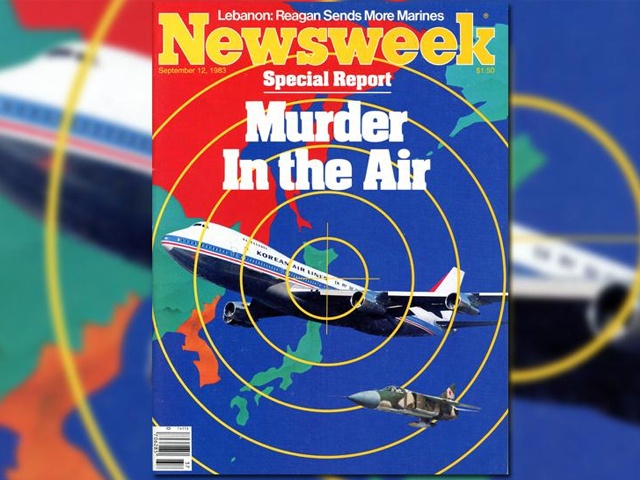

Korean Air 007

Everything about flight 007 was odd, the route, the communication, the whole works. It flew right over and through some of the most sensitive areas in all of the eastern Soviet Union. South Korea, and its ally the United States, maintain the violation of Soviet air space was an honest mistake, while the Russians, and numerous journalists worldwide, strongly disagreed.

What’s beyond dispute is that, after trailing the plane for some time, a Soviet fighter fired a missile, blowing it out of the sky and killing some 269 people. President Ronald Reagan called the destruction of the plane “a crime against humanity.”

With many of the key players on one side killed in the incident, key players on the other deep behind the Soviet “Iron Curtain,” and the shroud of top-secret intelligence activities over the whole matter, how will we ever know the truth?

We may not, but historical context, a thorough review of documents, and the critical thinking process may allow us to know the most plausible explanation.

The tragic end of Korean Air flight 007. Join us in a search for the truth.

AND A SCOLDING BY THE PRESIDENT

On that date, under Ronald Reagan’s watch, Korean Air Lines flight 007, bound from Anchorage to Seoul, South Korea, with 269 passengers and crew on board, strayed, significantly, into Soviet air space. After a number of minutes, and possibly clear warnings, a Soviet fighter launched the missle that shot it down. All lives were lost of course.

And the U.S expressed fury, of course. Reagan addressed international cameras with outrage at “the Korean Airline massacre,” asserting that “this crime against humanity must never be forgotten, here, or throughout the world.” While conceding that Russian airspace was overflown, he maintained that there was “no justification” whatever for the act.

For some, his eight-minute long harangue constituted adequate criticism for a deadly act. But for others, his obligatory condemnation of the act, without the followup of any clear sanction, was oddly limp. The ultimate cold warrior of the 1980’s stared hard at a Soviet travesty, and ultimately blinked and turned away, some felt.

The official explanation was a comedy of errors by the KAL flight crew, compounded by Soviet overreaction. Human fallibility being what it is, complex systems being what they are, we’re told we should expect a certain frequency of plain old human foul-up. For an explanation of strange events, look for a screw-up, not a set-up. Or as some Brits say, always go for “the cock-up theory of history over the conspiracy theory.”

What did happen to KAL007? A mind-boggling string of mistakes, rogue pilot action, planned testing of enemy systems?

You be the judge.

REASONS TO BELIEVE THE ACCIDENT THEORY

Not everyone thought Reagan’s reaction was too puny. The Association for Diplomatic Study and Training records the memories of ambassadorial personnel. Here, Paul M. Cleveland, a high-ranking U.S. diplomat in Seoul at the time, delivers another perspective:

The first days were consumed by general grief and concern. Dixie was at his best under such circumstances [Richard Louis “Dixie” Walker was the U.S. Ambassador to South Korea from 1981 to 1986].

Then began the difficult task of reconstructing events. We knew fairly early that Flight KAL 007 had gone down, but why and precisely where took time to discover. It was the Indication Center at Yongsan (a military intelligence unit) that began to put the pieces of information together.

From Northern Japan — a listening post — it had taped the conversation between the Soviet fighter pilots and their ground controllers. That gave us clear evidence of what had happened. The pilot had been ordered to shoot by a controller in Central Russia. I believe that the incident was not a deliberate provocation by anyone, but rather a Russian error in judgment — that is confusion about the nature of the plane that had wandered off course. The Soviets simply made a wrong decision to shoot it down, and I think the tapes proved that.

