Karen Silkwood

In the 1970’s, the promise of nuclear power was still king in the United States. And in Oklahoma, the Kerr-McGee corporation was king: the employer of thousands, respected, home-grown, bearing the name of the most powerful businessman-politician to ever come from the state, Robert Kerr. Among many other things the corporation was in the business of providing plutonium rods for the next generation of fast-breeder nuclear reactors.

It was however, an industry fraught with complication and danger. In this emerging technology, just what was safe? —after all plutonium 239 is, molecule for molecule, one of the more dangerous substances in industry. Even the first generation of nuclear plants alarmed the public. Before the 1970’s were over the reputation of nuclear power was rocked by the Three Mile Island meltdown in Pennsylvania, and the hard-hitting film The China Syndrome.

It was however, an industry fraught with complication and danger. In this emerging technology, just what was safe? —after all plutonium 239 is, molecule for molecule, one of the more dangerous substances in industry. Even the first generation of nuclear plants alarmed the public. Before the 1970’s were over the reputation of nuclear power was rocked by the Three Mile Island meltdown in Pennsylvania, and the hard-hitting film The China Syndrome.

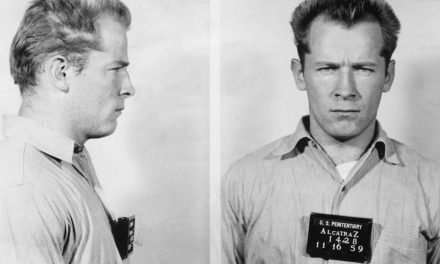

On this stage of great controversy enters a bright, assertive young employee of the Kerr-McGee plant in Crescent, Oklahoma named Karen Silkwood. A whiz at science and nobody’s fool, Karen was first viewed as a valuable employee among the underqualified local talent. But, she had too many opinions, too much interest in safety, too much interest in unions. Within a few years Karen had gone from promising new hire to thorn-in-the-side of management, her job barely protected by her union status. She made constant safety complaints, and speculated that significant quantities of plutonium were missing and unaccounted for. Perhaps unknown to the company, she was gathering copies of incriminating documents.

Her relationship with her employer darkened with each passing month. Then, in the fall of 1974, Karen was somehow exposed to alarming levels of plutonium, contamination that even spread throughout her home and personal belongings. Karen alleged carelessness at the company or even sabotage, while whispers accused her of contaminating herself to embarrass Kerr-McGee. Was Silkwood capable, in essence, of suicide to prove her point?

On the evening of November 13 Karen was driving Highway 74, toward Oklahoma City, on her way to meet New York Times reporter David Burnham and deliver her trove of documents, but never made it. Her Honda Civic was found off-road, smashed into a concrete culvert, and she dead of impact. The tow-truck driver remembers seeing papers at the scene, flapping in the breeze, but those papers disappeared that night. Karen’s documents were never seen again.

A regrettable accident—that was the official story—but friends of Karen, and enemies of nuclear power, joined forces to keep pressure on authorities. Her case became a cause-célèbre. The alternative investigation was slow: it seems that everyone supporting Silkwood, everyone who had information unflattering to Kerr-McGee, was intimidated by the corporation or by law enforcement. Even Mrs. Jean Jung, a woman who simply stated that she’d seen the sheaf of documents shortly before Karen’s last drive, found it prudent to move entirely out of state. Finally, in 1979 a civil verdict gave Silkwood a measure of vindication. Kerr-McGee was found responsible for her contamination by plutonium, due to negligence at the plant, and a jury awarded half a million dollars, plus ten million in punitive damages. Some years of legal wrangling later a sum of over a million was finally settled on, and transferred to her estate.

Yet, the mystery of the cause of Karen’s demise, and of what Kerr-McGee and law enforcement did behind the scenes before and after her death, has never been settled. An extensive trail of informal testimony suggests that Silkwood and her supporters had been illegally wiretapped and tape recorded for months before her death. Informal, because the judge at trial had decided that such testimony in open court would prove “inflammatory” to the jury, and disallowed it. But countless questions remain.

What can the evidence and logic tell us about the demise of Karen Silkwood? Join us in our quest for answers.

SOME BACKGROUND

In the evening of November 5, plutonium-239 was found on Karen Silkwood’s hands. Silkwood had been working in a glovebox in the metallography laboratory where she was grinding and polishing plutonium pellets that would be used in fuel rods. At 6:30 P.M., she decided to monitor herself for alpha activity with the detector that was mounted on the glove box. The right side of her body read 20,000 disintegrations per minute, or about 9 nanocuries, mostly on the right sleeve and shoulder of her coveralls. She was taken to the plant’s Health Physics Office where she was given a test called a “nasal swipe”. This test measures a person’s exposure to airborne plutonium, but might also measure plutonium that got on the person’s nose from their hands. The swipe showed an activity of 160 disintegrations per minute, a modest positive result.

