving slowly, gingerly, taking great care not to step on anyone’s rights or jump to conclusions about any innocent citizens, no–command wants resolution. In this case, FBI director Bob Mueller was quizzed constantly by Bush and Cheney at the White House on progress finding the killer. The message may be unspoken but might as well be yelled from a rooftop-lets solve this, let’s prosecute someone!

On the positive side of high-profile cases, budgets and personnel are usually available generously, without question. At its peak, the Amerithrax investigation counted on at least a couple of dozen full-time investigators—it’s said a stunning 600,000 man-hours went into the case—and other resources as needed. Also, the limelight drives some precision in law enforcement science. The best and most experienced detectives draw the supervisory assignments. And knowing that opposing attorneys, and savvy court reporters, will one day focus a laser beam on every scrap of evidence, wise agents will employ the best techniques of the profession and document them carefully.

How all these variables played out in Amerithrax provides grist for eternal debate. Hatfill, Berry, the family of Mikesell and others will never be convinced that trashing their lives, on essentially no evidence, did anything to avenge the deaths of five innocents.

To look through the widest lens, however, we must remember that through the early years after the mailings, fear of further attack was a national companion. Imagine the public outcry if one of the suspects, or ‘persons of interest,’ had again dispersed bio-agents, with more resulting death, while agents had stayed at a polite distance, observing for months at a time. Then the outcry would be not FBI “harassment” and “overreach,” but bitter complaints of a feckless, toothless agency that let terror continue under its nose! Simply put, these scenarios can easily produce a no-win set of options for investigators.

The Bureau and DOJ needed a fresh suspect in Amerithrax, yes, but they didn’t create the sometimes destructive behavior patterns of Bruce Ivins, nor his patterns of shady testimony in numerous interviews with law enforcement. Years before anyone dreamed of an pressure-cooker Amerithrax investigation, Ivins had tossed his fellow scientist’s critical notes in a mailbox in his cruel prank, had written vindictive letters under false identities, had broken into sorority chapter homes, armed, to steal codebooks and make mischief, had even toted poison along on one of his obsessed drives with a thought to using it on a young woman. Government investigators could not have gone back and fabricated that sick history even if they’d wanted to! By all means the leap from these highly oddball, mad-scientist behaviors to Anthrax mailer is significant, but Ivins took the jump from a heightened precipice of mental illness, with violent tendencies. (How such a psychological profile slipped through the cracks to gain clearance to work with nature’s deadliest agents itself rises as a scandal within the story—we hope and assume the process has tightened in the wake of the Ivins case.)

Other anthrax handlers—the country easily had a couple of hundred—may not have all been paragons of perfect mental health, but another profile quite like Ivins’, shaped so distinctly towards potential Anthrax mailing, has not emerged and seems most unlikely.

At M.O. Mystery we believe that Ivins was a compelling suspect in the crime, most likely guilty, even if he was far from the first under law enforcement’s microscope.

The internet offers numerous links to different sources and commentators representing a host of different views, and conclusions.

The Inconvenient Matter of the Lie Detector Tests

In 2002, Bruce Ivins and a number of other Anthrax handlers were given thorough lie detector tests by either the Federal Bureau of Investigation or Department of Defense. He “passed,” part of the explanation of why he was not pursued earlier in the Amerithrax probe.

We have not been able to verify at this time if he took, and passed, a second polygraph some time later, as has been reported.

No lesser an Intelligence reporter than Jeff Stein of Newsweek and the Washington Post focused on the contradiction, for example in a column in early 2011 calling it “an inconvenient matter.” The Federal Bureau acknowledges the false pass of the test, but attributes it to “countermeasures” taken by Ivins. The topic of “countermeasures” alone is a long chapter in a book, if not another book itself.

We offer here a number of links and leads, and we at M.O.Mystery learned from this episode. There’s a whole organization flying under the Web Name “AntiPolygraph.org” Who knew? Google them, interesting stuff.

But our brief comments on this section can be summed up thus: the polygraph has always been an imperfect tool at best, even pseudo-science, which the late U.S. Senator Sam Ervin dismissed as “modern witchcraft.”

We have no doubt it can measure physiological responses, but emotions, much less “guilt” or “innocence?” No, not reliably. It can “sweat” many a suspect as did the witchcraft tools of old, but beyond that, hard to say. The despicable traitor Aldrich Ames passed his polygraph too, among countless other examples (hundreds, really) of meaningless results.