Paul M. Cleveland, The Association for Diplomatic Study and Training

How different from the perspective of angry hawks, who felt the President showed way too much restraint with the Soviets!

In “The Target is Destroyed,” the eminent American journalist Seymour Hersch weighs in with one of the book-length studies of the tragedy, and in the end he believes in the screw-up, the “cock-up” explanation. These full-length studies go into mind-bending levels of detail, but we’ll save you time by getting to the bottom line.

Hersch appears convinced by the official explanation: that although dozens of failsafes are built into navigational plans, radar tracking of planes, and ongoing communication with ground control stations, that all of these failed on the same day, for one reason and another. The pilot was unaware of his intrusion into Soviet airspace.

Hersch is such a venerable, decorated figure, respected by M.O. Mystery and the world of investigative journalism, that his endorsement alone gives reason to offer some weight to the screw-up scenario.

But in the end, which theory or theories pass the plausibility test?

For further perspective, read on.

REASONS TO BELIEVE THE ESPIONAGE THEORY

But little action followed. Reagan demanded an apology to the world and continued a number of sanctions — but he decided not to end grain sales to the USSR or to suspend arms control talks. George Will argued that “the administration is pathetic…. We didn’t elect a dictionary. We elected a President and it’s time for him to act.” The Manchester Union-Leader editorialized that “if someone had told us three years ago that the Russians could blow a civilian airliner out of the skies – and not face one whit of retaliation from a Ronald Reagan administration, we would have called that crazy. It is crazy. It is insane. It is exactly what happened.”

Washington Post, Andrew Rudalevige, July 18, 2014

We can only speculate, of course, what was said to Reagan by his most knowledgeable advisors. “Mr. President, this was only a sad comedy of errors. As near as we can determine, the pilots had navigation problems, they were probably trying to figure out why Soviet fighters were dogging them when the missile was fired. And those Russians, they’re touchy, maybe thought the plane was a fake passenger liner. They just overreacted.”

Or, the highly confidential briefing might have involved the CIA saying, “Mr. President, we’ve been gathering intel on Russian air defenses with the help of the South Koreans for years. Kind of sticking our toes in the water, then pretending we don’t know they were wet. Got away with it a few times. We miscalculated this time. We can’t admit it, but they shot down a plane, in their airspace, on an espionage mission.”

It’s a tragedy in either case. Nonetheless, Presidents have to take one posture in public, when they often know better in private. Who can read the Presidential tea leaves on this one? Possibly, the bluster that Reagan offered was obligatory, while his lack of real sanctions signified his knowledge of deliberate violation of Soviet airspace. Would Presidential archives reveal that truth? We doubt it. Those facts would be still be highly classified.

In summary points, the case for espionage-by-commercial flight is this:

*At this juncture in U.S.-Soviet defense and arms control negotiations, the U.S. and South Korea were keenly interested to know just how radar defenses were structured along the Eastern perimeter, especially around Kamchatka and Sakhalin Island.

*The CIA and the KCIA, literally the Korean CIA, were as close as Siamiese twins in intelligence collaboration, and a KAL flight was the logical choice to probe eastern Soviet air defenses.

*If you were to plan an espionage overflight, the route KAL007 took is a dead ringer, a perfect fit for the route that would trigger radar everywhere while leaving a manageable scramble back to international airspace in case of need. (Take note of the map-sketch of the flight in the previous section. What a perfectly crafted “accidental” route.)

*Speaking of stepping on the gas, the flight loaded extra fuel, while ditching some cargo in Anchorage. Flights don’t normally over-fuel–it adds weight and cost, but you carry extra fuel if you anticipate extraordinary events on the flight.

*Night flight was logical. If ultimately forced down, the pilot could claim navigational error, ill functioning radios and the like, and assert that at night he couldn’t see the various land masses he passed over. The intel on radar would be just as valuable at night.

*The pilot had jotted some navigational notes left back in Anchorage, notes that would make no sense unless he was plotting this extracurricular route into Soviet airspace.

*The pilot and crew were ultra-experienced, with ultra close ties to the Korean military. And in a pinch, other ranking pilots were flying deadhead, ready to help if needed.

*Supposedly, the number of on-board back-ups for navigational correction all, inexplicably, failed. So did all possible corrections from radar-based ground control, and all relevant communications with the ground. The number of failsafes that failed, taken all together, seem to defy staggering odds, certainly in the millions to one.