The two gloves in the glovebox Silkwood had been using were replaced. Strangely, the gloves were found to have plutonium on the “outside” surfaces that were in contact with Silkwood’s hands; no leaks were found in the gloves. No plutonium was found on the surfaces in the room where she had been working and filter papers from the two air monitors in the room showed that there was no significant plutonium in the air. By 9:00 P.M., Silkwood’s cleanup had been completed, and as a precautionary measure, Silkwood was put on a program in which her total urine and feces were collected for five days for plutonium measurements. She returned to the laboratory and worked until 1:10 A.M., but did no further work in the glove boxes. As she left the plant, she monitored herself and found nothing.Silkwood arrived at work at 7:30 A.M. on November 6. She examined metallographic prints and performed paperwork for one hour, then monitored herself as she left the laboratory to attend a meeting. Although she had not worked at the glovebox that morning, the detector registered alpha activity on her hands. Health physics staff members found further activity on her right forearm and the right side of her neck and face, and proceeded to decontaminate her. At her request, a technician checked her locker and automobile with an alpha detector, but no activity was found.

On November 7, Silkwood reported to the Health Physics Office at about 7:50 in the morning with her bioassay kit containing four urine samples and one fecal sample. A nasal swipe was taken and significant levels of alpha activity (1,000 to 4,000 dpm on her hands, arm, chest, neck, and right ear). A preliminary examination of her bioassay samples showed extremely high levels of activity (30,000 to 40,000 counts per minute in the fecal sample). Her locker and automobile were checked again, and essentially no alpha activity was found.

Following her cleanup, the Kerr-McGee health physicists accompanied her to her apartment, which she shared with another laboratory analyst, Sherri Ellis. The apartment was surveyed. Significant levels of activity were found in the bathroom and kitchen, and lower levels of activity were found in other rooms. In the bathroom, 100,000 dpm were found on the toilet seat, 40,000 dpm on the floor mat, and 20,000 dpm on the floor. In the kitchen, they found 400,000 dpm on a package of bologna and cheese in the refrigerator, 20,000 dpm on the cabinet top, 20,000 dpm on the floor, 25,000 dpm on the stove sides, and 6,000 dpm on a package of chicken. In the bedroom, between 500 and 1000 dpm were detected on the pillow cases and between 500 and 2,000 dpm on the bed sheets. However, the AEC estimated that the total amount of plutonium in Silkwood’s apartment was no more than 300 micrograms. No plutonium was found outside the apartment. Ellis was found to have two areas of low level activity on her, so Silkwood and Ellis returned to the plant where Ellis was cleaned up.

When asked how the alpha activity got into her apartment, Silkwood said that when she produced a urine sample that morning, she had spilled some for the urine. She wiped off the container and the bathroom floor with tissue and disposed of the tissue in the commode. Furthermore, she had taken a package of bologna from the refrigerator, intending to make a sandwich for her lunch, but then carried the bologna into the bathroom and laid it on the closed toilet seat. She remembered that she had part of her lunch from November 5 in the refrigerator at work and decided not to make the sandwich, so returned the bologna to the refrigerator. Between October 22 and November 6, high levels of activity had been found in four of the urine samples that Silkwood had collected at home (33,000 to 1,600,000 dpm), whereas those that were collected at the Kerr-McGee plant or Los Alamos contained very small amounts of plutonium if any at all.

The amount of plutonium at Silkwood’s apartment raised concern. Therefore, Kerr-McGee arranged for Silkwood, Ellis, and Silkwood’s boyfriend, Drew Stephens, who had spent time at their apartment, to go to Los Alamos for testing. On Monday, November 11, the trio met with Dr. George Voelz, the leader of the Laboratory Health Division. He explained that all of their urine and feces would be collected and that several whole body and lung counts would be taken. They would also be monitored for external activity.

The next day, Dr. Voelz informed Ellis and Stephens that their tests showed a small but insignificant amount of plutonium in their bodies. Silkwood, on the other hand, had 0.34 nanocuries of americicium-241 (a gamma-emitting daughter of plutonium-241) in her lungs. Based on the amount of americium, Dr. Voelz estimated that Silkwood had about 6 or 7 nanocuries of plutonium-239 in her lungs, or less than half the maximum permissible lung burden (16 nanocuries) for workers. Dr. Voelz reassured Silkwood that, based upon his experience with workers that had much larger amounts of plutonium in their bodies, she should not be concerned about developing cancer or dying from radiation poisoning. Silkwood wondered whether the plutonium would affect her ability to have children or cause her children to be deformed. Dr. Voelz reassured her that she could have normal children.

pbs.org, first published Nov. 23rd, 1995

We start with such a long excerpt from public broadcasting to demonstrate just how much detailed science lies at the core of this very human, dramatic story.