Prosecutors or defense lawyers have always invoked the results of a polygraph if it helped their case, dismissed it if it did not.

Therefore, we consider the polygraph overused and certainly over-cited in forensic matters. Whether Dr. Ivins “passed” or “failed” counts extremely little with our judgement and assessment. We think it’s high time for the polygraph to be, if not banned outright, then banished to the status of a very minor tool, of very limited importance.

THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT VS. THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT

This refers to the drama in which the civil lawyers of the US Department of Justice, as defense attorneys in a $50 million suit against the Department of Defense for negligence, attacks the case against Bruce Ivins as the Anthrax Mailer.

This was another episode which offered much glee to those who believe that the government does almost nothing right, and certainly nothing honest. The family of the first victim of inhalation Anthrax, Robert Stevens of Florida, filed a lawsuit against the government, based on the assumption that the lethal spores had originated at Ft. Detrick, Maryland, had been mailed by Bruce Ivins, and killed Stevens. The government, here the Department of Defense, had been negligent in letting those spores get away and be used in criminal conduct.

Enter the civil lawyers of the DOJ, who naturally draw the assignment of defending the U.S. government against lawsuits. Following normal lawyer behavior, they distanced themselves from any evidence that the anthrax had come from USAMRIID, from a government controlled location, and that the late Dr. Bruce Ivins had anything to do with it.

The only problem is that criminal division lawyers in their own agency had argued strenuously, only a few short years before, that the evidence against government-employee Ivins was absolutely overwhelming.

All this does nothing to improve the image of lawyers in general or the DOJ in particular, though we’re inclined to write it off as poor supervision of the Civil Division at the time. Some administrator should have been roundly fired for falling so very asleep at the switch! We have no information if someone was booted or not for the pathetic lapse in awareness.

Meanwhile, the powerful evidence against Ivins remains intact, even if the Civil Division of DOJ was tempted to disown it to try to defend their case.

A number of interesting articles on this chapter in the saga can be located, among others:

“The Justice Department has called into question a key pillar of the FBI’s case against Bruce Ivins, the Army scientist accused of mailing the anthrax-laced letters that killed five people and terrorized Congress a decade ago….Now, however, Justice Department lawyers have acknowledged in court papers that the sealed area in Ivins’ lab — the so-called hot suite — didn’t contain the equipment needed to turn liquid anthrax into the refined powder…”

BIOLABS AS A SUPERVISION DISASTER

As other sections of this report were being written, USAToday completed a May of 2015 study of the state-of-the-art of biolabs in this nation.

If their general conclusions are valid:

- Money is being thrown at bio-hazard research, but there are so many labs spread around that even supervising agencies don’t quite know where they all are!

- A number of dangerous incidents, or near-misses, have occurred that could have had lethal results, due to poor supervision or a lack of clear guidelines.

- The number of level 3 and 4 biolabs (designations for the highest levels of hazard, and theoretically most precaution in the protocols) continues to proliferate, especially level three, with little apparent end in sight and little apparent truly adequate oversight. In all a sobering, almost scary report.

Thinking back to Amerithrax, there’s more reason than ever to believe that Bruce Ivins, (or some other perpetrator for that matter) could have done extensive illicit work with deadly anthrax, and no one would have noticed.

Thinking back to Amerithrax, there’s more reason than ever to believe that Bruce Ivins, (or some other perpetrator for that matter) could have done extensive illicit work with deadly anthrax, and no one would have noticed.

AN ALTERNATIVE SCENARIO

The “Real” Story Behind the Amerithrax Mailings

We’ll never know if Bernard Egan’s primary motive was the promotions he kept not getting, for about 20 years now, as a biohazard researcher, or the fact that he really believed the U.S. was getting what it deserved when it messed around with the world. Had all those cracker-jack investigators looked back far enough they would have found it–he was awfully anti-American but it just didn’t stand out that much around Boston. He only majored in biology instead of something like sociology–reveling in the radical professors that were everywhere around–because he thought he could make a sure buck in science. Growing up to a poor single mom gave him a fear of poverty.

As he went on to grad school and decided to specialize in bio-hazards a friend had asked him, What’s the fascination with the smallpox virus, and bubonic plague, and anthrax bacteria? Isn’t it scary stuff to even be around?

Exciting stuff, he answered. You look through a microscope at something so tiny, and yet capable of wiping out life on the planet. Way beyond interesting, just really cool. Kind of a rush, really.

Well…o…kay….thought the friend, I guess everybody’s idea of a thrill is different.

