Roanoke, The Lost Colony

You might call it the ultimate missing persons case.

Because it wasn’t just one person or two people, or an whole family that vanished. An entire colony of settlers, in effect a new, budding civilization, disappeared like a wisp of smoke.

It was the first attempt by the English to colonize the New World. In 1587 some 117 colonists, including several children, began a new life at the north end of Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina. They found the going rough and sent leader John White back to England to ask for further provisions, but due to European wars he could not return to look for them until 1590.

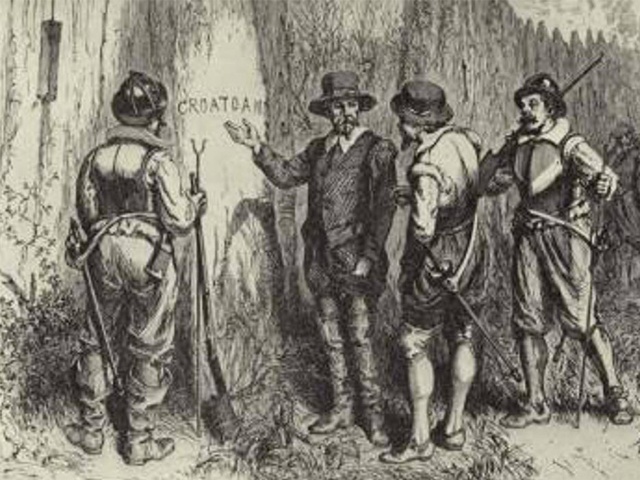

When he did, nothing. Just the name Croatoan carved into wood, and a disassembled village. And the beginning of a mystery that has confounded for over four hundred years. An award-winning play “The Lost Colony,” that runs each summer near the sight of the New World’s most famous disappearance. Dozens of books, and centuries of serious attention from everyone from amateur sleuths to emiment historians.

When he did, nothing. Just the name Croatoan carved into wood, and a disassembled village. And the beginning of a mystery that has confounded for over four hundred years. An award-winning play “The Lost Colony,” that runs each summer near the sight of the New World’s most famous disappearance. Dozens of books, and centuries of serious attention from everyone from amateur sleuths to emiment historians.

For lovers of true mystery, a perfect target–the whole package. The vanishing of over a hundred people with no trace, and large implications for history. Scant but tantalizing clues. Myth and legend filtering back from generations of native peoples, and Europeans. And new clues revealed, as if in a long but fascinating movie, as time goes by.

Join us as we contemplate the fate of the Colony at Roanoke, The Lost Colony.

PONDERING THE FOUR HUNDRED-YEAR OLD MYSTERY

Investigations into the fate of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke have continued over the centuries, but no one has come up with a satisfactory answer. “Croatoan” was the name of an island south of Roanoke that was home to a Native American tribe of the same name. Perhaps, then, the colonists were killed or abducted by Native Americans.Other hypotheses hold that they tried to sail back to England on their own and got lost at sea, that they met a bloody end at the hands of Spaniards who had marched up from Florida or that they moved further inland and were absorbed into a friendly tribe.In 2007, efforts began to collect and analyze DNA from local families to figure out if they’re related to the Roanoke settlers, local Native American tribes or both. Despite the lingering mystery, it seems there’s one thing to be thankful for: The lessons learned at Roanoke may have helped the next group of English settlers, who would found their own colony 17 years later just a short distance to the north, at Jamestown.

Investigations into the fate of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke have continued over the centuries, but no one has come up with a satisfactory answer. “Croatoan” was the name of an island south of Roanoke that was home to a Native American tribe of the same name. Perhaps, then, the colonists were killed or abducted by Native Americans.Other hypotheses hold that they tried to sail back to England on their own and got lost at sea, that they met a bloody end at the hands of Spaniards who had marched up from Florida or that they moved further inland and were absorbed into a friendly tribe.In 2007, efforts began to collect and analyze DNA from local families to figure out if they’re related to the Roanoke settlers, local Native American tribes or both. Despite the lingering mystery, it seems there’s one thing to be thankful for: The lessons learned at Roanoke may have helped the next group of English settlers, who would found their own colony 17 years later just a short distance to the north, at Jamestown.

History.com Oct. 2, 2012

Behind this bland recitation of the mystery lies a lot of opportunity for detective-like thinking, and narrowing down options. For example, seaworthy ships didn’t grow on the trees of the New World, food barely did. Yes, with severe drought conditions the settlers would have had a tough roe to hoe (literally and figuratively), thus a temptation to return to civilization as they knew it. But using what for transportation? These settlers would have known enough of the Atlantic voyage not to set out in rowboats…or so one would hope. Could they have built a truly seaworthy vessel? Well, perhaps, but that doesn’t seem all that likely.

Behind this bland recitation of the mystery lies a lot of opportunity for detective-like thinking, and narrowing down options. For example, seaworthy ships didn’t grow on the trees of the New World, food barely did. Yes, with severe drought conditions the settlers would have had a tough roe to hoe (literally and figuratively), thus a temptation to return to civilization as they knew it. But using what for transportation? These settlers would have known enough of the Atlantic voyage not to set out in rowboats…or so one would hope. Could they have built a truly seaworthy vessel? Well, perhaps, but that doesn’t seem all that likely.