*At the end of a good, long, intelligence producing run the pilots were aware they’d finally been located in the sky and tracked by Soviet fighters. Our KAL pilot was headed for international airspace, only a minute or two away from it, when hit by a missile.

*Except for the 1978 KAL flight (discussed below) that pressed it’s luck by refusing to land over northern Russia, civilian airliners were not shot at, it just wasn’t done. The worst that happens is a forced landing, the obligatory indignation by crew that anyone could suspect ill intent, the obligatory scolding by the country trespassed upon. All passengers are flown home safe and sound. Those who planned this scheme accounted for a possible forced landing, the plane escorted down by fighters, but not on losing 269 people, a Congressman and families of diplomats included. (In bitter irony, Congressman Larry McDonald, a conservative Georgia Democrat, was on a foreign policy fact-finding mission to Seoul.)

*Naturally, the close, inner circle of Reagan foreign policy masters, and the few in South Korea who were read in, could never, ever admit to the planned spying. Can you even imagine the firestorm, the explosion of anger, at such a concession? In the U.S. context, impeachment, anyone?

*Note that in the end, the intel harvest was great for the U.S. and South Korea, and the Soviets looked bad, the nasty Soviet bear, in international context. Not a bad day in superpower gamesmanship, were it not for the tragic slaughter of all those passengers.

Numerous authors have written extensively about the specifics, the context of KAL007.

Is there precedent for the US, or intimate ally South Korea, “sticking toes in the water” to test Soviet perimeter defenses?

Oliver Clubb, author of “KAL007: The Hidden Story,” educates us on this. He relates how “on April 20, 1978, another KAL airliner…had ‘accidentally strayed’ deep into the other ‘top secret’ region…the area surrounding Murmansk in the Kola Peninsula.”

This plane, five hours out of Paris bound for Seoul, was heading northwest over the North Pole when it turned and headed south right into sensitive Soviet airspace. Innocent confusion? Clubb thinks that’s nearly impossible. Pilots aren’t navigational idiots, they know where the sun comes up, where it goes down, they know north from south.

For him, this was clearly one of the rare but occasional times that the West decided to trigger Soviet air defenses to assess them. Certainly, they could do that with the Air Force, but that’s too obvious, too close to tweaking armed conflict. With passenger planes, you can always claim error, put on the innocent face, and the consequences are minimal.

Until the disaster five years later.

In the 1978 case, scrambled interceptors were ignored, the international signals to land were ignored while the plane flew on with its presumed impunity. It took a strike that penetrated and depressurized the craft to encourage a landing, two lives were lost. A good deal of practical intelligence was gathered.

Clubb gives a long recitation of evidence that civilian airliners have at times been used–in a generally careful, measured way–by U.S. and South Korean and Israeli and Soviet intelligence, to sneak a peak at sensitive areas, perhaps even shoot quality photos from 30,000 feet. Everybody’s done it, everyone winks at it up to a point, his sources all say.

But the strongest points of his argument actually flow from what he considers the incredible unlikelihood, the overwhelming implausibility, of KAL007 flying the route they did, off course and often in Soviet airspace for over two hours, without having a clue of the mistake.

…….

In sum, the Reagan Administration’s explanation for how KAL Flight 007 happened to ‘stray off course’ and get shot down 2 1/2 hours later rest on a whole series of extremely implausible circumstances….the odds against all of these virtually inconceivable errors of commission and omission taking place as described are astronomical. The logical and factual absurdities in the Reagan Administration’s account suggest that we have been presented with a cover story.”

Oliver Clubb, “KAL007: The Hidden Story,” p.26-27, p.53

By no means is Clubb, a political science professor, alone in his assessment. From across the pond, R.W. Johnson of Oxford University wrote an incredibly detailed book–it’s like Cy Hersh’s work but, for this case, follows a path which much more closely tracks common logic. He, too, thinks that the odds against all the anomalies of the flight flowing from innocent mistakes are astronomical–theoretically possible, just as drawing to a Royal Straight Flush in poker, three consecutive hands, is possible as well.

He persuasively invokes Occam’s approach, and the deductive reasoning of Sherlock Holmes. Ironically, here you have what some would dub a “conspiracy theory” that also meets Occam’s criteria. The facts and logic fit this theory (espionage-mission-disguised-as-lost-passenger-plane) far better than any other, so why would you try to stretch and torture some other theory into place, to pound a square peg into a round hole?

We would give the “Occam award” to the clandestine surveillance mission theory, but others may well disagree.

What do you conclude, and what evidence and logic brings you to that conclusion?