When the dad who’d left him thirty-nine years before died, he willed him a small farm with half a dozen out-buildings in the Massachusetts countryside only fifty minutes away from the lab. Go figure. He and Gertie moved out there and enjoyed rural life well enough, all in all. With so many extra “barns” he could claim one as his chemical-hobby barn and just ask everyone else to stay away. Dangerous to even go in if you didn’t know what you’re doing, he would say. The few folks who ever ventured out to his neck of the woods were all too happy to comply and steer clear of the place.

Anthrax wasn’t just what he was working on back in Boston for a while, it was the most…fun, if that was the word. The thought that dormant spoors could sit for years or decades if conditions were right, and then jump to life and multiply and kill was kind of a delicious thought. To Bernie, anyway. Anthrax was neat stuff, you could mold it so many ways, kind of the silly-putty of the bio-hazard world. He got busy playing with it on his off-hours as well around 1996, when the flow of materials around the lab gave him the opportunity to sneak a nice sample home one day. Mostly with his own barn-lab hobby in mind, at first, he’d set up quite the little factory. Lots of surplus lab equipment can be scrounged up and repurposed, stuff too old to call any attention to itself. Among a couple dozen other handy gadgets, he even acquired some old centrifuges for drying spores in the future. It just seemed like producing powder would be really, really fascinating.

By late 1998 they’d dropped him from anthrax research–his favorite stuff!–because some genius who assigns priorities thought the field and its importance was fading. New smallpox experiments needed lots of research time, and he was reassigned. Idiots, thought Bernie. Sure, smallpox is one superb virus, deadly as a bomb in its way. We’ve also vaccinated it out of existence. What are these people thinking? When the clowns run the circus year after year, no wonder I don’t get to climb into the most exciting rings.

By late 2000, into early the following year, he was raising bacteria back on the farm like it was beef at a time of high steak prices. Plenty of it, the little bastards multiplied like micro-sized rabbits, if you knew how to grow them. He knew how to grow them.

And after some trial and error, how to dry them. It’s hard to explain the satisfaction. Creating a powder that makes talcum seem like crude gravel by comparison. White, light, sweet. Is baby’s behind a little chaffed.. well, come, come here now, I have some powder…

No, I’m not sick, he thought to himself, just thinking about making a point, a really big point, one day. These fools think anthrax isn’t much of a threat anymore? Are their IQ’s smaller than their shoe sizes, or what?

Everybody remembers where they were when the Twin Towers fell. Bernie was at work, a job getting a little boring these days, when terrorism went from being a word to a way of life. He didn’t snap, exactly, it’s just that everything fell into place, almost overnight. An aggressive country getting slapped back, big time, in his view. Government officials running around screaming about security on airplanes, as if that would ever happen again. Everybody doing a silly striptease in airports. Nobody’s busting into a cockpit again, you fools, but folks around the world might just ply a few of you with germs. How does half a million deaths strike you?

He’d bought some envelopes from a post-office his last trip down to see his mom, in Maryland, without even quite telling himself why. Pre-printed and stamped, you just put your letter in the mail. And its contents. No need to be licking or touching any stamps. Now was the time. Another thrust of public panic, and maybe the damned economic engine really would shut down and stop screwing over so many people. Would be easy to put the blame on “the terrorists,” on those guys with beards speaking the funny language and going on about Allah, and not have too much spotlight bounce back to the scientists. Go for it, he thought. They’ll take antibiotics after they open the letters, they’ll be fine, but they won’t laugh at anthrax research any more.

For his first mailing, he was a little leery of the ultra-light powder. Moving it from lab to envelope to his car to mailbox–it was runaway stuff. He settled for some coarser stuff from an old batch. Where to post it? Not around Boston. New Jersey seems far enough, and my sister still lives in Trenton, my cover for being there if I’m ever asked. Maybe it looks like some mad Princeton scientist mailing this stuff? No, they’ll be sure it was my Allah-loving guys. They’ll never think Boston. Are you kidding? And don’t look at me. I’ve been a virologist for several years now, working with smallpox.

But Bernie started to feel like a chicken, like those things his wife gathered fresh eggs from, within a few days. The light powder was the real deal, so what was he doing with that crude stuff? And it was hard to tell from early reports if anyone was getting the idea. And, sending to media people, what in hell was he thinking? The politicians are the ones that fund biohazard research. Talcum powder, Senator? Maybe which Senators didn’t matter too much. They would sure as hell bitch and moan if their offices were getting, shall we say, interesting mail.