Just what exactly did happen when Karen, rather suddenly, spiked positive for plutonium contamination?

She was a “troublemaker” of sorts, as even a daughter later asserted, but the theory that she contaminated herself for the scandal value is a bit of a stretch.

- It seems unlikely, for several reasons, that she was the author of her own contamination:

Even before the ultimate scientific-medical assessment at Los Alamos, Karen would have known of the danger of plutonium. There’s no evidence she was self-destructive or suicidal in that sense. - She had other, bigger fish to fry about that time. She wanted access to the plant for her clandestine search for falsified records about faulty fuel rods, for information about pounds of missing plutonium. She knew that testing positive for plutonium would stymie all that–she’d be very painfully scrubbed, sent home for long stretches, and likely watched more closely when back at the facility. All of which would make her main agenda, gathering hard info on irregularities at the plant, more difficult if not impossible.

- Some of the material was even found to be from parts of the secure facility to which she had no access. In all, evidence and logic point elsewhere for the source of the plutonium.

Was her poisoning accidental or staged, pure malicious sabotage? Plausible theories could accommodate either possibility, or a combination of the two:

- Even scientific Karen was unaware of the full scope of radiation danger before her journey to see the experts at Los Alamos, and the other employees were far less savvy. Some may have thought that slinging plutonium carelessly, or deliberately in the direction of a troublemaker, was great fun.

- Most line employees in economically depressed rural Oklahoma survived paycheck-to-paycheck, and wouldn’t have been much amused by threats to their livelihood. They might have dreamed up ways to sabotage Karen, or just as likely have been egged on by management, who increasingly (and rightfully) viewed Karen as a threat to the whole enterprise.

- Over time evidence emerged that Kerr-McGee management was capable of very aggressive action. For example,

credible witnesses alleged that management had contracted with professional spooks–folks who would surveil Karen’s activities for management, yet offer some deniability later as separate entities.

The notorious traffic “accident” that ended Karen’s life shortly thereafter has to be seen in the context of the plutonium scare, which certainly gave the appearance, at least, that nefarious forces were at work.

OTHER PERSPECTIVES

Quaaludes were found both in her car and in her bloodstream, and the Oklahoma State Troopers ruled that she had fallen asleep at the wheel. But her family and supporters noted there were skid marks in the road – how could she have hit the brakes while asleep? Dents and paint scrapes on her rear bumper lead her supporters to believe that she was deliberately forced off the road by a trailing vehicle. The documents she’d planned to share with New York Times reporter were never found.

The publicity surrounding the case led to a federal investigation of the plant, where many of Silkwood’s allegations were proven true. Kerr-McGee closed Cimarron in 1975.

Silkwood’s father and children filed suit against the company, not for wrongful death, but for willful negligence leading to her plutonium contamination. According to the book The Killing of Karen Silkwood by Richard Raschke, the family’s lawyers were harassed, intimidated and even physically assaulted. A key witness committed suicide before her scheduled testimony. The jury, nonetheless, found in their favor, awarding the family $10.5 million. On appeal, the amount was reduced to a mere $5,000 – to cover the destruction of Karen’s personal belongings during the decontamination of her apartment. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the case and it was headed for retrial when Kerr-McGee settled out of court for $1.38 million. They admitted no wrongdoing as part of the settlement.

Did Karen Silkwood deliberately contaminate herself? Or did she come into contact with plutonium because of lax safety standards at the plant? Or, most disturbing of all, did someone deliberately dose her with plutonium-239 as a way to shut her up? Did she drive off the road, or was she forced off?

Karen Silkwood’s story was popularized in the 1983 Academy Award-nominated film Silkwood, and in the years since she has become somewhat of a martyr for unionists, whistleblowers and those opposed to nuclear power. Others see her as shiftless, hard-living malcontent who was only looking for attention. Even her own children seem divided on her motives. Her son Michael told People magazine in 1999, “I am proud of Mom. Whether she did it to become the kind of legend that she became is not really important.” Meanwhile, her daughter Dawn said, “My belief is that she did what she did because she was a troublemaker. I don’t believe her intentions were as good as everybody said.”

Legacy.com, Nov. 13, 2016

As you absorb one take on the story, it’s important to remember the other perspectives.

There’s the tale of Karen who abandoned her kids for new adventures (or as the only way out of an impossible marriage), who raised hell when she wasn’t doing science, who smoked pot and was found dead with Quaaludes in her system.

