We just finished an amazing one-two punch, or should I say a punch and counterpunch, of reading (one thousand plus pages). Kind of like getting blown out to sea by strong winds, and then aggressively pushed back to shore by powerful waves.

I’m talking about the Jeffrey MacDonald murders, now about half a century old, fading with each passing year. But an astounding case for anyone who makes the journey back in time.

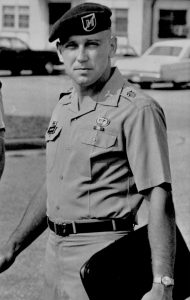

An army physician in Fort Bragg, North Carolina called for help in the middle of the night, having just survived an attack by crazed “hippies” in which his wife and daughters were killed, and he stabbed in the lower lung. But compared to his brutally slaughtered family, he was relatively unscathed.

This was in 1970, and so many of the principal actors are gone now. The army colonel who originally declared the charges against MacDonald without merit, as “untrue,” is long gone. Judge Franklin Dupree, who tried the case in Federal Court died in 1995. MacDonald’s chief defense counsel, deceased.

His best shot at a defense, the ever-confessing “hippy,” Helena Stoeckley, dead in her youth of cirrhosis and pneumonia. The grieving step-father, who couldn’t let the matter rest, died as has the actor who made him famous, Karl Malden. Jeffrey MacDonald’s loyal mother, gone too.

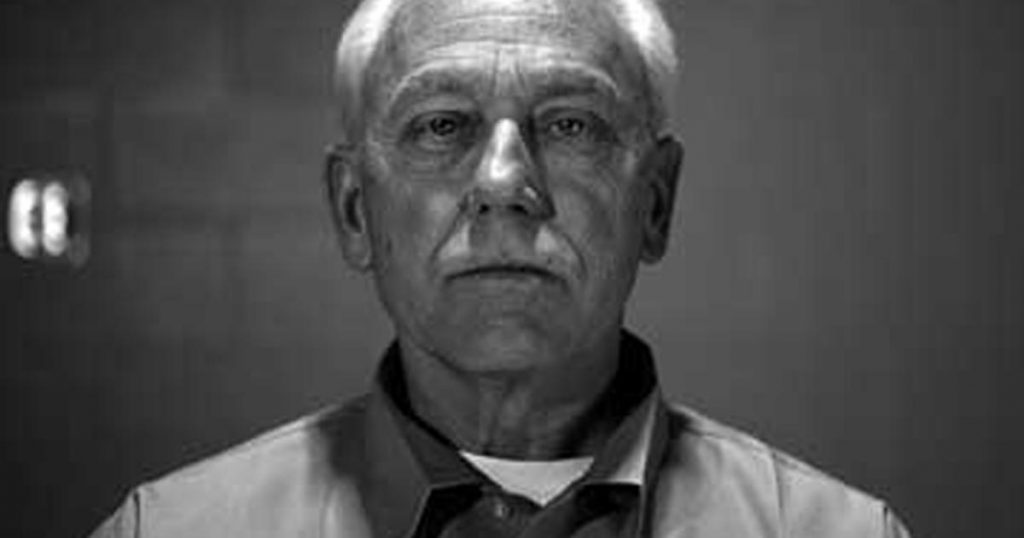

And MacDonald himself, once a dashing young Green Beret physician, iconically bright and successful and handsome, now in his seventies, in his fourth decade of wearing the orange suit in a metal cage, sadder and wiser and apparently doomed to die in prison, still protesting his innocence.

Why revisit this case, why care about it? Although the case was not overwhelming in sheer numbers of victims, not ignited by celebrity suspects, it was in it’s way the Crime of the Century. The human drama pushed to extremes– Charles Manson meets a Golden Boy, except that perhaps, like Jekyll and Hyde, they are one and the same.

And famous because of the drama of justice, and the wildly curved lenses of pubic perception. Job himself and his Biblical patience and pain on trial, helpless to do anything but watch events unfold in a personal horror film. Heroism on trial. Human limits on trial. Depravity on trial.

And famous because of the drama of justice, and the wildly curved lenses of pubic perception. Job himself and his Biblical patience and pain on trial, helpless to do anything but watch events unfold in a personal horror film. Heroism on trial. Human limits on trial. Depravity on trial.

Can goodness and evil exist so closely together in these extremes, can you open your freezer to find a fire inside?

The first punch is a revisit of Joe McGinnis’ “Fatal Vision,” the book made into a miniseries watched by sixty million Americans–read the book if you haven’t. At the end of the day, we see through the facade of Jeff MacDonald. With the author’s help, we see why the jury could have come to no other conclusion: MacDonald was some sort of psychopath, who snapped at least that one wretched night and butchered, by icepick and club, all he supposedly held dear.

By the end of the book, or the end of the film adaptation, the audience is there. Most of them. There was no way around the verdict. A triple murder, by MacDonald, it was.

But then the counterpunch. Errol Morris’s “A Wilderness of Error” pushes back at everything we knew, or though we knew, about the case. Yes, there were hairs, both real and synthetic, unaccounted for in the government theory. There were stacks of boxes of physical evidence, as complex cases always generate, but always under the government’s control, with grudging and limited access given to defense counsel. Some evidence appears to have been hidden from prying defense counsel eyes.

And most of all there was the question of fairness, of judicial balance in the case. Example: for whatever reason the prosecution wished to read long, rambling sections of the Charles Manson story in front of the jury, chapter and verse on cults and satanism and the like, and Judge Dupree allowed it.

But when the defense wanted to present six witnesses who could corroborate Helen Stoeckley’s many admissions of her presence at the crime scene, the judge was suddenly conservative about testimony that might inflame or prejudice or confuse a jury, and disallowed it. He seemed to have one standard for the state, another for the defense, and many attorneys who lean towards MacDonald’s guilt to this day will nonetheless assert that “he did not get a fair trial.”

In the end, a crime rests on a bed of physical evidence, and someone did, or did not, commit it. Courts adjudicate the world of fact, not of fiction, we’re told. But stepping into the world of these two accounts reminds us that in large part truth comes down to this: whose eyes do you see it through? Who has the podium, who’s telling the story?

The McGinnis and Morris narratives take us down the rabbit hole in opposite directions. Who’s telling the most truth? And how did MacDonald lose his family, now half a century ago?