But assimilation into exciting societies under starvation conditions makes some common sense. The DNA testing is promising, and we are searching for state-of-the-art results.

You might call this the ultimate “Ancestry.com” test.. Will turn out to be a large part of the answer?

ROANOKE…ENTER THE HISTORIANS WITH SHOVELS

Archaeologists bring more than than just digging tools to a project, of course. They bring a knowledge of how all the clues might fit into a giant, historical jigsaw puzzle. And by 2015 more work on that puzzle was coming together.

In 1998, archaeologists from East Carolina University stumbled upon a unique find from early British America: a 10-carat gold signet ring engraved with a lion or horse, believed to date to the 16th century.

The ring’s discovery prompted later excavations at the site led by Mark Horton, an archaeologist at Britain’s Bristol University… Recently, Horton’s team found a small piece of slate that seems to have been used as a writing tablet and part of the hilt of an iron rapier, a light sword similar to those used in England in the late 16th century, along with other artifacts… The slate…. bears a small letter “M” still barely visible in one corner; it was found alongside a lead pencil.

A gold signet ring excavated from the Cape Creek site on Hatteras Island, engraved with a prancing lion or horse, may have belonged to a prominent member of the Roanoke colony.

In addition to these intriguing objects, the Cape Creek site yielded an iron bar and a large copper ingot (or block), both… appear to date to the late 1500s. Native Americans lacked such metallurgical technology, so they are believed to be European in origin.

Horton told National Geographic that some of the artifacts his team found are trade items, but it appears that others may well have belonged to the Roanoke colonists themselves: “The evidence is that they assimilated with the Native Americans but kept their goods.”

Note that these particular Sherlocks need a range of skills–the scientific skills to uncover useful items and identify them, the historical knowledge to place them in context, and the deductive reasoning skills to eliminate certain possibilities while favoring others.

Note that these particular Sherlocks need a range of skills–the scientific skills to uncover useful items and identify them, the historical knowledge to place them in context, and the deductive reasoning skills to eliminate certain possibilities while favoring others.

It may be slow work, but can bear a lot of fruit in the end.

These finds, it would appear, lend weight to the thought that at least some of the settlers ended up in intimate association with the Natives already well established in the area.

NOT SO FAST… ARE WE SURE WHAT WE KNOW?

It seemed too good to be true. And it was.

Nearly 20 years ago, excavators digging on North Carolina’s remote Hatteras Island uncovered a worn ring emblazoned with a prancing lion. A local jeweler declared it gold—but it came to be seen as more than mere buried treasure when a British heraldry expert linked it to the Kendall family involved in the 1580s Roanoke voyages organized by Sir Walter Raleigh during Elizabeth I’s reign.

The 1998 discovery electrified archaeologists and historians. The artifact seemed a rare remnant of the first English attempt to settle the New World that might also shed light on what happened to 115 men, women, and children who settled the coast, only to vanish in what became known as the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

Now it turns out that researchers had it wrong from the start.

A team led by archaeologist Charles Ewen recently subjected the ring to a lab test at East Carolina University. The X-ray fluorescence device, shaped like a cross between a ray gun and a hair dryer, reveals an object’s precise elemental composition without destroying any part of it. Ewen was stunned when he saw the results.

“It’s all brass,” he said. “There’s no gold at all.”

North Carolina state conservator Erik Farrell, who conducted the analysis at an ECU facility, found high levels of copper in the ring, along with some zinc and traces of silver, lead, tin and nickel. The ratios, Farrell said, “are typical of brass” from early modern times. He found no evidence that the ring had gilding on its surface, throwing years of speculation and research into serious doubt.

“Everyone wants it to be something that a Lost Colonist dropped in the sand,” added Ewen. He said it is more likely that the ring was a common mass-produced item traded to Native Americans long after the failed settlement attempt.

Not all archaeologists agree, however, and the surprise results are sure to reignite the debate over the fate of the Lost Colony.

