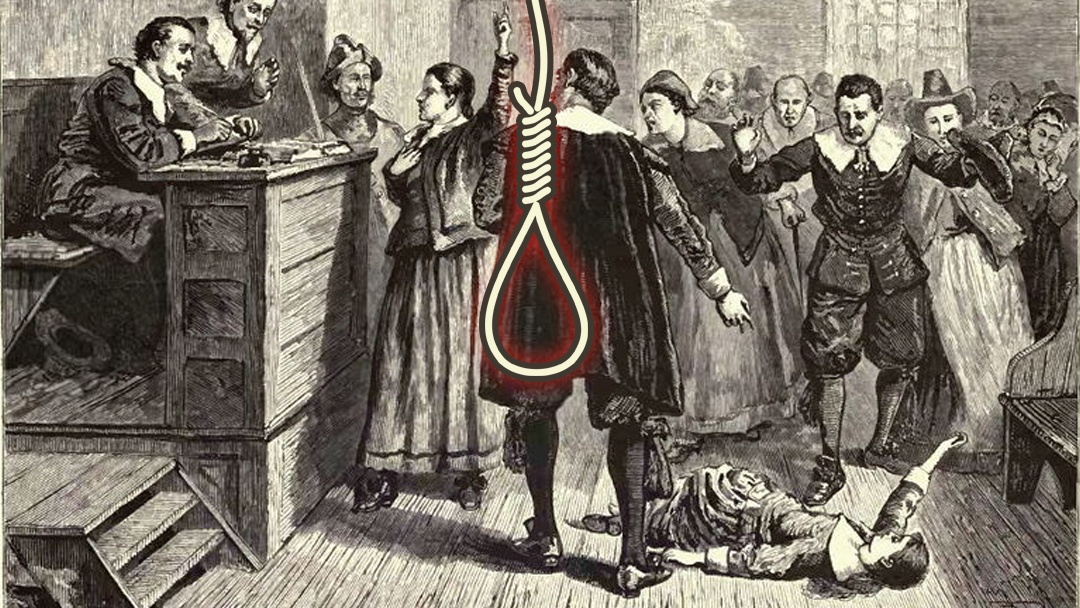

Contrary to popular belief, no witches were burned at the stake during the Salem Witch Trials. There were, however, hangings aplenty.

The infamous event was actually among the last witch executions, which had raged in Europe for over 300 years and took over 50,000 lives in the 16th and 17th centuries alone.

In 1662, a group of English Protestants, known as Puritans, settled in Salem Village, Massachusetts. Their strict and isolating religious faith provoked their fear of the supernatural, and as the hardships of colonial life intensified, they suspected the cause to be the work of the Devil. They believed evil forces wreaked havoc and harmed others through possessing humans, in other words, witches might be anywhere and everywhere.

In February 1692, amidst one of the coldest winters on record, the local minister’s nine-year-old daughter, Betty Parris, and 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams, began exhibiting strange behavior, for example flailing their limbs as they darted this way and that. When they didn’t improve, Reverend Samuel Parris called on the community doctor, who diagnosed them as suffering bewitchment under “an evil hand.”

Their symptoms of crawling skin, violent fits, and contorting their bodies spread to more girls through the town. Four of these “afflicted” girls blamed three local women, all considered outsiders by the community, of tormenting them.

Sarah Good, a pregnant beggar, Sarah Osborne, an elderly woman who had stopped attending church, and Tituba, a slave in Betty Parris’ home, were all faced with accusations of witchcraft.

There was no way for them to prove their innocence. They were pressured to either confess, seek forgiveness, and out other witches for their freedom – or to face death by public hanging.

Tituba denied guilt at first, but later confessed to harming the girls–forced by Good and Osborne to practice witchcraft on the Devil’s order. Sarah Osborn died in prison and Sarah Good was hanged shortly after giving birth in prison.

And so it went. Accusations, arrests, imprisonment, trials, and executions ensued, with little detailed investigation of the accusations, the accusers, or the accused.

By spring of 1693, there were nearly 200 people imprisoned, 14 women and 5 men hanged, and one 80-year-old man pressed to death by stones for refusing to confess. The paranoia ran so wild, at least two dogs were executed!

Many of these allegations came from young children and many of the trial jurors were relatives of the accusers. It wasn’t until the wife of Salem’s governor was targeted that the trials were finally suspended, and arrests came to a halt.

Four years later, the Salem community began to denounce the trials as a tragedy and court-ordered a day of contemplation and fasting for the colony. In 1681, the convicted were exonerated and restitution paid to their heirs. In 1931, the state of Massachusetts officially apologized for the events.

Still today, the reason for the “witchy” behavior remains unknown. One popular theory is that the accused suffered ergot-contamination, a fungus that may have infected the rye crop heavily used at the time. Poisoning can progress to swelling of the brain which causes irrational behavior, hallucinations, itching, spasms, and convulsions.

But even such a scientific hypothesis doesn’t explain why so many seemed “afflicted by the Devil” and so many did not, nor why the others were afflicted by their own madness, seeing the Devil under every rock, and in almost every person.

The Salem Trials remind us just how harmful the power of fear can be–and just how much we cannot predict about the behavior of human beings under stress.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-brief-history-of-the-salem-witch-trials-175162489/