All of that’s true, and paints a picture of a complex person, perhaps the troublemaker her daughter referred to.

But even a backstory can have a backstory. It’s important to note–if you think it even matters–that Quaaludes found their way into her life through a doctor’s prescription. Karen had a fiery and independent personality, but no more so than millions of other bright and activist individuals.

Things at Kerr-McGee were becoming darker, and more complex, all the time. How would you have behaved, on the inside of union activities and scientific activities at the plant, aware of what Karen was. It’s a question we should all ask ourselves.

Would we steal documents from a nuclear plant, in violation of federal law, to further a whistle-blowing agenda? What are the options?

- Break no laws and steal no materials, but quit one’s job and make public allegations, allegations likely to be dismissed as “baseless, groundless, not supported by any evidence.”

- Stay on the job and with the union, quietly talking with management and hoping for change.

- Quietly leave the job, warn close friends that the workplace isn’t safe, and just hope for the best. Hope that forty-pounds of missing plutonium doesn’t become a rogue state’s nuclear bomb, hope that small-cracks in fuel rods don’t become a meltdown that contaminates tens of thousands of people one day.

I’m not sure if I would take one of these options, or the path Karen chose. Are you?

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED?

Interestingly, there’s as much evidence about the demise of many a whistleblower as there is about Karen Silkwood, but the story usually leans toward “accidental death,” and perhaps a nod to “conspiracy theories.” The very phrase suggests that perhaps we ought not to take them all too seriously.

But for some reason, a mystery in itself in some ways, Silkwood’s story plays differently. It produces the assumption, in most people, that she met foul play on her way to meet that New York Times reporter. They’re aware that she carried a packet of (supposedly) very sensitive papers, disappeared, gone like smoke on the night of her death.

As MindOverMystery has probed a good number of whistleblower-based tragedies, certain patterns have emerged.

In a surprising number of cases, a packet or sachel or briefcase full of documents was known to be in a whistleblowers’ possession, but then, as some calamity struck, disappear as if into the ether. Never to be seen again.

That was case with Nebraska state investigator Gary Caradori, on the trail of high-level political prey, and with journalist Danny Casolaro, and with dozens of others you may or may not have heard of. At MOM we started a file on cases in which missing evidence was at least a significant part of the picture, and…you guessed it. We were able to think of a couple dozen such mysteries without even breaking a mental sweat.

And why should that surprise us, why should we expect otherwise? People with something to hide apply their common sense, which tells them: eliminate any incriminating documents, per se, and you’re halfway home to riding out this scandal. Without the documentation, those making your life miserable can much more easily be dismissed as overheated, even delusional do-gooders who don’t really know what they’re talking about.

So get rid of the smoking guns!

Getting back to the Silkwood story, it’s commonly reported and believed that Karen had a pretty healthy stash of documents to pass on to her reporter that night in November of 1974. One of the books on her saga even relates the story of a mild, ordinary middle-aged woman who saw Karen not long before she took her last drive. The lady was not political or involved in the whole scandal but was sure of one thing, Karen had a fat envelope of papers with her that night.

At first, after Karen’s death, the woman didn’t hesitate to simply affirm that she’d seen papers. But before long that lady found it prudent to move entirely out of state, so hot was the issue of what had happened, and so clear that Kerr-McGee was wanting to play hardball.

Even the existence of documents, not even their content, had become a red-hot potato!

Some of our closing thoughts:

We’re wryly reminded of the guys who robbed a small bank in a popular film, only to find out they’d made off with mob money in the process of being laundered. With fear in his eyes, one of them wondered if they could just explain to the mob that it had been “coincidence.” “No good,” another said. “Those guys don’t believe in coincidence.”

Here at MOMystery we’re a little more willing to believe in coincidence, but believing Karen died by pure accident the very night she was about the blow the lid off— that seems like an unlikely coincidence, to say the least. It’s possible one entity was sent to scare her off the road and it got out of hand, and that the documents disappeared through different means.

The tow-truck driver recalls seeing papers with the Kerr-McGee letterhead flapping around, but they were never seen after that.

What the corporation didn’t count on was a society growing as fiesty as Karen herself, full of private investigators and anti-nuclear activists and the like. Karen violated the law in carrying documents from the plant, but she wasn’t alone in acting illegally.

Had it not been for a very conservative judge, in fact, it would have been established in open court that the company was spying on Karen, and probably on other employees, in violation of the law themselves. The judge disallowed such testimony on the grounds that it would be “inflammatory.” Well, yes, perhaps. But isn’t it also material, in a trial that seeks to establish Kerr-McGee’s responsibility for the death?

In all, a stain on the reputation of corporate America, for which Karen paid the ultimate price.

That’s our take, what’s yours?