Smithsonian.com, April 7, 2017

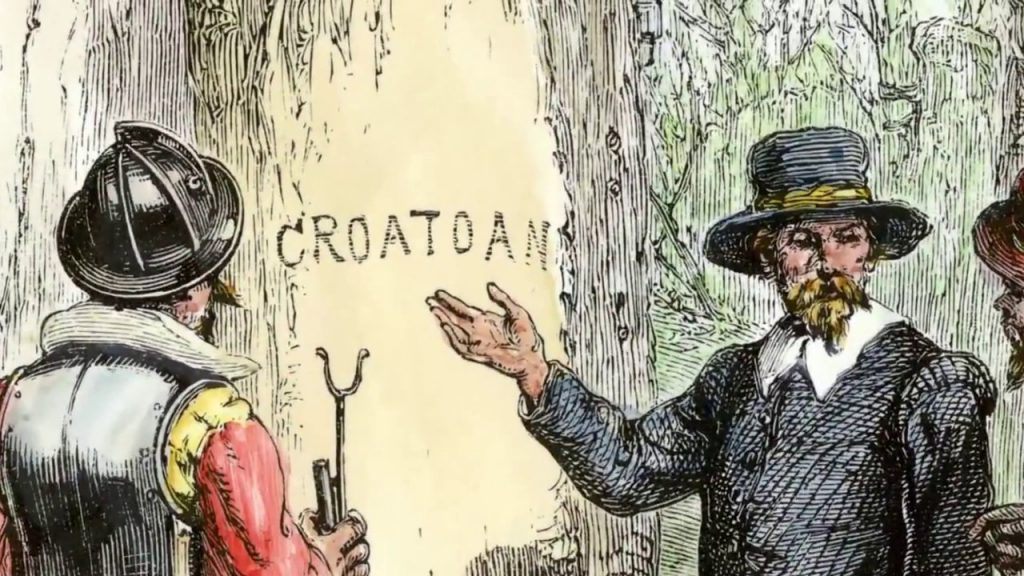

Were they slaughtered? This painting by White shows native North Americans dancing in a religious ceremony during an expedition in 1585. Many believe the ‘lost colony’ were massacre by American Indians

We include a fairly long excerpt here to illustrate: just when you think you’ve got it knocked, got a mystery wrapped up, some piece of evidence is called into question.

So you’ve got to keep an open mind.

But keep in mind, good mystery-solving scenarios are created from a broad number of facts, from the big picture. There exist already a plethora of items and indications pointing toward at least some settlers ending up living with Natives.

But what proportion? Will we ever have a firm idea?

HAVE WE CONSIDERED ALL THE POSSIBILITIES?

But a good mystery analyst is always…well… forming strong theories and then shooting them down. Yes, finding the holes in his or her own ideas.

We build houses of theory so easily. We allow fresh air into them so reluctantly, at times.

Take the matter of all the “evidence” that indicates assimilation of the settlers into neighboring Native cultures. It does qualify as substantial and scientific–telling artifacts, genetic clues pointing to intermarriage, and the like.

And it has a bit of logic behind it: settlers not yet adapted to survival in so new a world, starving during a severe drought, and needing the succor of established peoples, such as the Natives, quite badly.

But. What does all that really tell us, for sure? That there was genetic interaction between at least some colonists and some Natives, although precisely when, where, how many all remain unanswerable questions, at this point.

A small minority of these settlers might have swapped DNA with surrounding peoples. It might have been individuals, or a small break-away group who thought the Natives tolerable, while others settlers would rather die than “go Indian.”

Consider it: the possibilities in that regard are broad, and we have few tools for narrowing them down.

And the artifacts. Quite a few have been discovered that seem to solidly suggest European provenance, agreed. But how did they find their way miles from Roanoke, presumably in Native settlement areas?

And the artifacts. Quite a few have been discovered that seem to solidly suggest European provenance, agreed. But how did they find their way miles from Roanoke, presumably in Native settlement areas?

We don’t know. We really don’t. Those few settlers that we hypothesized going Native may have borne those items with them. Or, Natives visiting, or raiding the Roanoke settlement may have come away with the trinkets–the novel always seems worth taking and collecting, to many a culture.

So where does that leave us? With still quite a few questions that are unanswered, and perhaps can never be. We shouldn’t hesitate to offer a range of theories, as long as they’re plausible.

One short snippet of film floating around on the Internet caught our eye. The narrator reminded us that we really don’t know what John White encountered when he returned to the site three years after last seeing the settlers. We only know what he reported he found, a significant difference.

Remember that English official policy was driven toward exploration, colonizing new areas. Supposing White’s orders from home, either tacit or explicit, were to find a “successful” colony in full bloom, so that others would be motivated to sign on to the next such venture.

If he found the village collapsed and what’s more, skeletons lying all about, his temptation would have been to downplay the failure and carnage. It wasn’t possible to tell a story about a thriving, going concern and make it stick, but he might have suggested that folks took off for greener pastures inland. Evidence of anything more violent could have been ignored, or tossed out into the tides, never to be found by later explorers.

If he found the village collapsed and what’s more, skeletons lying all about, his temptation would have been to downplay the failure and carnage. It wasn’t possible to tell a story about a thriving, going concern and make it stick, but he might have suggested that folks took off for greener pastures inland. Evidence of anything more violent could have been ignored, or tossed out into the tides, never to be found by later explorers.

If you think we’ve traveled the road of sheer conjecture, you’re right, but don’t underestimate how much conjecture, with no real proof, attends all the other theories. We’re merely reminding Lost Colony analysts how often we swallow a basic story without asking, “was the original report correct?” We only know what White committed to writing, what historians have passed on.

White’s report did contain the references to Croatoan and the one partial carving, as if interrupted. If accurate, what do those clues mean? Again, we have room to construct scenarios. Was one carving only partial because someone ran out of patience, or because a deathly raid was in progress? We should keep our mind open to the possibilities, which are varied.

Remember, 115 persons, or 117 in many historical sources, made the trip that attempted a Roanoke settlement. We don’t know what happened, for sure, to even one of them, and certainly we don’t know what happened to all of them.

Now, please enjoy this documentary from “In Search of History: The Lost Colony of Roanoke:”