Later, after investigators saw through the phony Islamic terrorist angle, after half a million man-hours were directed to finding just who did this, the Feds squinted nice and hard at every lab in the country. Not just a drive-by, but a real, in depth, getting-to-know-you and your personnel and… who had access to this stuff? Who precisely, name them all.

In the end they’d talk to him at least twice, but why should they bother with more? Sure, he knew anthrax well back in the day, but experiments with the wet stuff, and he never had a supply in his own office. Last few years he was on to other pathogens, more removed from anthrax growing than ever, it seemed. After a couple of conversations to cross him off the list, why waste more time on this guy? And if they had trooped on out to the country to see him in his natural habitat, well, he’d taken precautions. Cleaned up. And things like the centrifuges long since whisked away and in deep storage elsewhere. Yeah, I’ve got a barn-lab I fool around in. Care to see my hydroponic tomatoes?

Worries, for Bernie? Still a touch. There’s no statute of limitation on murder, and those humorless souls at Justice insist on calling it five counts. If it hadn’t been for the fact of that poor slob, Ivins, making himself such a perfect target.. And all those other rounds of suspects and lots of embarrassment.. The folks at Justice, and their FBI, were just so, so ready to nail Ivins to the cross and move on to some other crime and call this Case Closed.

If Ivin’s hadn’t stepped up and played the fool everyway but Tuesday? If they still needed their “killer?” He’d cleaned up in more ways than one, in case they came back with open notepads one more time. They weren’t all the brightest lights in the firmament. But those FBI guys could be tenacious, always ready to come back for another run at you. Come to think of it, they were a little like dried anthrax spores….Dormant. For now.

But fast forward to the year 2038 and Bernie and his wife are gone now, he deceased and she living in old age with a sister, and the farm’s been sold. And only after the death was confirmed as inhalation anthrax, and only after the source was traced to the new owner renovating that old structure, tearing it apart board by board releasing all kinds of dust up into his face, only after all that did it come together. A thin trace of the spoors, Ames strain, in the barn and around in the surrounding soil, but thin was still millions of spoors, lying in wait all these years. It was unmistakable, and a niece, young at the time, even remembered her surprise at Uncle Bernie visiting his sister, twice, full of conversation about everything unfolding in the aftermath of September 11th. He almost never came through Trenton, and now twice in a couple of weeks, while everyone was still in shock. A new generation of agents absorbed the evidence, and the more they gathered the more it fit like a snug leather glove. Damn. That Bruce Ivins guy, whom none of them had ever seen, must have just been the slob that looked good for the crime because they didn’t have anybody else. Unless he was teemed up with the other malcontent, Egan.

It often takes some time, some history, to reveal the next contour of a mystery, the next light emerging from a long shadow. And anthrax was the perfect thing to run through the history books, and finally bring you a surprise. Yes, anthrax.

It lies in wait a long time.

THE FUTURE OF THE STORY

DO BIOHAZZARDS HAVE A FUTURE?

It’s unlikely, though not impossible, that something or someone will burst on the scene one day and blow Amerithrax wide open again. Perhaps we’ll find out that someone, like our fictional Bernie from the previous section, got away with murder unnoticed.

Most likely the criminal case remains closed, with the perpetrator deceased in 2008. But what have we learned? What’s the future?

The unnerving revelations of Amerithrax are many: poor accountability for substances than could end millions of lives, unpredictable human behavior, substantial opportunity for future attacks launched by anyone with sufficient access and knowledge. Imagine microscopic anthrax spores emanating from the air circulation system of the Mall of America, or an office skyscraper, for days before detection. Tens or hundreds of thousands could fall ill, and most would die.

Amerithrax is easily set off to the side as an aberration, the work of a superficially cheerful Ted Kaczynski of the Biolab. But is the aberration just how few bio-attacks we’ve seen worldwide, when the weapons are so small, reproducible, deadly?

Amerithrax is easily set off to the side as an aberration, the work of a superficially cheerful Ted Kaczynski of the Biolab. But is the aberration just how few bio-attacks we’ve seen worldwide, when the weapons are so small, reproducible, deadly?

Unlikely we’ve seen the last or the worst of bio-terrorism. Either the lone, mad scientist or the organized terrorist can do stunning damage with these micro-weapons. There’s evidence that oversight of labs still leaves much to be desired. Our knowledge should tell us: those who fail to sufficiently study history, are doomed to repeat it.

Several books have been written about Amerithrax. Just not the last chapter.